Three things irk me about “disruption” as it’s used in technology:

- New products that do what existing products do, but (theoretically) better, are not disruptive. They are “sustaining.” Instagram Video is not disrupting Vine. It’s competing with it.

-

The misplaced obsession with low-end disruption, which, as I argued last week, doesn’t apply nearly as strongly to consumer markets.

-

The characterization of obsoletive technology as disruptive.

There’s no better example of point number three than phones.

In my article, What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong, I included Christensen’s prediction that the iPhone would not be a success:

The iPhone is a sustaining technology relative to Nokia. In other words, Apple is leaping ahead on the sustaining curve [by building a better phone]. But the prediction of the theory would be that Apple won’t succeed with the iPhone. They’ve launched an innovation that the existing players in the industry are heavily motivated to beat: It’s not [truly] disruptive. History speaks pretty loudly on that, that the probability of success is going to be limited.

I regret the inclusion in last week’s article; I was making a rhetorical point that Christensen is consistently wrong about Apple, but this detracted from my overall thesis, specifically, that the mechanics of low-end disruption are much more applicable to business-to-business markets than they are to consumer ones.

Moreover, as I noted in a footnote, Christensen did – to his great credit – own up to his mistaken iPhone prediction in a May, 2012 profile in the New Yorker:1

One CEO who never asked for his help, despite his admiration for The Innovator’s Dilemma, was Steve Jobs, which was fortunate, because Christiansen’s most embarrassing prediction was that the iPhone would not succeed. Being a low-end guy, Christiansen saw it as a fancy cell phone; it was only later that he realized that it was also disruptive to laptops.

It certainly is true that touch devices are disrupting laptops, and if you want to say that started with the iPhone, that’s fine. However, I don’t think this is quite right: note that Christensen’s admission never does say what, exactly, happened to cell phones.

Of course the easy answer is to say “The iPhone disrupted cell phones.” Except, at least to my reading, that kind of misses the point of what disruption is.

As Larissa MacFarquhar wrote in the aforementioned profile:

In industry after industry, Christensen discovered, the new technologies that had brought the big, established companies to their knees weren’t better or more advanced – they were actually worse. The new products were low-end, dumb, shoddy, and in almost every way inferior. The customers of the big, established companies had no interest in them – why should they? They already had something better. But the new products were usually cheaper and easier to use, and so people or companies who were not rich or sophisticated enough for the old ones started buying the new ones, and there were so many more of the regular people than there were of the rich, sophisticated people that the companies making the new products prospered.

Disruption is low-end; a disruptive product is worse than the incumbent technology on the vectors that the incumbent’s customers care about. But, it’s cheaper, and better on other vectors that different customers care about. And, eventually, as the new technology improves, it takes the incumbent’s market.

This is not what happened in cell phones.

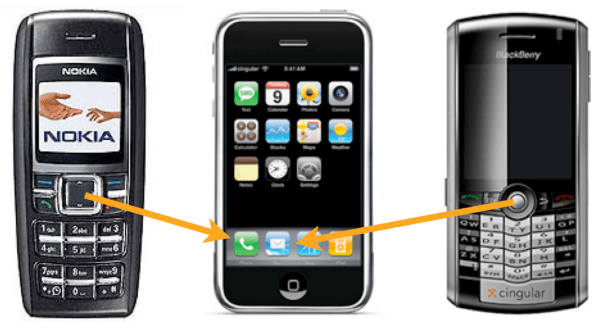

In 2006, the Nokia 1600 was the top-selling phone in the world, and the BlackBerry Pearl the best-selling smartphone.2 Both were only a year away from their doom, but that doom was not a cheaper, less-capable product, but in fact the exact opposite: a far more powerful, and fantastically more expensive product called the iPhone.

The problem for Nokia and BlackBerry was that their specialties – calling, messaging, and email – were simply apps: one function on a general-purpose computer. A dedicated device that only did calls, or messages, or email, was simply obsolete.

An even cursory examination of tech history makes it clear that “obsoletion” – where a cheaper, single-purpose product is replaced by a more expensive, general purpose product – is just as common as “disruption” – even more so, in fact. Just a few examples (think about it – you’ll come up with a bunch more):

- The typewriter and word processor were obsoleted by the PC

- Typesetting was obsoleted by the Mac and desktop publishing

- The newspaper was obsoleted by the Internet

- The CD player was obsoleted by the iPod

- The iPod was obsoleted by the iPhone

Smartphones and app stores have only accelerated this process, obsoleting the point-and-shoot, handheld video games, watches, calculators, maps, and many, many more.

It’s rather striking how often Apple’s products appear on that list. The Mac (and PC), iPod, and iPhone weren’t so much disruptive as they were obsoletive. They absorbed a wide range of specialized tools for a price far greater than any one of those tools cost on their own. It’s reasonable to assume that whatever Apple comes out with next will absolutely be in the same vein.3

As I wrote last week, Christensen’s theory of disruption remains an incredibly elegant and insightful framework for understanding why some companies – like Microsoft, to name the best example – decline. But it’s dramatically over-applied in technology. Most new products are simply better – stop calling them disruptive! – while the most revolutionary products – all of them, ever more personal versions of truly personal computers – are obsoletive. They are more expensive, more capable, and change the way we live.4

Note: This isn’t a new idea by any means. But I think language and word choices are important. Other potential names: subsumative, obviative, absorbative. But not disruptive.

Subscription only, unfortunately. Moreover, the archives – basically, Adobe DPS folios on the web – are nearly unusable. Alas ↩

A theme I have returned to frequently on this blog is the importance of distinguishing between horizontal and vertical business models – hardware and services, in mobile. It is the former, hardware, that seems most receptive to obsoletive technologies, driven by Moore’s Law. It is services, though, due to the zero marginal cost of serving customers, where disruption is a much more applicable theory. It’s Google, then, and Amazon to a degree, that are the most disruptive of companies, but primarily to other horizontal services, not necessarily to differentiated hardware that has inherent value. ↩

If obsoletive products are disruptive, it is only because the parts that obsolete existing technology – like games on the iPhone, for example – are worse than existing technology according to vectors valued by, in this example, console customers. Still, though, this seems to be twisting the example much too far to support the theory when a simpler description – “obsoletive” – will do ↩