I’m a bit late to the most recent flareup around app store pricing – it’s been a busy week of traveling – but it’s worth noting that the trend towards free is basically inevitable and the expected result in a functioning market. To put it another way, apps want to be free just like apples want to fall to the ground – it’s natural and takes truly impressive efforts to work against the gravitational pull.

Natural Prices and Marginal Costs

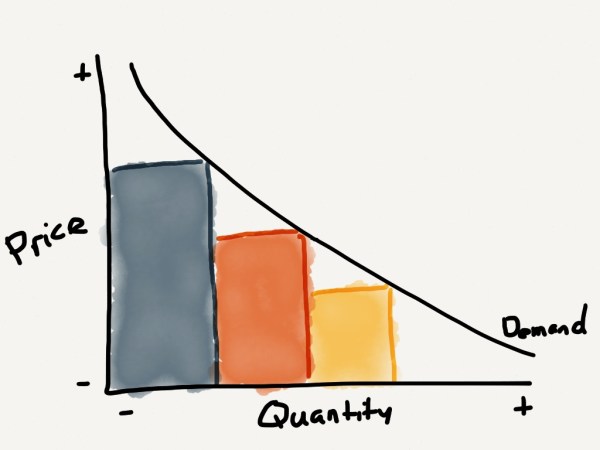

The price of a good is directly related to three factors: the demand for said good, the supply of said good, and the marginal cost of producing said good.

I discussed the demand curve previously in my pre-event analysis of what the iPhone 5C might cost.

In the case of the iPhone, the quantity sold depends on the price. Were Apple to lower the price, they would sell more iPhones.

Apple is in a unique position in that they have “pricing power.” Because they are the only company to produce “iPhones,” they can decide how to price them.1

When a viable substitution good enters the market, like an Android-based smartphone, it is able to sell the same product for a lower price, thus capturing more of the market.

Moreover, if the higher-priced good is not differentiated, then the lower-priced good will not just capture more of the market, but steal the incumbent’s market share as well.

Then, another substitution good enters the market, at an even lower price, increasing the market further, and stealing from both incumbents if they are not differentiated.

This is exactly what happened to the PC market. Because all PCs ran Windows on top of Intel chips, there was no differentiation, and prices dropped.

The floor for this price cutting is called the “natural price,” and is equal to the marginal cost of the good.

The marginal cost of a good is the cost of producing one more of the good in question. Thus, in the case of the iPhone, for example, the marginal cost is how much it costs to produce one more iPhone, which, according to iSuppli, is $199 for the iPhone 5S.

It is important to note that the marginal cost does not include any of the costs of designing or developing the good. Apple has spent hundreds of millions of dollars developing the iPhone over the years, but that is immaterial when it comes to the cost of producing just one more iPhone. After all, that money has already been spent.

The Marginal Cost of Software

What makes the software market so fascinating from an economic perspective is that the marginal cost of software is $0.2 After all, software is simply bits on a drive, replicated at the blink of an eye. Again, it doesn’t matter how much effort was needed to create said software; that’s a sunk cost. All that matters is how much it costs to make one more copy – $0.

The implication for apps is clear: any undifferentiated software product, such as your garden variety app, will inevitably be free. This is why the market for paid apps has largely evaporated. Over time substitutes have entered the market at ever lower prices, ultimately landing at their marginal cost of production – $0.

Making Money with Apps

It is possible to charge for apps, as Joe Cieplinski argued in One Size Fits Some, but the lack of trials and paid upgrades makes this a difficult road to sustainable revenue.

Instead, app developers would do well to look at one of the most interesting phenomenas of our time: open source. At first glance, open source doesn’t make much sense: why would there be so much effort around a “free” product? Yet, given that the marginal cost of software is zero, suddenly free doesn’t seem so strange – it is, in fact, totally natural.

Moreover, lots of money is made with open source software as one of the major components, and individuals and companies looking to build sustainable businesses with apps should take note:

- Google gives away Android to ensure access to their services, data collection, and ads (which is where the money is made). Similarly, many successful developers give away apps in order to serve ads or to provide access to monetized services

- OEMs like Samsung use open source software – again, Android – to make money on hardware. Similarly, more and more developers are experimenting with selling hardware at a profit with free apps as the differentiator (appropriately, Nest launched their second product just today)

- Oracle offers a basic version of MySQL under a GPL license, with additional closed source – and expensive! – add-ons that better fit specific businesses’ needs. The allegory here is in-app purchase: a basic experience that gets the user invested in your product, with value-added options that are more attractive because of said investment

- Companies like IBM contribute heavily to open source and monetize through professional services which install and train users. It’s not a perfect analog, but there are lots of apps that enable monetization through physical services; think a Starbucks app, or any e-commerce app

- Red Hat and others seek to be a platform provider, with a product that is more meaningful than standalone alternatives because of Redhat’s unification of disparate pieces. Apps like LINE take a similar approach, using a free core app to drive adoption of a whole range of platform services and companion apps

It’s natural and understandable for app developers to push for paid download pricing; such a scheme holds the allure of simply letting a developer do what he or she loves – develop – and have money magically appear. Ultimately, though, for most developers, it’s no different than contributing to an open source project and hoping to receive payment. It’s not going to happen for most, especially because Apple just isn’t interested in letting it happen.

Instead, the app store is like any market: your revenue baseline is the cost of the goods you create, and profit is found through differentiation above and beyond that. In the case of software, the natural price is $0 but the differentiation that can be created through software to monetize elsewhere is effectively infinite.