It’s been a long time since an open source project has gotten as much buzz and attention as Docker. The easiest way to explain the concept is, well, to look at the logo of the eponymous1 company that created and manages the project:

The reference in the logo is to shipping containers, one of the most important inventions of the 20th century. Actually, the word “invention” is not quite right: the idea of putting bulk goods into consistently-sized boxes goes back at least a few hundred years.2 What changed the world was the standardization of containers by a trucking magnate named Malcom McLean and Keith Tantlinger, his head engineer. Tantlinger developed much of the technology undergirding the intermodal container, especially its corner casting and Twistlock mechanism that allowed the containers to be stacked on ships, transported by trucks, and moved by crane. More importantly, Tantlinger convinced McLean to release the patented design for anyone to copy without license, knowing that the technology would only be valuable if it were deployed in every port and on every transport ship in the world. Tantlinger, to put it in software terms, open-sourced the design.

Shipping containers really are a perfect metaphor for what Docker is building: standardized containers for applications.

- Just as the idea of a container wasn’t invented by Tantlinger, Docker is building on a concept that has been around for quite a while. Companies like Oracle, HP, and IBM have used containers for many years, and Google especially has a very similar implementation to Docker that they use for internal projects. Docker, though, by being open source and community-centric, offers the promise of standardization

- It doesn’t matter what is inside of a shipping container; the container itself will fit on any ship, truck, or crane in the world. Similarly, it doesn’t matter what app (and associated files, frameworks, dependencies, etc.) is inside of a docker container; the container will run on any Linux distribution and, more importantly, just about every cloud provider including AWS, Azure, Google Cloud Platform, Rackspace, etc.

- When you move abroad, you can literally have a container brought to your house, stick in your belongings, and then have the entire thing moved to a truck to a crane to a ship to your new country. Similarly, containers allow developers to build and test an application on their local machine and have confidence that the application will behave the exact same way when it is pushed out to a server. Because everything is self-contained, the developer does not need to worry about there being different frameworks, versions, and other dependencies in the various places the application might be run

The implications of this are far-reaching: not only do containers make it easier to manage the lifecycle of an application, they also (theoretically) commoditize cloud services through the age-old hope of “write once run anywhere.” More importantly, at least for now, docker containers offer the potential of being far more efficient than virtual machines. Relative to a container, using virtual machines is like using a car transport ship to move cargo: each unique entity on the ship is self-powered, which means a lot of wasted resources (those car engines aren’t very useful while crossing the ocean). Similarly, each virtual machine has to deal with the overhead of its own OS; containers, on the other hand, all share the same OS resulting in huge efficiency gains.3

In short, Docker is a really big deal from a technical perspective. What excites me, though, is that the company is also innovating when it comes to their business model.

The problem with monetizing open source is self-evident: if the software is freely available, what exactly is worth paying for? And, unlike media, you can’t exactly stick an advertisement next to some code!

For many years the default answer has been to “be like Red Hat.” Red Hat is the creator and maintainer of the Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) distribution, which, like all Linux distributions, is freely available.4 Red Hat, however, makes money by offering support, training, a certification program, etc. for enterprises looking to use their software. It is very much a traditional enterprise model – make money on support! – just minus the up-front license fees.

This sort of business is certainly still viable; Hortonworks is set to IPO with a similar model based on Hadoop, albeit at a much lower valuation than it received during its last VC round. That doesn’t surprise me: I don’t think this is a particularly great model from a business perspective.

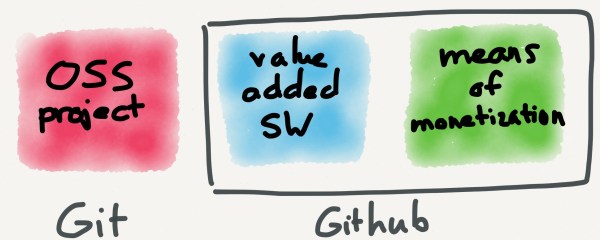

To understand why it’s useful to think about there being three distinct parts of any company that is based on open source: the open source project itself, any value-added software built on top of that project, and the actual means of making money:

The problem with the “Red Hat” model is the complete separation of all three of these parts: Red Hat doesn’t control the core project (Linux), and their value-added software (RHEL) is free, leaving their money-making support program to stand alone. To the company’s credit they have pulled this model off, but I think a big reason is because utilizing Linux was so much more of a challenge back in the 90s.5 I highly doubt Red Hat could successfully build a similar business from scratch today.

GitHub, the repository hosting service, is exploring what is to my mind a more compelling model. GitHub’s value-added software is a hosting service based on Git, an open-source project designed by Linux creator Linus Torvalds. Crucially, GitHub is seeking to monetize that hosting service directly, both through a SaaS model and through an on-premise enterprise offering6. This means that, in comparison to Red Hat, there is one less place to disintermediate GitHub: you can’t get their value-added software (for private projects – public is free) unless you’re willing to pay.

Docker takes the GitHub model a step further: the company controls everything from the open source project itself to the value-added software (DockerHub) built on top of that, and, just last week, announced a monetization model that is very similar to GitHub’s enterprise offering. Presuming Docker continues its present momentum and finds success with this enterprise offering, they have the potential to be a fully integrated open source software company: project, value-added software, and monetization all rolled into one.

This is exciting, and, to be honest, a little scary. What is exciting is that very few movements have had such a profound effect as open source software, and not just on the tech industry. Open source products are responsible for end user products like this blog; more importantly, open source technologies have enabled exponentially more startups to get off the ground with minimal investment, vastly accelerating the rate of innovation and iteration in tech.7 The ongoing challenge for any open source project, though, is funding, and Docker’s business model is a potentially sustainable solution not just for Docker but for future open source technologies.

That said, if Docker is successful, over the long run commercial incentives will steer the Docker open source project in a way that benefits Docker the company, which may not be what is best for the community broadly. That is what is scary about this: might open source in the long run be subtly corrupted by this business model? The makers of CoreOS, a stripped-down Linux distribution that is a perfect complement for Docker, argued that was the case last week:

We thought Docker would become a simple unit that we can all agree on. Unfortunately, a simple re-usable component is not how things are playing out. Docker now is building tools for launching cloud servers, systems for clustering, and a wide range of functions: building images, running images, uploading, downloading, and eventually even overlay networking, all compiled into one monolithic binary running primarily as root on your server. The standard container manifesto was removed. We should stop talking about Docker containers, and start talking about the Docker Platform. It is not becoming the simple composable building block we had envisioned.

This, I suppose, is the beauty of open source: if you disagree, fork, which is essentially what CoreOS did, launching their own “Rocket” container.8 It also shows that Docker’s business model – and any business model that contains open source – will never be completely defensible: there will always be a disintermediation point. I suspect, though, that Rocket will fail and Docker’s momentum will continue: the logic of there being one true container is inexorable, and Docker has already built up quite a bit of infrastructure and – just maybe – a business model to make it sustainable.

For the grammar nerds, I subscribe to the notion that eponymous can be used in either direction ↩

Security is one of the biggest questions facing Docker: is it possible to guarantee that apps cannot interact or interfere with each other? Currently the conventional wisdom is that containers shouldn’t be used for multi-tenant applications, but that security is good enough for multiple applications from a single tenant ↩

Technically, the source code is available, but any derivatives must strip-out all Red Hat trademarks ↩

Fun fact: Red Hat was the first version of Linux I ever installed. It did not go well ↩

BitBucket from Atlassian is similar; from a business model perspective the primary difference is that GitHub prices per repository while Atlassian prices per user ↩

In fact, one could argue that open source is the number one argument against there being a bubble: there are so many startups not because there is an inordinate amount of money available, but because it is so damn cheap to get off the ground. Moreover, the standards for gaining meaningful funding are now way higher: because it is so much cheaper to build, test, and iterate on an idea, a startup needs traction before investors will write a check ↩

It’s not precisely a fork; Rocket is new from the ground up but designed to do what Docker does and nothing more ↩