Yesterday’s Apple keynote was one of the company’s best in quite some time.1 One reason why was, as John Gruber noted, a certain sense of stagecraft, editing, and overall flow that has at times been missing in recent keynotes; I think a bigger reason, though, was the simple fact that Apple launched a whole bunch of new hardware products — the new iPad Pro, the new Apple TV, and, of course, updated iPhones — and new hardware makes for compelling keynotes.

If the last decade-and-a-half has taught us anything, it is that Apple is really, really good at making hardware products, for a whole bunch of reasons. As CEO Tim Cook and his fellow presenters repeat at every opportunity, the fact the company controls both the hardware and software layers is critical; less remarked upon but just as important is the way in which Apple’s massive cash position enables the company to spare no expense when it comes to designing, producing, and scaling new products. Similarly, Apple’s scale gives them unmatched leverage in the global supply chain, ensuring Apple always has the best components made in the best factories for the best prices.

More fundamentally, Apple is a company that is completely aligned and incentivized by said products. Start with the fact that designers — industrial designers in particular — are firmly in charge of product development. Ian Parker noted, in his New Yorker profile of Apple Chief Design Officer Jony Ive:

Apple’s designers have long had an influence in the company which is barely imaginable to most designers elsewhere. This power “was anointed to them by Steve, and enforced by Steve, and has become embedded culturally,” in the description of Robert Brunner, who gave Ive his first job at Apple, and ran Apple’s design group in the first half of the nineteen-nineties, before this culture took hold. Jeremy Kuempel, an engineer who interned at the company a few years ago, and has since launched a coffee-machine startup, told me that when a designer joined a meeting at Apple it was “like being in church when the priest walks in.”

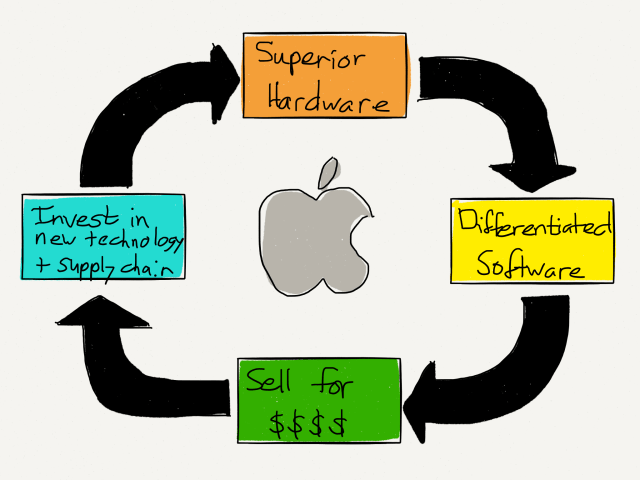

It’s a lot easier to give the designers control when Apple’s business model is predicated on achieving high margin, not necessarily the lowest possible cost. Relatedly, all of the company’s software development, from operating systems to cloud services, exists to differentiate the hardware, not to make money in their own right,2 resulting in a virtuous cycle that means it is becoming more difficult to compete with Apple’s hardware products over time.

This cycle of design, differentiation, profit-taking, and reinvestment is seen most clearly in the iPhone. While the processor has improved in every iPhone generation, that improvement has accelerated over recent generations; a similar rate of improvement has come to the iPhone’s cameras. Similarly, both the 5S and the 6S have added important new features like Touch ID and now 3D Touch, in contrast to the 3GS and 4S which were largely the same feature-wise as their predecessors. When you combine these improvements with the fact one’s phone is the most important and most used possession one has, the lure of an annual upgrade is very strong indeed.3

That bit about one’s phone being one’s most important and most used possession is critical: Apple’s cycle of accelerating improvement only matters to the extent that iPhone customers perceive benefit from those improvements. It is easier, though, to perceive and value those benefits the more you use a device, and the more uses a device has; to put it another way, an infinite number of interactions with a slight improvement is even more valuable than a few interactions with a huge improvement. By extension, the mistake made by Apple bears who continually claim the iPhone is “good enough” is to underestimate just how much people use and value their phones.

The Good Enough iPad

The “good enough” critique, though, certainly applies to the iPad; while a smartphone and all of the social and communications apps that run on it are a necessity for nearly everyone, for many the iPad simply doesn’t have that many use cases beyond, perhaps, video, an activity that worked just fine on the original iPad. And so, most iPad owners have declined to upgrade, and just as many if not more iPhone owners haven’t even bothered to buy an iPad at all; as a result, sales have plummeted for several years now.

This is the context for the new iPad Pro; Cook introduced the product as follows (emphasis mine):

“Next up is iPad. iPad is the clearest expression of our vision of the future of personal computing. A simple multi-touch piece of glass that instantly transforms into virtually anything that you want it to be. In just five years the iPad has transformed the way we create, the way we learn, and the way we work. We’re partnering with the world’s leading enterprise companies, IBM and Cisco, to redefine and transform the way people work in the enterprise. As we’ve brought more and more capability and more and more power to the iPad we’ve been amazed at the new and unexpected things that our customers have done with the iPad. So we asked ourselves, how could we take iPad even further? Today, we have the biggest news in iPad since the iPad. And I am thrilled to show it to you.

Note that phrase: “How could we take the iPad even further?” Cook’s assumption is that the iPad problem is Apple’s problem, and given that Apple is a company that makes hardware products, Cook’s solution is, well, a new product.

My contention, though, is that when it comes to the iPad Apple’s product development hammer is not enough. Cook described the iPad as “A simple multi-touch piece of glass that instantly transforms into virtually anything that you want it to be”; the transformation of glass is what happens when you open an app. One moment your iPad is a music studio, the next a canvas, the next a spreadsheet, the next a game. The vast majority of these apps, though, are made by 3rd-party developers, which means, by extension, 3rd-party developers are even more important to the success of the iPad than Apple is: Apple provides the glass, developers provide the experience.

That, then, means that Cook’s conclusion that Apple could best improve the iPad by making a new product isn’t quite right: Apple could best improve the iPad by making it a better platform for developers. Specifically, being a great platform for developers is about more than having a well-developed SDK, or an App Store: what is most important is ensuring that said developers have access to sustainable business models that justify building the sort of complicated apps that transform the iPad’s glass into something indispensable.

That simply isn’t the case on iOS. Note carefully the apps that succeed on the iPhone in particular: either the apps are ad-supported (including the social networks that dominate usage) or they are a specific type of game that utilizes in-app purchasing to sell consumables to a relatively small number of digital whales. Neither type of app is appreciably better on an iPad than on an iPhone; given the former’s inferior portability they are in fact worse.

A very small number of apps are better on the iPad though: Paper, the app used to create the illustrations on this blog, is a brilliantly conceived digital whiteboard that unfortunately makes no money; its maker, FiftyThree, derives the majority of its income from selling a physical stylus called the Pencil (now eclipsed in both name and function by Apple’s new stylus).4 Apple’s apps like Garageband and iMovie are spectacular, but neither has the burden of making money.

The Developer Problem

The problem for iPad developers is three-fold:

- First, the lack of trials means that genuinely superior apps are unable to charge higher prices because there is no way to demonstrate to consumers prior to purchase why they should pay more. Some apps can hack around this with in-app purchases, but purposely ruining the user experience is an exceedingly difficult way to demonstrate that your experience is superior

- Secondly, the lack of a simple upgrade path (and upgrade pricing) makes it difficult to extract additional revenue from your best customers; it is far easier to get your fans to pay more than it is to find completely new customers forever. Again, developers can hack around this by simply releasing completely new apps, but it’s a poor experience at best and there is no way to reward return customers with better pricing, or, more critically, to communicate to them why they should upgrade

- That there is the third point: Apple has completely intermediated the relationship between developers and their customers. Not only can developers not communicate news about upgrades (or again, hack around it with inappropriate notifications), they also can’t gain qualitative feedback that could inspire the sort of improvements that would make an upgrade attractive in the first place

These mechanisms work: they are the core of the Mac application ecosystem which has been thriving with a far smaller user base for years now.5 Absent their implementation it is simply foolhardy to invest the sort of time and resources necessary to transform the iPad’s glass into the experiences that make it worth owning, and by extension, overly optimistic to think that a form factor change will bend the iPad growth curve up and to the right.

The Return of Microsoft

There was obvious symbolism in Microsoft’s appearance during the iPad Pro’s introduction; after all, it was not the first time the company had made an appearance at an Apple keynote:6

These images are from MacWorld Boston in 1997, where Steve Jobs announced that Microsoft was investing money in the nearly bankrupt Apple and, more importantly, committing to a Mac version of Office.

The reality for Jobs and Apple was that the company’s users needed Office (along with Adobe’s products) more than they needed a Mac. I’ve long argued that being in this position is a big reason why Apple hasn’t enabled sustainable apps: never again would a software developer hold Apple hostage. The irony, though, is that when it came time to launch the iPad Pro, Apple had no one else to turn to.

Over the last several years both Microsoft and Adobe have altered their business models away from packaged software towards subscription pricing; while their users may have grumbled, they also had no choice given their dependence on the two software giants’ products. And, it’s that new model that justifies the expense of developing iPad apps and explains why it is Apple’s old nemeses who are doing by far the most interesting work on the iPad.7 Unfortunately, this isn’t a model that is readily replicable for the sort of development shops that Apple needs to invest significant time and resources in creating must-have iPad apps: what customer is going to sign up for a recurring payment for an app that doesn’t even have a service component and that the customer hasn’t even tried?

What’s fascinating to consider is that it’s arguable the iPad would actually be in a much better position were it owned by Microsoft: the company is at its core a platform company that has long bent over backwards to accommodate its developers even at the expense of the user experience. That, though, is the rub: in consumer markets the only way to gain the prerequisite scale to be a platform is to first have a superior product, like Apple. More than ever each has what the other needs.

The Need to Let Go

Long-time readers know this isn’t the first time I’ve written about Apple’s inability to foster a healthy app ecosystem (again, beyond front-ends for ad-supported services, free-to-play games, or the most simple of apps) and how I believe that inability has held the iPad back. The concern, though, is that it is very possible to envision the Apple TV going down the iPad route. Apple’s declaration that “The Future of TV is Apps” is a very compelling one, but the degree to which that vision is realized is inextricably tied to the prospects developers have for making money.

Ultimately, for Apple, as diligently as the company may have worked on the iPad Pro and Apple TV, the truly difficult part begins now: the company remains far ahead of nearly anyone else in the world at creating great products, in part by zealously controlling everything from core technology to the supply chain to the retail experience. Platforms, though, while established through product leadership, flourish and sustain themselves by empowering and entrusting developers to build something so compelling that customers fall in love with not just the hardware but the experience that runs on top of it. In short, they require sharing the customer relationship, and while that may go against Apple’s instincts, to not do so is increasingly against Apple’s interests.

Tomorrow’s Daily Update will cover the specifics of yesterday’s event from beginning to end

I think you have to go back to the 2013 iPhone 5S launch to find one of similar quality ↩

Apple Music is the glaring exception ↩

Conveniently, U.S. carriers have made giving in to that temptation much more viable thanks to their move away from subsidized contracts to direct phone financing and attractive buy-back programs, a shift that benefits Apple ↩

Relatedly, FiftyThree just today announced Paper for iPhone ↩

In fact, the biggest challenge I find in using Windows regularly is not the OS itself, which is quite solid and has several features I prefer over OS X; rather, I simply can’t do without many of my favorite Mac apps and utilities, several of which have been in active development for years ↩

To be clear, Microsoft appeared at many Apple keynotes over the years ↩

Although, word on the street is that at least one of them is increasingly frustrated at how little financial return their apps offer ↩