In the hours after The New York Times broke the story that Instagram co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger had resigned from Instagram, the question quickly turned to why; the immediate culprit was everyone’s favorite punching bag, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg:

- Bloomberg: The founders of Instagram are leaving Facebook Inc. after growing tensions with Chief Executive Officer Mark Zuckerberg over the direction of the photo-sharing app, people familiar with the matter said.

- TechCrunch: According to TechCrunch’s sources, tension had mounted this year between Instagram and Facebook’s leadership regarding Instagram’s autonomy. Facebook had agreed to let it run independently as part of the acquisition deal. But in May, Instagram’s beloved VP of Product Kevin Weil moved to Facebook’s new blockchain team and was replaced by former VP of Facebook News Feed Adam Mosseri — a member of Zuckerberg’s inner circle.

- Recode: Instagram co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger are resigning from the company they built amid frustration and agitation with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s increased meddling and control over Instagram, according to sources.

All of these stories are interesting, and undoubtedly more details will come out over the next few days. At the same time, by virtue of looking at events that occurred over the past few weeks or months or even years, they all fundamentally miss the point. The date that matters when it comes to understanding these resignations is April 9, 2012, and the people most responsible are Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger.

Extraordinary Product Leaders

Zuckerberg’s statement about Systrom and Krieger’s resignation was quite terse, and perhaps for that reason, rather revealing:

“Kevin and Mike are extraordinary product leaders and Instagram reflects their combined creative talents. I’ve learned a lot working with them for the past six years and have really enjoyed it. I wish them all the best and I’m looking forward to seeing what they build next.”

Calling Systrom and Krieger “extraordinary product leaders” is high praise, and remarkably enough, an understatement.

Instagram started out as a Foursquare-esque check-in app called Burbn, but when Systrom and Krieger realized that Brbn’s users were not checking in but were sharing photos like crazy, the pair quickly built a new app called Instagram. MG Siegler wrote at the time, in a remarkably prescient synopsis:

Unlike Burbn, Instagram is neither a location-based app (though that is one component), nor is it HTML5-based. But it did spring out of the way co-founders Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger saw people using Burbn. That is: quick, social sharing — and a desire to share photos from places. That’s the foundation of Instagram.

More specifically, Instagram is a iPhone photo-sharing application that allows you to apply interesting filters to your photos to make them really pop…Once you take a picture and apply a filter (there’s also an option not to), the photo is shared into your Instagram Feed. From here, your friends on the site can “like” or comment on it. But another key to Instagram is that it’s just as easy to share these photos to other social networks — like Twitter, Facebook, and Flickr.

Nearly all of the key pieces were there from the beginning:

- Instagram had a reason to download: cool filters that, unlike the competition, were free.

- Instagram had a great user experience: instantaneous sharing to social networks, without jumping through “Save to Camera Roll” hoops.

- Instagram had the seeds of something much greater than a photo editing app: it was, from the beginning, a social network in its own right; as Chris Dixon describes it, “Come for the tool, stay for the network.”

Instagram took off like a rocket, and had 10 million users in a year; that number would triple within the next six months, and was set to grow even faster when the startup finally launched an Android version, which racked up 1 million downloads in 24 hours. That is when Facebook came in with an offer Systrom and company couldn’t refuse: $1 billion in cash and stock for, well, for what?

Technically speaking, Instagram was a company. In practice, though, Instagram was a product, and its business model was venture capital funding. To be sure, this wouldn’t be the case forever, but on April 9, 2012, the road from popular product to viable company was a long and arduous one. Instagram would not only need to continue growing its user base, it would also have to scale its infrastructure, figure out a business model (ok fine, advertising), build up tools to support that business model (first a sales team, then a self-serve model, plus tracking and targeting capabilities), all while fighting off larger and more established companies — particularly Facebook — that were waking up to the threat Instagram posed to their hold on user attention.

Or Systrom and Instagram could offload all of those responsibilities to Facebook and continue being “extraordinary product leaders”, and pocket $1 billion to boot (and, to be fair to Systrom and team, that understates their gains; that $1 billion included $700 million in Facebook stock, which today is worth nearly $4 billion). It is a defensible choice (for Instagram anyways; not for the regulators that approved the deal), but the implication is that, title notwithstanding, Systrom was never the CEO of Instagram; to be a CEO is to have a company that can stand on its own.

The difference from Zuckerberg — Instagram’s real CEO — is stark. Facebook launched in February, 2004, and sold its first ad two months later. True, “Facebook Flyers” bear little resemblance to the News Feed ads that power the company today, but Zuckerberg’s immediate instinct to build not just a product but a company is notable. Indeed, it casts a new light on the brash CEO’s (in)famous business cards:

He was indeed, in title and in practice. To be CEO — to have control — is, at least in the long run, not simply about building a great product. It is about finding and developing a business model that lets you determine your own destiny.

How the Snapchat Threat Was Vanquished

Probably the pinnacle of Systrom and Zuckerberg’s collaboration — extraordinary product leader and ruthless CEO — was Instagram Stories. Systrom freely admitted that the concept was copied from Snapchat; as I noted at the time, that would certainly be good enough given Instagram’s larger network:

Instagram and Facebook are smart enough to know that Instagram Stories are not going to displace Snapchat’s place in its users lives. What Instagram Stories can do, though, is remove the motivation for the hundreds of millions of users on Instagram to even give Snapchat a shot.

Getting consumer adoption of new products is hard; when that adoption requires a network, it’s harder still, at least if most of your network is not using said product; on the flipside, those same difficulties become massive accelerants once the product passes a certain threshold of your friends. Snapchat has passed that threshold amongst teenagers and increasingly young adults in the United States, and every day gets closer with other demographics and geographies.

Instagram, though, is already there, but with a product that does Facebook’s job of presenting your best self. What makes this move so audacious is Zuckerberg and Systrom’s bet that they can refashion Instagram into a product for being yourself, at least to a sufficient degree to hold off Snapchat’s ongoing suction of attention.

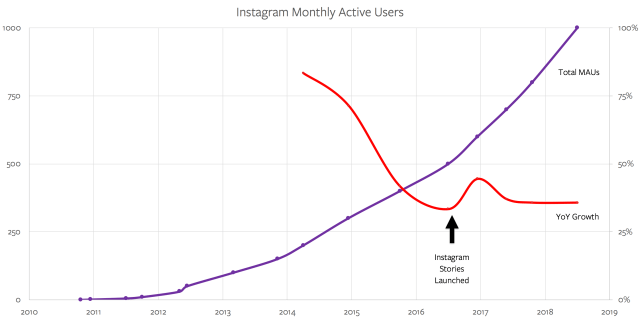

That article was mostly spot-on; my primary error was underestimating just how good Instagram’s product would be. Instagram Stories from day one were a better experience than Snapchat Stories, particularly in terms of speed; the product differences only grew from there. Ultimately, Instagram Stories didn’t simply stem Snapchat’s growth; it actually accelerated Instagram’s:

Meanwhile, Zuckerberg and Facebook’s ad team were cutting off Snapchat’s monetization oxygen, as I explained in Facebook’s Lenses:

Facebook spent years building out News Feed advertising — not simply the display and targeting technology but also the entire back-end apparatus for advertisers, connections with non-Facebook data sources and points-of-sale, relationships with ad buyers, etc. — and then simply plugged Instagram into that infrastructure.

The payoff of this integrated approach cannot be overstated. Instagram got to scale in terms of monetization years faster than they would have on their own, even as the initial product team had the freedom to stay focused on the user experience. Facebook the app benefited as well, because Instagram both increased the surface area for Facebook ad campaigns even as it increased Facebook’s targeting capabilities.

The biggest impact, though is on potential competition. It is tempting to focus on the “R” in “ROI” — the return on investment — and as I just noted Instagram + Facebook makes that even more attractive. Just as important, though, is the “I”; there is tremendous benefit to being a one-stop shop for advertisers, who can save time and money by focusing their spend on Facebook. The tools are familiar, the buys are made across platforms, and as Zuckerberg and Sandberg alluded to with regard to Stories, the ads themselves only need to be made once to be used across multiple platforms. Why even go to the trouble to advertise anywhere else?

This dynamic, by the way, was very much apparent when Snap IPO’d a year-and-a-half ago; indeed, Snap CEO Evan Spiegel, often cast as the anti-Systrom — the CEO that said “No” to Facebook — arguably had the same flaw. Systrom offloaded the building of a business to Zuckerberg; Spiegel didn’t bother until it was much too late.

Instagram’s Challenge

Still, as good as the Instagram Stories product was, it is difficult to overstate the built-in advantage that came from Instagram’s larger network, and impossible to overstate the importance of having a shared advertising backend with Facebook. To put it another way, Instagram’s two biggest advantages relative to Snapchat, or any other competitors that may arise, didn’t have much to do with product — Systrom’s speciality — at all.

There is no better example than IGTV. Three months ago Systrom announced Instagram’s new long-form video offering with a presentation that exuded product sensibility. I marveled at the time:

In just a few minutes Systrom brilliantly and, to my mind, accurately, explained how video consumption was changing for teenagers in particular, highlighted how current solutions (i.e. YouTube) fell short, and set out the principles that should guide the creation of a better service (mobile first, simple, and high quality videos). And, naturally, that better service was IGTV.

It doesn’t seem to have mattered in the slightest. Josh Constine wrote a smart article about IGTV’s struggles last month on TechCrunch:

It’s indeed too early for a scientific analysis, and Instagram’s feed has been around since 2010, so it’s obviously not a fair comparison, but we took a look at the IGTV view counts of some of the feature’s launch partner creators. Across six of those creators, their recent feed videos are getting roughly 6.8X as many views as their IGTV posts. If IGTV’s launch partners that benefited from early access and guidance aren’t doing so hot, it means there’s likely no free view count bonanza in store from other creators or regular users. They, and IGTV, will have to work for their audience. That’s already proving difficult for the standalone IGTV app. Though it peaked at the #25 overall US iPhone app and has seen 2.5 million downloads across iOS and Android according to Sensor Tower, it’s since dropped to #1497 and seen a 94 percent decrease in weekly installs to just 70,000 last week.

The one big surprise of the launch event was where IGTV would exist. Instagram announced it’d live in a standalone IGTV app, but also as a feature in the main app accessible from an orange button atop the home screen that would occasionally call out that new content was inside. It could have had its own carousel like Stories or been integrated into Explore until it was ready for primetime. Instead, it was ignorable. IGTV didn’t get the benefit of the home screen spotlight like Instagram Stories. Blow past that one orange button and avoid downloading the separate app, and users could go right on tapping and scrolling through Instagram without coming across IGTV’s longer videos. View counts of the launch partners reflect that.

I’m not arguing that product doesn’t matter. It does, incredibly so. But it is not the only thing that matters, and its relative importance decreases over time as things like network effects and business models come to bear. To that end, the single most important issue facing Instagram — the company that is, or, more accurately, Facebook — is Stories monetization. I wrote last month in Facebook’s Story Problem — and Opportunity:

That’s the thing about Stories, though: while more people may use Instagram because of Stories, some significant number of people view Stories instead of the Instagram News Feed, or both in place of the Facebook News Feed. In the long run that is fine by Facebook — better to have users on your properties than not — but the very same user not viewing the News Feed, particularly the Facebook News Feed, may simply not be as valuable, at least for now.

This is the context for whatever dispute drove Systrom and Krieger’s resignation: not only do they not actually control their own company (because they don’t control monetization), they also aren’t essential to solving the biggest issue facing their product. Instagram Stories monetization is ultimately Facebook’s problem, and in case it wasn’t clear before, it is now obvious that Facebook will provide the solution.

I don’t write any of this to denigrate Systrom and Krieger in the slightest. If anything my appreciation for their incredible product sense has only grown over the last few years. Both are truly extraordinary, as is their creation.

Controlling one’s own destiny, though, takes more than product or popularity. It takes money, which is to say it takes building a company, working business model and all. That is why I mark April 9, 2012, as the day yesterday became inevitable. Letting Facebook build the business may have made Systrom and Krieger rich and freed them to focus on product, but it made Zuckerberg the true CEO, and always, inevitably, CEOs call the shots.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.