If you remove the societal impact, just for a moment, the story of publishers’ demise — first newspapers, and now digital-only companies like BuzzFeed and Huffington Post, which both announced significant layoffs last week — is rather banal: infinite competition combined with an inferior product resulted in failed business models.

Infinite competition is the result of the Internet: any piece of content is only a tap away, a far cry from a world where geographic areas were dominated by a small number of newspapers. The inferior product is advertising: when newspapers were the only option, advertising inventory was scarce; now advertisers — which only paid for newspaper space as a matter of convenience, not principle — can reach the exact customers they want exactly where they spend most of their time and attention, namely Facebook and Google. And thus the failed business model: is it any surprise that commoditized content and non-competitive ad inventory did not work?

The BuzzFeed Disappointment

Still, the BuzzFeed layoffs in particular are disappointing, precisely because of the societal importance of journalism. Back in 2015 I wrote that BuzzFeed [Was] the Most Important News Organization in the World:

Perhaps the single most powerful implication of an organization operating with Internet assumptions is that iteration – and its associated learning – is doable in a way that just wasn’t possible with print. BuzzFeed as an organization has been figuring out what works online for over eight years now, and while “The Dress” may have been unusual in its scale, its existence was no accident. What’s especially exciting about BuzzFeed, though, is how it uses that knowledge to make money…

More importantly, with this model BuzzFeed has returned to the journalistic ideal that many — including myself — thought was lost with the demise of newspapers’ old geographic monopolies: true journalistic independence. Just as journalists of old didn’t need to worry about making money, just writing stories that they thought important, BuzzFeed’s writers simply need to write stories that people find important enough to share; the learning that results is how they make money. The incentives are perfectly aligned…The world needs great journalism, but great journalism needs a great business model. That’s exactly what BuzzFeed seems to have, and it’s for that reason the company is the most important news organization in the world.

So what went wrong?

BuzzFeed’s Pivot

It was only two weeks after that post that CEO Jonah Peretti announced a pivot; from an interview with Peter Kafka of Recode:

JP: As [full-stack media companies] started to become received wisdom, it started to stop being true, that it was the best way to build a company, and that happened largely because there was this jump to mobile and to mobile apps, and probably the majority of content consumption is happening inside of mobile apps. You think “Facebook traffic”, but in a way that’s people opening Facebook, seeing a BuzzFeed story, clicking a BuzzFeed story…That has started to create an environment where media is much more distributed…

PK: So you built this system that was optimized for generating traffic and making money from stuff that happened on BuzzFeed.com and now you’re realizing that’s not what you want to do.

JP: What we realized is that that was just one piece of our business…What I’ve been doing is meeting with every team in BuzzFeed with this little chart that is our model for making content that people love — News, Buzz, Life, Video, Lists, Quizzes, all different types of content, and have great tools for making content that people love — and then we send that content to various places. We send it to our own websites and to our own apps, which are owned-and-operated properties and remain important to us, where we have a certain ability to get data and learn from what we’re doing, but we also send it natively to other platforms like YouTube, or Facebook.

2015 was the year that Facebook unveiled Instant Articles: publishers could put their content directly on Facebook, and Facebook, at least in theory, would help them monetize it. That seemed like a great deal! Facebook, for reasons I laid out in Popping the Publishing Bubble, was much better at advertising than any publishing company could hope to be:

In the pre-Internet era publishers had it easy: on one hand, they employed journalists whose goal it was to reach as many readers as possible. On the other, they were largely paid by advertisers, whose goal was to reach as many potential customers as possible. The alignment — reach as many X as possible — was obvious, and profitable for the publishers in particular.

[…]

The shift from paper to digital meant publications could now reach every person on earth (not just their geographic area), and starting a new publication was vastly easier and cheaper than before…The increase in competition destroyed the monopoly, but it was the divorce of “readers” from “potential customers” that prevented even the largest publishers from profiting much from the massive amounts of new traffic they were receiving. After all, advertisers don’t really care about readers; they care about identifying, reaching, and converting potential customers. And, by extension, this meant that differentiating ad inventory depended less on volume and much more on the degree to which a particular ad offered superior targeting, a superior format, or superior tracking.

[…]

The above graph shows the inefficiency of this arrangement: publishers and ad networks are locked in a dysfunctional relationship that doesn’t serve readers or advertisers, and it’s only a matter of time until advertisers — which again, care only about reaching potential customers, wherever they may be — desert the whole mess entirely for new, more efficient and effective advertising options that put them directly in front of the people they care about. That, first and foremost, is Facebook…

With Instant Articles it appeared that the social network would share the spoils: Facebook collects the advertising money, and publishers that embrace the platform share in the reward.

The core problem for BuzzFeed is that never really happened: Instant Articles relied on the Facebook Audience Network, not Facebook’s core News Feed ad product, and nearly all of Facebook’s energy went into the latter. Companies that embraced Instant Articles — and, in the case of BuzzFeed, built their business models around them — were left earning pennies, mostly on programmatic advertising.

Complete Commoditization

For the record, I was completely wrong about the degree to which Facebook would help publishers monetize Instant Articles: it seemed to me that it was in Facebook’s interest to create sustainable models for quality content that lived directly on its platform. Sure, the company would be giving up a slice of its revenue, but the impact on the overall user experience generally and establishing Facebook as the center of not just the consumption of content but the monetization of content specifically would be powerful moats.

The truth, though, is that the short-term incentives to maximize revenue, primarily through News Feed ads that Facebook kept for itself, were irresistible, and besides, the company had other fish to fry: Snapchat was looming as a threat through 2015, and by 2016 the company was starting to warn that ad loads were saturating. Quarterly growth was very much the priority, and once Snapchat was neutralized, was a content-based moat really necessary?

I suspect, thought, that there is a more fundamental reason why BuzzFeed’s strategy was untenable. I wrote about the Conservation of Attractive Profits in the context of Netflix back in 2015:

The Law of Conservation of Attractive Profits,1 [was] first explained by Clayton Christensen in his 2003 book The Innovator’s Solution:

Formally, the law of conservation of attractive profits states that in the value chain there is a requisite juxtaposition of modular and interdependent architectures, and of reciprocal processes of commoditization and de-commoditization, commoditization, that exists in order to optimize the performance of what is not good enough. The law states that when modularity and commoditization cause attractive profits to disappear at one stage in the value chain, the opportunity to earn attractive profits with proprietary products will usually emerge at an adjacent stage.

That’s a bit of a mouthful, but the example that follows in the book shows how powerful this observation is:

If you think about it in a hardware context, because historically the microprocessor had not been good enough, then its architecture inside was proprietary and optimized and that meant that the computer’s architecture had to be modular and conformable to allow the microprocessor to be optimized. But in a little hand held device like the RIM BlackBerry, it’s the device itself that’s not good enough, and you therefore cannot have a one-size-fits-all Intel processor inside of a BlackBerry, but instead, the processor itself has to be modular and conformable so that it has on it only the functionality that the BlackBerry needs and none of the functionality that it doesn’t need. So again, one side or the other needs to be modular and conformable to optimize what’s not good enough.

Did you catch that? That was Christensen, a full four years before the iPhone, explaining why it was that Intel was doomed in mobile even as ARM would become ascendent. When the basis of competition changed away from pure processor performance to a low-power system the chip architecture needed to switch from being integrated (Intel) to being modular (ARM), the latter enabling an integrated BlackBerry then, and an integrated iPhone four years later.2

More broadly, breaking up a formerly integrated system — commoditizing and modularizing it — destroys incumbent value while simultaneously allowing a new entrant to integrate a different part of the value chain and thus capture new value.

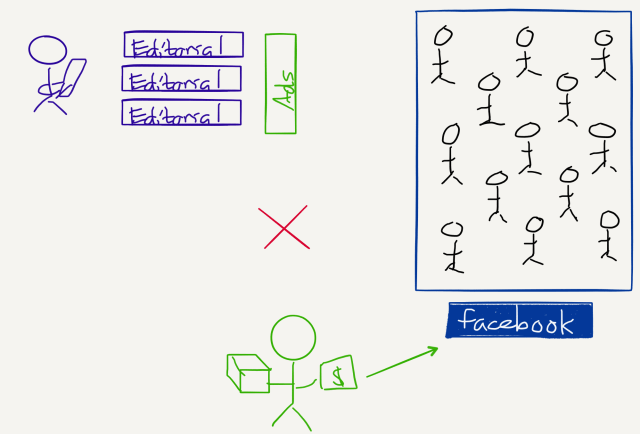

This is the theoretical explanation of what happened to publishers: newspapers previously integrated editorial and advertising:

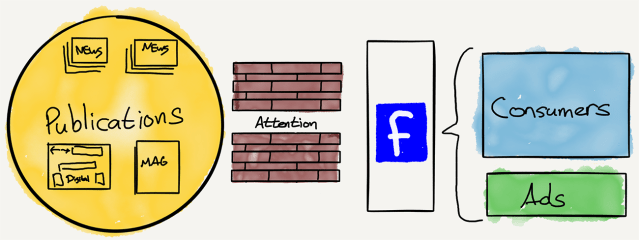

Then Facebook came along and integrated users and advertising:

The result was the commoditization of content that I described above, which is exactly what you would predict given the integration elsewhere in the value chain. What I think is important, though, and under-appreciated by me (which is why I got Instant Articles wrong) is that the scale of integration — and correspondingly, the scale of commoditization — matters as well.

In the case of Facebook the integration is absolute: the social network has two billion users, which gives the company not only a network effect, but also a gargantuan amount of user-generated content to populate the News Feed where the ads targeted with an even larger set of user data can be placed. It follows, then, that content suppliers are absolutely commoditized: Facebook doesn’t need to do anything to keep them on the platform, because where else will they go? Might as well keep the money for itself.

Aggregation and Commoditization

You see a similar dynamic with other large aggregators: Google’s Answer Box trades away the long-term viability of sites generating the content that makes Google useful in exchange for a short-term benefit that, yes, accrues to users, but accrues even more to Google, keeping those users on Google properties. And why not? It is not as if the web is running out of content — indeed, most website owners are paying Google supply sourcing agents SEO specialists to figure out how to get their content into those Answer Boxes in pursuit of whatever crumbs of traffic result.

Amazon is following the same playbook: the company is ramping up its private label business, producing products that compete directly with companies that both sell to Amazon and are on the platform as 3rd-party merchants. After all, Amazon has integrated users and logistics: if suppliers pull their goods they will not pull customers away from Amazon; they’ll simply lose sales.

It’s the same thing with Apple and the App Store: the most valuable customers in most markets are on the iPhone, which is why Apple can get away with charging 30% on digital goods that have nothing to do with the iPhone. Customers are not abandoning iOS just so they can have a better experience buying digital books, and Apple’s management certainly can’t afford a hit in Service revenue, particularly right now.

That’s the thing, though: all of the big aggregators have been pursuing similar policies for years. To point to short-term pressure, whether that be falling China iPhone sales or Facebook ad load saturation is to miss the broader point: the more dominant an aggregator the more powerless the supply, and none of these companies are in the charity business.

Avoiding Aggregators

While I know a lot of journalists disagree, I don’t think Facebook or Google did anything untoward: what happened to publishers was that the Internet made their business models — both print advertising and digital advertising — fundamentally unviable. That Facebook and Google picked up the resultant revenue was effect, not cause. To that end, to the extent there is concern about how dominant these companies are, even the most extreme remedies (like breakups) would not change the fact that publishers face infinite competition and have uncompetitive advertising offerings.

What is clear, though, is that the only way to build a thriving business in a space dominated by an Aggregator is to go around them, not to work with them. In the case of publishers, that means subscriptions, or finding ways to monetize, like the Ringer, beyond text.3 For web properties it means building destination sites that are not completely reliant on Google. For manufacturers it means building relationships with retailers other than Amazon and building brands that compel customers to go elsewhere. And for digital content providers…well, this is why I view Apple’s policies as the most egregious of all.

As for BuzzFeed, it is not as if the company is dead: there is talk of mergers (which makes sense to reduce costs), and multi-pronged monetization strategies that emulate the success of the Tasty cooking videos: the company not only earns video advertising, but creates branded videos, has a line of branded cooking ware, and yes, takes programmatic advertising dollars on the companies owned-and-operated sites. Advertising can augment a publisher, but it’s hard to believe it can support one, even one expressly built for the Internet. That is now the realm of Aggregators.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

Later renamed the Law of Conservation of Modularity ↩

As I’ve noted, the iPhone is in fact modular at the component level; the integration is between the completed phone and the software. Not appreciating that the point of integration (or modularity) can be anywhere in the value chain is, I believe, at the root of a lot of mistaken analysis about the iPhone in particular, including Christensen’s ↩

The Ringer is following the exact strategy I laid out in Grantland and the (Surprising) Future of Publishing ↩