George Soros is famous for his timing.

In 1992 Soros built a massive short position in pound sterling, betting that the United Kingdom had entered European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) at an unsustainably high rate, particularly given British inflation and interest rates relative to Germany; when the pound fell below the minimum level allowed by the ERM, Soros pounced, selling so much sterling that the government could not prop up the currency. The United Kingdom withdrew from the ERM, the pound plummeted, and Soros pocketed over £1 billion in profit.

That, though, was then; last week Soros penned an opinion column in the New York Times that basically stated that Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg was actively working to re-elect President Trump. Much of it reads like a conspiracy theory — and the part on Section 230 is so mistaken it is, ironically enough, bordering on disinformation — but what was particularly striking was how poor the timing was; Soros concluded:

I repeat and reaffirm my accusation against Facebook under the leadership of Mr. Zuckerberg and Ms. Sandberg. They follow only one guiding principle: maximize profits irrespective of the consequences. One way or another, they should not be left in control of Facebook.

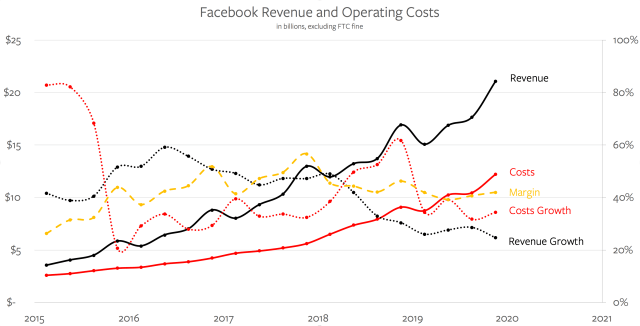

In fact, Facebook reported its financial results two days before Soros’ op-ed, and the stock lost 10% of its value. The general consensus was concern about the ongoing slowdown in profit growth, which decelerated even more last quarter — traditionally the quarter with the most growth:

The issue is costs, which have outgrown revenue for each of the last seven quarters:

To be perfectly honest, the slowdown in revenue growth was just as likely to be a factor in the stock’s slide, especially because Facebook’s costs have been growing so rapidly. Whatever the cause, if Zuckerberg’s only guiding principle is maximizing profits, he is extremely bad at it.

Facebook’s Security Investments

The fact of the matter is that Facebook, more than any other tech company, has put its money where its mouth is as far as security is concerned. Zuckerberg said on the company’s Q3 2017 earnings call:

I’ve directed our teams to invest so much in security on top of the other investments we’re making that it will significantly impact our profitability going forward, and I wanted our investors to hear that directly from me. I believe this will make our society stronger, and in doing so will be good for all of us over the long term. But I want to be clear about what our priority is. Protecting our community is more important than maximizing our profits.

Nine months later was when the growth rate of Facebook’s costs exceeded the growth rate of the company’s revenues for the first time, leading to the largest one-day loss by any company in U.S. stock market history; CFO Dave Wehner said on that 2Q 2018 earnings call:

Turning now to expenses; we continue to expect that full-year 2018 total expenses will grow in the range of 50% to 60% compared to last year…Looking beyond 2018, we anticipate that total expense growth will exceed revenue growth in 2019. Over the next several years, we would anticipate that our operating margins will trend towards the mid-30s on a percentage basis.

That is exactly what has happened.1 Facebook has spent on security (i.e. more people) more quickly than it has increased revenue — and it has increased revenue quite a bit! Vice President Andrew Bosworth expressed confidence in an internal memo2 that the money will prove to be well-spent; after noting that the role of foreign interference and misinformation on Facebook was extremely small relative to the content people saw over the last election cycle (a fair thing to note), Bosworth wrote:

Most of the information floating around that is widely believed isn’t accurate. But who cares? It is certainly true that we should have been more mindful of the role both paid and organic content played in democracy and been more protective of it. On foreign interference, Facebook has made material progress and while we may never be able to fully eliminate it I don’t expect it to be a major issue for 2020.

Misinformation was also real and related but not the same as Russian interference. The Russians may have used misinformation alongside real partisan messaging in their campaigns, but the primary source of misinformation was economically motivated. People with no political interest whatsoever realized they could drive traffic to ad-laden websites by creating fake headlines and did so to make money. These might be more adequately described as hoaxes that play on confirmation bias or conspiracy theory. In my opinion this is another area where the criticism is merited. This is also an area where we have made dramatic progress and don’t expect it to be a major issue for 2020.

Bosworth went on to note that President Trump ran a far superior digital advertising operation last campaign,3 and that he is worried that he will win in 2020 by doing the same. It is an admittedly self-serving but still crucial point to make: the effectiveness of Facebook’s expenditures should be based on the extent of illicit activity on Facebook, not the results of the next presidential election.

That, of course, is unlikely to happen, particularly if President Trump does indeed win re-election: Facebook will be almost certainly be held responsible because they are the easiest target, even if there is no meaningful foreign interference or disinformation campaigns. Critics will point to the company’s refusal to fact-check politicians, even if it is right on principle, and all of those expenses won’t make up for it.

Again, how is this profit-maximizing? If anything this is an argument for founder control: Facebook is spending billions of dollars and taking regular hits in the stock market for something they will almost certainly get no credit for, primarily because Zuckerberg believes it is the right thing to do.

That noted, Zuckerberg may not be entirely altruistic.

Facebook’s Missing Platform

At the beginning of the year I wrote The End of the Beginning, where I posited that the current tech giants would likely be dominant for some time to come:

There may not be a significant paradigm shift on the horizon, nor the associated generational change that goes with it. And, to the extent there are evolutions, it really does seem like the incumbents have insurmountable advantages: the hyperscalers in the cloud are best placed to handle the torrent of data from the Internet of Things, while new I/O devices like augmented reality, wearables, or voice are natural extensions of the phone.

In other words, today’s cloud and mobile companies — Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, and Google — may very well be the GM, Ford, and Chrysler of the 21st century. The beginning era of technology, where new challengers were started every year, has come to an end; however, that does not mean the impact of technology is somehow diminished: it in fact means the impact is only getting started.

Careful readers would have noted that I left out one of the tech giants — Facebook. The reason is straightforward: Facebook isn’t a platform, but rather an Aggregator. I explained the differences in A Framework for Regulating Competition on the Internet:

The name “platform” is a descriptive one: it is the foundation on which entire ecosystems are built. The most famous example of a platform — one with which regulators are intimately familiar — is Microsoft Windows. Windows provided an operating system for personal computers, a set of APIs for developers, and a user interface for end users, to the benefit of all three groups: developers could write applications that made personal computers useful to end users, thanks to the Windows platform tying everything together…

“Aggregator” is also descriptive: Aggregators collect a critical mass of users and leverage access to those users to extract value from suppliers. The best example of an Aggregator is Google. Google offered a genuine technological breakthrough with Google Search that made the abundance of the Internet accessible to users; as more and more users began their Internet sessions with Google, suppliers — in this case websites — competed to make their results more attractive to and better suited to Google, the better to acquire end users from Google, which made Google that much better and more attractive to end users.

This excerpt raises a fair question: why did I include Google as a foundational company and not Facebook if they are both Aggregators? Three reasons:

- Google controls the largest mobile platform in the world (Android).

- While Google Search is not essential to connecting users and websites, both users and websites behave as if it is, suggesting the sort of multi-sided network effects that are strong moats.

- Google has an ad platform that supports not only Google properties, but also YouTube and websites across the Internet.

This last point is a crucial one: the word “platform” tends to evoke developers, but Google plays the same role connecting consumers, advertisers, and websites (both its own and 3rd-party) that Windows played connecting users, developers, and OEMs.

Facebook, meanwhile, has always been much more of a closed garden. Its most important content comes not from 3rd-parties, but rather its own users. Similarly, its advertising uses Facebook data on Facebook properties. This self-containment helped protect Facebook from Google and made it into the giant that it is, but it is a fundamentally more fragile position than the other big tech companies.

This is also why investing in security is, in the long-run, not simply altruistic. Facebook depends on users using Facebook properties because they choose to use Facebook properties; Facebook connects advertisers to those users, the advertisers are not a reason to stay on the platform. Absent 3rd-parties that make Facebook essential, Facebook has to do whatever it takes to ensure users don’t leave the platform.

This is also why Facebook has invested so heavily in virtual and augmented reality. Zuckerberg knows the importance of platforms — remember, the entire reason Facebook ended up in the Cambridge Analytica scandal was in an attempt to make Facebook into a platform — and is betting that being early to the next paradigm will secure the company’s position.

In fact, though, Facebook has a much larger opportunity.

FAN’s Failed Promise

Facebook Audience Network is Facebook’s ad platform for 3rd-party mobile apps, mobile websites, and video. It quite obviously exists, but it definitely doesn’t seem to be getting much attention internally: the last time it was mentioned on an earnings call was in Q1 2018, and then only in a passing comment about increased transparency; the last substantive discussion was way back in Q2 2016.

It’s easy to figure out why: any company, even one the size of Facebook, has to choose what to spend resources on; doing one thing means not doing another. And, in a competition between Facebook’s own ad products and Facebook Audience Network, it was inevitable that Facebook Audience Network would lose:

- First and foremost, Facebook Audience Network ads have lower margins. That is because Facebook has to share revenue with the site or app that shows an ad.

- Secondly, Facebook Audience Network ads have lower revenues because the best ad units are on Facebook properties! Any advertiser, for the same price, would rather advertise in Facebook’s feed than on a 3rd-party app or site, because it performs better; that means the ads are never the same price.

- Third, the nature of digital advertising is such that Facebook has effectively unlimited inventory on its own properties, particularly with the explosion of Stories. That means the first two factors are always true.

You can see a similar dynamic at Google: DoubleClick, its 3rd-party advertising business, was an acquisition, not home-grown, and even still the percentage of revenue generated on Google’s own properties continues to grow. It’s hard to resist focusing efforts on the ad products that make more money with better margins!

Still, it is DoubleClick that, more than anything, makes Google into an ad platform. DoubleClick introduces a third stakeholder — 3rd party websites and apps — into the equation, making Google that much stickier and essential. This is exactly what Facebook should do with Audience Network.

Facebook’s Opportunity

The relative worth of investing in Facebook Audience Network relative to Facebook’s own ads will never change; there are, though, good reasons for Facebook to invest anyways.

First, privacy regulation like GDPR or California’s CCPA is much more challenging for 3rd-party advertising networks that rely on collecting user information across non-owned-and-operated sites than Facebook or Google. Facebook and Google already have superior targeting capabilities, and that advantage is only going to increase.

Second, Facebook’s data is much better for display advertising; Google is superior at identifying and capitalizing on purchase intent, particularly through search but also re-targeting, but Facebook excels at building brands and surfacing things you didn’t know you wanted. These categories are likely to be much more effective in most website or apps which are not necessarily about immediate conversions.

Third, the biggest reason to be bullish on Facebook is its dominance in digital advertising. As long as it has access to most customers, it will always be the default choice for advertisers; spending more time and attention on extending its advertising to 3rd-parties also extends the responsibility of attracting customers. Yes, this costs margin, but the payback is an even better moat.

The reason to bring this up now is the pressure Facebook is under, from PR to politics to the stock market:

- A meaningful investment in the Facebook Audience Network would mean lower margins in the long run, so best to make the investment when investors are already grumpy about margins.

- So much of the media only sees Facebook as a competitor; Facebook is uniquely placed to be their benefactor.

- The PR angle is not obvious, but I do think that Facebook in the long run is likely to be recognized as the company that has made the greatest investment in security. This will make regulators more comfortable with Facebook being one of the few companies constructed to leverage user data for advertising.

This article is not, by the way, my opinion on what is best for the world; rather, despite all of the company’s bad press, my point is that Facebook is better positioned for the future than it appears. More privacy regulation, more attention on security issues, more concerns about Google leveraging its own position: all of these are opportunities for Facebook. The question is if it will leverage investor discontent to make the sort of shift that gives up margin to build moats. Facebook can finally have its platform — the timing is right — if it is willing to take the risk.