Two months ago I bemoaned how Web 2.0 had failed to live up to its promise in one crucial area; from The Web’s Missing Interoperability:

[From] the Wikipedia…definition:

Web 2.0…refers to websites that emphasize user-generated content, ease of use, participatory culture and interoperability (i.e., compatible with other products, systems, and devices) for end users.

Seventeen years on and there is more user-generated content than ever, in part because it is so easy to generate: you can type an update on Facebook, post a photo on Instagram, make a video on TikTok, or have a conversation on Clubhouse. That, though, points to Web 2.0’s failure: interoperability is nowhere to be found.

The context for that piece was Twitter’s preview of Super Follows, acquisition of Revue, and imminent launch of Spaces, all of which helped explain how centralization had won the web. Twitter’s latest acquisition, though, leverages centralization in a way that bodes well for realizing the “thousand flowers bloom” vision of Web 2.0.

Web 2.0 and the Aggregators

The first page of O’Reilly’s definition of 2.0 had a “Web 2.0 Meme Map”:

Don’t worry about the low resolution and tiny type; what should feel familiar is this idea of an interlocking web of properties and services between which a user could flit to and fro, tying their content and data together with links. It turned out, though, that centralized services offered better user experiences that gained them critical masses of users, drawing suppliers onto the service on the service’s terms, attracting more users in a virtuous cycle; meanwhile, by virtue of being centralized, the service could gather better data about its users and offer a one-stop shop for advertisers. Aggregation Theory, in other words.

Aggregation was the antithesis of the Web 2.0 promise; the best suppliers could do was either subject themselves to the Aggregator’s terms and try and make the best of it (call it the BuzzFeed strategy) or work to build a direct connection with customers that went around the Aggregators (the New York Times strategy); Twitter, though, may be on the verge of offering a middle path: market-making.

Ad Agencies

Market-making in media isn’t a new concept; perhaps the best example is the traditional advertising agency. I explained back in 2017’s Ad Agencies and Accountability:

Few advertisers actually buy ads, at least not directly. Way back in 1841, Volney B. Palmer, the first ad agency, was opened in Philadelphia. In place of having to take out ads with multiple newspapers, an advertiser could deal directly with the ad agency, vastly simplifying the process of taking out ads. The ad agency, meanwhile, could leverage its relationships with all of those newspapers by serving multiple clients:

It’s a classic example of how being in the middle can be a really great business opportunity, and the utility of ad agencies only increased as more advertising formats like radio and TV became available. Particularly in the case of TV, advertisers not only needed to place ads, but also needed a lot more help in making ads; ad agencies invested in ad-making expertise because they could scale said expertise across multiple clients.

In this case the ad agencies gave a single point of contact for advertisers on one side, and ad inventory sellers on the other, creating a market.

That was then, though; aggregation has been terrible for ad agencies for the same reason it has been bad for publishers: the more that advertising becomes centralized on Facebook and Google, whether on their sites or on programmatic exchanges, the fewer advertising dollars are available for the inventory that ad agencies used to abstract away for clients. And, as I noted in that article:

That’s a problem for the ad agencies: when there are only two places an advertiser might want to buy ads, the fees paid to agencies to abstract complexity becomes a lot harder to justify.

In this world, the more effective of the two strategies I noted above has clearly been the New York Times model, at least for the New York Times and its 7.5 million subscribers; Visual Capitalist put together this striking infographic last week showing how the New York Times dominated the subscription market (click through to see a veritcal version of the infographic that shows every publication listed):

The problem is that there are a lot of publications in the world that would like to be supported by subscriptions, and a lot of readers in the world that would prefer to pay for ad-free content, but nobody is making a market. This is where Twitter is making its play.

Twitter Buys Scroll

From the Scroll blog:

Twitter is acquiring Scroll. The service will be going into private beta as we integrate into a broader Twitter subscription later in the year. We’re very excited!

Since launch last year, Scroll has proven that there’s a model that gives consumers a better experience and journalists a better future. Today when Scroll members visit hundreds of top sites like The Atlantic, The Verge, USA Today, The Sacramento Bee, The Philadelphia Inquirer or The Daily Beast, they get a site that feels built solely for them: a blazing fast experience that loads with no ads, no dodgy trackers and no chumboxes of clickbait. At the same time, publishers get to deliver a site that increases engagement and makes them more money than they would make from ads. It’s a better internet and we’ve proven the model works.

I’ve been a subscriber to Scroll for some time now, and it’s a great experience: while ad-blockers are oppositional to publishers, blocking their trackers and advertisements while users take content they refuse to help monetize, Scroll partnered with publications directly, such that Scroll subscribers were never served ads in the first place. Publishers would instead get paid their usage-based share of the Scroll user’s subscription fee, which Scroll claimed was more than a publication would have made by serving that user ads.

Scroll’s list of partner sites has been scrubbed from their website, but I recall it being pretty impressive; the real challenge for the startup, though, was acquiring users, which is the first reason why Twitter is a great match: Twitter not only has 199 million monetizable daily active users, but is also one of the places where users are most likely to click-through to publications.

Now imagine this model, but with Scroll’s business model on top:

This is a great example of market-making in action: Twitter is taking its user base, which no one publication could realistically reach or monetize on its own, and re-distributing their subscription fee across publications that no one user could ever support individually.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that every publication will buy in; the New York Times, to take an obvious example, is doing quite well on its own, as are sovereign writers. Twitter, though, because of its outsized role in driving traffic to sites across the web, is uniquely positioned to bundle everything else together. Moreover, there are, as they say levels to this: Twitter could offer one price tier for no ads, and another price tier for getting past paywalls, and perhaps even individual site subscriptions above that.

Multi-Medium Creators

Spotify’s announcement last week, meanwhile, shows that markets need not be exclusive. Start with creators: today someone might build a following on Instagram, before branching out to YouTube or TikTok, much as an artist may have started out singing and ended up making movies. Today this ability to move across mediums extends down to even the smallest creators: even Stratechery is multi-medium, with text available on the web or via email, and podcasts on your phone.

What is new is that the business model can be more than fame (and, naturally, advertising). Subscriptions work for creators just as well as they do for publications (arguably better given an individual creator’s cost structure), but to-date that has meant that creators were limited to mediums that they could fully control — i.e. text and podcasts — and only on the open web; what Spotify made clear is that they want into this world. From Spotify’s Surprise:

For full disclosure, I have been briefed on the Open Access Platform, and Spotify has addressed all of my concerns; no, they won’t support arbitrary RSS feeds, but instead another open technology — OAuth. Some time soon Stratechery and Dithering subscribers will be able to link their subscriptions to their Spotify accounts, and Spotify isn’t going to charge a dime — they will be my customers from email address to credit card. Spotify Chief R&D Officer Gustav Söderström told me, “Having all of audio on Spotify means meeting independent creators on their terms, not ours.”

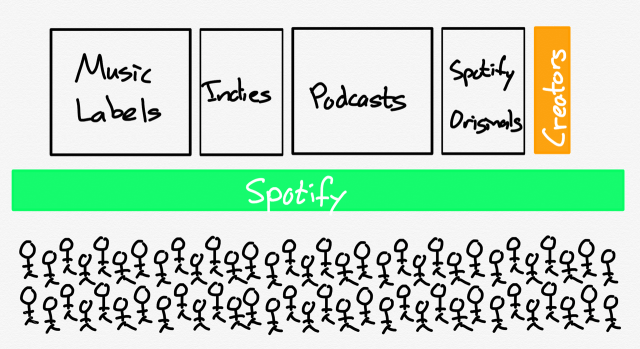

In this case Spotify isn’t market-making: rather, it is recognizing that creators are going to want to make their own markets, pulling their fans from medium to medium and service to service, and they want to make sure they are plugged in to that:

What is neat about markets is that they create the conditions for win-win outcomes; Spotify aligning with creators doesn’t hurt Spotify’s core business, it enhances it by making sure Spotify’s podcast service is as complete as it can be. Critically, it does this not by fighting over users, but rather by linking them.

This is the part that Web 2.0 got wrong; much like the Facebook model of social networking emphasized being your whole self, Web 2.0 assumed that your one identity would connect together the different pieces of your web existence. However, just as the future of social networking is about different identities for different contexts, interoperability via markets is about linking together distinct user bases in a way that is appropriate for different services, all under the control of the user who is paying for the privilege.

Shopify and Platforms

The other place where market-making might seem familiar is that most classic of tech concepts: platforms. I wrote in 2019’s Shopify and the Power of Platforms, in the context of the e-commerce service’s planned foray into logistics:

Notice, though, that Shopify is not doing everything on their own: there is an entire world of third-party logistics companies (known as “3PLs”) that offer warehousing and shipping services. What Shopify is doing is what platforms do best: act as an interface between two modularized pieces of a value chain.

On one side are all of Shopify’s hundreds of thousands of merchants: interfacing with all of them on an individual basis is not scalable for those 3PL companies; now, though, they only need to interface with Shopify.

The same benefit applies in the opposite direction: merchants don’t have the means to negotiate with multiple 3PLs such that their inventory is optimally placed to offer fast and inexpensive delivery to customers; worse, the small-scale sellers I discussed above often can’t even get an audience with these logistics companies. Now, though, Shopify customers need only interface with Shopify.

What makes the Shopify platform so fascinating is that over time more and more of the e-commerce it enables happens somewhere other than a Shopify website. Shopify, for example, can help you sell on Amazon, and in what will be an increasingly important channel, Facebook Shops. In the latter case Facebook and Shopify are partnering to create a fully-integrated market: Facebook’s userbase and advertising tools on one side, and Shopify’s e-commerce management and seller base on the other. The broader takeaway, though, is that Shopify’s real value proposition is working across markets, not creating an exclusive one.

Market-Making and Aggregators

Market-making is certainly a characteristic of Aggregators; Google, for example, is a one-stop shop for users, advertisers, and content suppliers. What makes Aggregators unique, though, is their infinite scalability, driven by the effectively zero marginal and transactional costs necessary to serve one more user, advertiser, or supplier. This characteristic, by necessity, reduces everything to a commodity. In contrast, the commonality between what Twitter appears to be building, the phenomenon that Spotify is seeking to plug into, and Shopify and e-commerce is the inherent friction of transferring money (usually via Stripe), for something that is not flattened, but differentiated.

Some of these plays are certainly more Aggregator-like — Twitter/Scroll appears likely to (non-exclusively) abstract away publishers from subscribers — but I think the distinction from advertiser-driven Super Aggregators is a notable development, and an exciting one. The web started with no economy, then built a commoditized advertising-only one, and now is increasingly a market for all sorts of goods and services — the more differentiated the better. That doesn’t just mean interoperability, in the purest most fungible form of money, but also opportunity.