There has been a bit of controversy around Substack over the last week; I’m not going to get into the specifics of various accusations made about various individuals, or their responses; however, I do think that there are a few fundamental issues about the Substack model specifically, and the shift to sovereign writers generally, that are being misunderstood.

I’m going to anchor on this piece from Peter Kafka at Recode:

Substack’s main business model is straightforward. It lets newsletter writers sell subscriptions to their work, and it takes 10 percent of any revenue the writers generate (writers also have to fork over another 3 percent to Stripe, the digital payments company)…

The money that Substack and its writers are generating — and how that money is split up and distributed — is of intense interest to media makers and observers, for obvious reasons. But the general thrust isn’t any different from other digital media platforms we’ve seen over the last 15 years or so.

From YouTube to Facebook to Snapchat to TikTok, big tech companies have long been trying to figure out ways they can convince people and publishers to make content for them without having to hire them as full-time content creators. That often involves cash: YouTube set the template in 2007, when it set up a system that let some video makers keep 55 percent of any ad revenue their clips generated…Like Substack, YouTube and the other big consumer tech sites fundamentally think of themselves as platforms: software set up to let users distribute their own content to as many people as possible, with as little friction as possible.

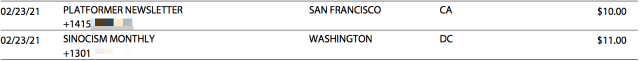

I’m not sure the connection to Facebook and YouTube hold (even with Substack Pro, which I’ll get to in a moment); As Kafka notes, Substack “lets newsletter writers sell subscriptions to their work”; that, by definition, means that Substack is not “figur[ing] out ways they can convince people and publishers to make content for them without having to hire them as full-time content creators”. Just look at my credit card statement, where I happened to find charges for Casey Newton’s Platformer and Bill Bishop’s Sinocism next to each other:

Notice that the names of the merchant, the phone number of the merchant, and the location are different — that’s because they are different merchants. Substack is a tool for Newton and Bishop to run their own business, no different than, say, mine; Kafka writes:

To be clear: You don’t need to work with a company like Substack or Ghost to create and sell your own newsletter. Ben Thompson, the business and technology writer whose successful newsletter served as the inspiration for Substack, built his own infrastructure cobbling together several services; my former colleague Dan Frommer does the same thing for his New Consumer newsletter. And Jessica Lessin, the CEO of the Information, told me on the Recode Media podcast that she’d consider letting writers use the paid newsletter tech her company has built for free.

Here’s what you see on your credit card statement for Stratechery:

![]()

My particular flavor of membership management software is Memberful, but Memberful is not Stratechery’s publisher; I am. Memberful is a tool I happen to use to run my business, but it has no ownership of or responsibility for what I write. Moreover, Memberful — like Substack — doesn’t hold my customer’s billing data; Stripe does, and that charge is from my Stripe account, just as the first two charges are from Newton and Bishop’s respective Stripe accounts.

This is what makes “the intent interest of media makers and observers” so baffling. There is a very easy and obvious answer to “how that money is split up and distributed”: subscriber money goes to the person or publication the subscriber subscribes to. That’s it! Substack is a tool for the sovereign writer; the sovereign writer is not a Substack employee, creator, contractor, nothing. Users quite literally pay writers directly, who pass on 10% to Substack; Substack doesn’t get any other say in “how that money is split up and distributed.”

But what about Substack Pro?

Substack Pro

Back in 2017 I wrote a post called Books and Blogs that explained why subscriptions were a much better model for writers than books:

A book, at least a successful one, has a great business model: spend a lot of time and effort writing, editing, and revising it up front, and then make money selling as many identical copies as you can. The more you sell the more you profit, because the work has already been done. Of course if you are successful, the pressure is immense to write another; the payoff, though, is usually greater as well: it is much easier to sell to customers you have already sold to before than it is to find customers for the very first time…

Since then it has been an incredible journey, especially intellectually: instead of writing with a final goal in mind — a manuscript that can be printed at scale — Stratechery has become in many respects a journal of my own attempts to understand technology specifically and the way in which it is changing every aspect of society broadly. And, it turns, out, the business model is even better: instead of taking on the risk of writing a book with the hope of one-time payment from customers at the end, Stratechery subscribers fund that intellectual exploration directly and on an ongoing basis; all they ask is that I send them my journals of said exploration every day in email form.

Recurring revenue is much better than selling a book once; however, just as you have to spend time to write a book before you can sell it, you need time to build up a subscriber base that supports a full-time subscription. I accomplished this by writing Stratechery on nights and weekends while working at Microsoft and Automattic, and then, when I started charging, basically jumping off of the deep end, but working writers can’t always do the former (I would bet that publications start being stricter about this going forward). This is where Substack Pro comes in; from Kafka:

But in some cases, Substack has also shelled out one-off payments to help convince some writers to become Substack writers, and in some cases those deals are significant. Yglesias says that when it lured him to the platform last fall, Substack agreed to pay him $250,000 along with 15 percent of any subscription revenue he generates; after a year, Yglesias’s take will increase to 90 percent of his revenue, but he won’t get any additional payouts from Substack.

As Yglesias told me via Slack (he stopped working as a Vox writer last fall but still contributes to Vox’s Weeds podcast), the deal he took from Substack is actually costing him money, for now. Yglesias says he has around 9,800 paying subscribers, which might generate around $860,000 a year. Had he not taken the Substack payment, he would keep 90 percent of that, or $775,000, but under the current deal, where he’ll keep the $250,000 plus 15 percent of the gross subscription revenue, his take will be closer to $380,000.

Substack has been experimenting with this kind of offer for some time, but last week, it began officially describing them as “Substack Pro” deals.

In short, the best analogy to Substack Pro are book advances, which are definitely something that publishers do. In that case publishers give an author a negotiated amount of money in advance of writing a book for reasons that can vary; in the case of famous people the advance represents the outcome of a bidding war for what is likely to be a hit, while for a new or unknown author an advance provides for the author’s livelihood while they actually write the book. The publisher then keeps all of the proceeds of the book until the advance is paid back, and splits additional proceeds with the author, usually in an 85/15 split (sound familiar?); of course we don’t know the exact details of book deals, because they are not disclosed.1

At the same time, Substack Pro isn’t like a book advance at all in a way that is much more advantageous to the writer. Book publishers own the publishing rights and control the royalties as long as it is in print; writers in the Substack Pro program still own their customers and all of the revenue past the first year, of which they can give 10% to Substack for continued use of their tool, or switch to another tool. This is where the comparison to YouTube et al falls flat: YouTube wants to be permanently in the middle of the creator-viewer relationship, while Substack remains to the side; from this perspective Substack Pro is more akin to an unsecured bank loan — success or failure is still determined by the readers.

The Real Scam

Now granted, there may be some number of Substack Pro participants who end up earning less than their advance, particularly if Substack sees Substack Pro as more of a marketing tool to shape who uses Substack; if Substack actually runs Substack Pro like a business, though, I would expect lots of deals like the Yglesias one, which has turned out to be quite profitable for Substack. As Yglesias himself noted:

And it was.

Substack is making money off of Slow Boring. More money in fact than they would have made without the deal.

But that’s what made it a good deal. They needed upside growth more than I did and I needed to minimize downside risk more than they did.

Business!

— Matthew Yglesias (@mattyglesias) March 18, 2021

Substack Pro made it possible for Yglesias to launch Slow Boring without worrying about paying the bills, and is making a profit as a reward for bearing the risk of Yglesias not succeeding or succeeding more slowly than he needed. As for Yglesias, he may end up missing out on several hundred thousand dollars this year, but given he’s not selling a book but rather a subscription he can look forward to a huge increase in revenue next year.

This, needless to say, is not a scam, which is what Annalee Newitz argued:

For all we know, every single one of Substack’s top newsletters is supported by money from Substack. Until Substack reveals who exactly is on its payroll, its promises that anyone can make money on a newsletter are tainted. We don’t have enough data to judge whether to invest our creative energies in Substack because the company is putting its thumb on the scale by, in Hamish’s own words, giving a secret group of “financially constrained writers the ability to start building a sustainable enterprise.” We are, not to put too fine a point on it, being scammed.

It is, for the reasons I laid out above, easier to get started with a subscription business if you have an advance. No question. But this take is otherwise completely nonsensical: Substack’s top newsletters are at the top because they have the most subscribers paying the authors directly. For example, look at the “Politics” leaderboard, where Yglesias is seventh:

We already know that “Thousands of Subscribers” to Slow Boring is 9,800; given that 9,800 * $8/month = $78,400/month, we can surmise that The Weekly Dish has at least 15,680 subscribers ($78,400/month ÷ $5/month). Those are real people paying real dollars of their own volition, not because Substack is somehow magically making them do it.

Frankly, it’s hard to shake the sense that Newitz and other Substack critics simply find it hard to believe that there is actually a market for independent writers, which I can understand: I had lots of folks tell me Stratechery was a stupid idea that would never work, but the beautiful thing about being my own boss is that they don’t determine my success; my subscribers do, just as they do every author on Substack.

Still, that doesn’t change the fact there is a real unfair deal in publishing, and it has nothing to do with Substack. Go back to Yglesias: while I don’t know what he was paid by Vox (it turns out that Substack, thanks to their leaderboards, is actually far more transparent about writers’ income than nearly anywhere else), I’m guessing it was a lot less than the $380,000 he is on pace for, much less the $775,000 he would earn had he forgone an advance.2 It was Vox, in other words, that was taking advantage of Yglesias.

This overstates things, to be sure; while Yglesias built his following on his own, starting with his own blog in 2002, Vox, which Yglesias co-founded, was a team effort, including capital from Vox Media. Still, if we accept the fact that Yglesias charging readers directly is the best measurement of the value those readers ascribe to his writing, then by definition he was severely under-compensated by Vox. The same story applies to Andrew Sullivan, the author of the aforementioned The Weekly Dish; Ben Smith reported:

But Mr. Sullivan is, as his friend Johann Hari once wrote, “happiest at war with his own side,” and in the Trump era, he increasingly used the weekly column he began writing in New York magazine in 2016 to dial up criticism of the American left. When the magazine politely showed him the door last month, Mr. Sullivan left legacy media entirely and began charging his fans directly to read his column through the newsletter platform Substack, increasingly a home for star writers who strike out on their own. He was not, he emphasizes, “canceled.” In fact, he said, his income has risen from less than $200,000 to around $500,000 as a result of the move.

Make that nearly $1 million, i.e. $800,000 of surplus value that New York Magazine showed the door.

Substack Realities

Of course things aren’t so simple; Sullivan, like several of the other names on that leaderboard, are, to put it gently, controversial. That he along with other lightning-rod writers ended up on Substack is more a matter of where else would they go? Again, the entire point is that Sullivan’s readers are paying Sullivan, which means Substack was an attractive option precisely because they don’t decide who gets paid what — or if they get paid at all.

Just because Sullivan was forced to be a sovereign writer, though, doesn’t change the fact that writers who can command a paying audience have heretofore been significantly underpaid. That points to the real reason why the media has reason to fear Substack: it’s not that Substack will compete with existing publications for their best writers, but rather that Substack makes it easy for the best writers to discover their actual market value.

This is where Substack really is comparable to Facebook and the other big tech companies; the media’s revenue problems are a function of the Internet unbundling editorial and advertising. The fact that Google and Facebook now make a lot of money from advertising is unrelated. Similarly, media’s impending cost problem — as in they will no longer be able to afford writers that can command a paying audience — is a function of the Internet making it possible to go direct; that Substack is one of many tools competing to make this easier will be similarly unrelated.

This explains three other Substack realities:

- First, Substack is going to have a serious problem retaining its most profitable writers unless it substantially reduces its 10% take.

- Second, Substack is less threatened by Twitter and Facebook than many think; the problem with the social networks is that they want to own the reader, but the entire point of the sovereign writer is that they own their audience. Substack’s real threat will be lower-priced competitors.

- Third, it would be suicidal for Substack to kick any successful writers off of its platform for anything other than gross violations of the law or its terms of service. That would be a signal for every successful writer to seek out a platform that is not just cheaper, but also freer (i.e. open-source).

This is also why Substack Pro is a good idea. To be honest, I was a tad bit generous above: signing up someone like Yglesias is closer to the “popular author bidding war” side of the spectrum, and may not be worth the trouble; what would be truly valuable is helping the next great writer build a business, perhaps in exchange for more lock-in or the rights to bundle their work. Ideally these writers would be the sort of folks who would have never gotten a shot in traditional media, because they don’t fit the profile of a typical person in media, and/or want to cover a niche that no one has ever thought to cover (these are almost certainly related).

The Sovereign Writer

I am by no means an impartial observer here; obviously I believe in the viability of the sovereign writer. I would also like to believe that Stratechery is an example of how this model can make for a better world: I went the independent publishing route because I had no other choice (believe me, I tried).

At the same time, I suspect we have only begun to appreciate how destructive this new reality will be for many media organizations. Sovereign writers, particularly those focused on analysis and opinion, depend on journalists actually reporting the news. This second unbundling, though, will divert more and more revenue to the former at the expense of the latter. Maybe one day Substack, if it succeeds, might be the steward of a Substack Journalism program that offers a way for opinion writers and analysts to support those that undergird their work.3

What is important to understand, though, is that Substack is not in control of this process. The sovereign writer is another product of the Internet, and Substack will succeed to the extent it serves their interests, and be discarded if it does not.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

Substack reportedly pays 15% of all revenue, not just revenue above-and-beyond the advance. ↩

There is an anonymous Google Doc with self-reported media salaries; only three individuals make more than $380,000, and none more than $775,000 ↩

I am still bullish on the Local News Business Model. ↩