If there is one industry people in tech are eternally certain is doomed, it is cable. However, the reality is that cable is both stronger than ever and poised for growth; the reasons why are instructive to not just tech industry observers, but to tech companies themselves.

The Creation of Cable

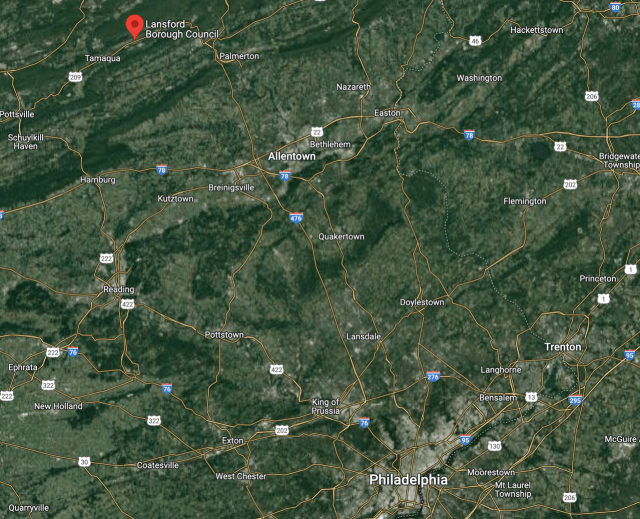

Robert J. Tarlton was 29 years old, married with a son, when he volunteered to fight in World War II; thanks to the fact he owned a shop in Lansford, Pennsylvania that sold radios, he ended up repairing them all across the European Theater, learning about not just reception but also transmission. After the war Tarlton re-opened his shop, when Motorola, one of his primary suppliers, came out with a new television.

Tarlton was intrigued, but he had a geography problem; the nearest television station was in Philadelphia, 71 miles away; in the middle lie the Pocono Mountains, and mountains aren’t good for reception:

It turned out, though, that some people living in Summit Hill, the next community over, could get the Philadelphia broadcast signal; that’s where Tarlton sold his first television sets. Of course Tarlton couldn’t demonstrate this new-fangled contraption; his shop was in Lansford, not Summit Hill. However, it was close to Summit Hill: what if Tarlton could place an antenna further up the mountain in Summit Hill and run a cable to his shop? Tarlton explained in an interview in 1986:

Lansford is an elongated town. It’s about a mile and a half long and there are about eight parallel streets bisected with cross streets about every 500 feet. There are no curves; everything is all laid out in a nice symmetrical pattern. Our business place was about three streets from the edge of Summit Hill and Lansford sits on kind of a slope. The edge of Lansford inclines from about a thousand feet above sea level to about fifteen hundred feet above sea level in Summit Hill. So to get television into our store, my father and I put an antenna partly up the mountain. No, we didn’t go all the way up, but we put up an antenna, kind of a crude arrangement, and then from tree to tree we strung a twin lead that was used in those days as a transmission line. We ran this twin lead, crossed a few streets, and into our store. And we had television.

The basic twin lead was barely functional, but that didn’t stop everyone from demanding a television with a haphazard wire to their house; Tarlton realized that new coaxial cable amplifiers designed for a single property could be chained together, re-amplifying the signal so it could reach multiple properties. After getting all of the other electronics retailers on board — Tarlton knew that a clear signal would sell more TV sets, but that everyone needed to use the same system — the first commercial cable system was born, and it sold itself. Tarlton reflected:

You didn’t have to advertise. You had to keep your door locked because the people were clamoring for service. They wanted cable service. You certainly didn’t have to advertise.

People couldn’t get enough TV; Tarlton explained:

Cable is dependent upon advances in technology because people who originally saw one channel wanted to see the second channel, wanted to see the third, and after you had five, they wanted more. So it was a case of more begets more. At one time three channels seemed to be quite sufficient but when we added one more channel, it created a new interest in the cable system. People then had variety. They had alternatives. At one time later five channels seemed enough. As a matter of fact, a man who is often quoted, former FCC Commissioner Ken Cox, said that five channels was enough, and that’s quite a story in itself. The engineers were able to continually refine equipment to add more channels…All these technical advances‑‑continuing advances, automatic gain control, automatic temperature compensation, etc. have made cable what it is today.

One of the most important technological developments was satellite: now cable systems could get signals both more reliably and from far further away; this actually flipped geography on its head. Tarlton said:

At that time we went to the highest possible point to look to the transmitter. Today with satellites, we go to the lowest possible point because we don’t want the interference from other signals. So it is ironic that we have changed so much from what we used to do.

Within these snippets is everything that makes the cable business so compelling:

- Cable is in high demand because it provides the means to get what customers most highly value.

- Cable works best both technologically and financially when it has a geographic monopoly.

- Cable creates demand for new supply; technological advances enable more supply, which creates more demand.

It’s that last bit about satellites being better on lower ground that stands out to me, though: as long as you control the wires into people’s houses you can and should be pragmatic about everything else.

Cable’s Evolution

Tarlton would go on to work for a company called Jerrold Electronics, which pivoted its entire business to create equipment for cities that wanted to emulate Lansford’s system; Tarlton would lead the installation of cable systems across the United States, which for the first two decades of cable mostly retransmitted broadcast television.

The aforementioned satellite, though, led to the creation of national TV stations, first HBO, and then WTCG, an independent television station in Atlanta, Georgia, owned by Ted Turner. Turner realized he could buy programming at local rates, but sell advertising at national rates via cable operators eager to feed their customers’ hunger for more stations. Turner soon launched a cable only channel devoted to nothing but news; he called it the Cable News Network — CNN for short (WTCG would later be renamed TBS).

Jerrold Electronics, meanwhile, spun off one of the cable systems it built in Tupelo, Mississippi to an entrepreneur named Ralph Roberts; Roberts proceeded to systematically buy up community cable systems across the country, moving the company’s headquarters to Philadelphia and renaming it to Comcast Corporation (Roberts would eventually hand the business off to his son, Brian). Consolidation in the provision of cable service proceeded in conjunction with consolidation in the production of content, an inevitable outcome of the virtuous cycle I noted above:

- Cable companies acquired customers who wanted access to content

- Studios created content that customers demanded

The more customers that a cable company served, the stronger their negotiating position with content providers; the more studios and types of content that a content provider controlled the stronger their negotiating position with cable providers. The end result were a few dominant cable providers (Comcast, Charter, Cox, Altice, Mediacom) and a few dominant content companies (Disney, Viacom, NBC Universal, Time Warner, Fox), tussling back-and-forth over a very profitable pie.

Then came Netflix, and tech industry crowing about cord cutting.

Netflix and other streaming services were obviously bad for television: they did the same job but in a completely different way, leveraging the Internet to provide content on-demand, unconstrained by the linear nature of television that was a relic of cable’s origin with broadcast TV. Here, though, cable’s ownership of the wires was an effective hedge: the same wires that delivered linear TV delivered packet-based Internet content.

Moreover, this didn’t simply mean that cable’s TV losses were made up for by Internet service: Internet service was much higher margin because companies like Comcast didn’t need to negotiate with a limited number of content providers; everything on the Internet was free. This has meant that the fortunes of cable companies has boomed over the last decade, even as cord-cutting has cut the cable TV business by about a third.

Cable companies today, though, are yet another category down from their pandemic highs, thanks to fear that the broadband growth story is mostly over; fiber offers better performance, 5G opens the door to wireless in the home, and anyone who doesn’t have broadband now is probably never going to get it. I think, though, this underrates the strategic positioning of cable companies, and ignores the industry’s demonstrated ability to adapt to new strategic environments.

The Wireless Opportunity

From the Wall Street Journal in 2011:

Verizon Wireless will pay $3.6 billion to buy wireless spectrum licenses from a group of cable-television companies, bringing an end to their years-long flirtation with setting up its own cellphone service. The sellers—Comcast Time Warner Cable Inc. and Bright House Networks—acquired the spectrum in a government auction in 2006 and now will turn it over to the country’s biggest wireless carrier at more than a 50% markup. While cable companies have dabbled with wireless, the spectrum has largely sat around unused, prompting years of speculation about the industry’s intentions…

Under the deal, Verizon Wireless will be able to sell its service in the cable companies’ stores. The carrier, in turn, will be able to sell the cable companies’ broadband, video and voice services in its stores. Verizon’s FiOS service only reaches 14% of U.S. households, according to Bernstein Research. In four years’ time, the cable companies will have the option to buy service on Verizon’s network on a wholesale basis and then resell it under their own brand.

The joint marketing arrangement “amounts to a partnership between formerly mortal enemies,” wrote Bernstein analyst Craig Moffett in a research note.

Moffett would later partner with Michael Nathanson to form their own independent research firm (called MoffettNathanson, natch); Moffett released an updated report last month that explained how that Verizon deal ended up playing out:

When Comcast and Time Warner Cable sold their AWS-1 spectrum to Verizon back in 2011, they believed at the time that they were walking away from ever becoming facilities-based wireless players. They therefore viewed it as imperative that the sale come with an MVNO agreement with Verizon to compensate for that forfeiture. They got precisely what they wanted, an MVNO contract with Verizon that was described at the time as “perpetual and irrevocable“…

It took another six years after that transaction before Comcast finally launched Xfinity Mobile in mid-2017. Charter [which merged with Time Warner Cable, acquiring the latter’s MVNO rights] followed suit a year later…in four short years, the Cable operators have become the fastest growing wireless providers in the country, accounting for nearly 30% of wireless industry net additions. Cable’s 7.7 million mobile lines represent ~2.5% of the U.S. mobile phone market (including prepaid and postpaid phones).

As Moffett notes, this growth is particularly impressive given that most cable companies couldn’t feasibly offer family plans under the terms of the original deal, which was negotiated before such a concept even existed; the deal has been re-negotiated, though, and almost certainly to the cable companies’ advantage: if Verizon is going to lose customers to an MVNO, it would surely prefer said MVNO be on their network; this means that the cable companies have negotiating leverage.

What, though, makes the cable companies such effective MVNOs? One of the most interesting parts of Moffett’s note was proprietary data about the amount of data used by cellular subscribers; it turns out that cable MVNO customers are far more likely to consume data over WiFi, perhaps because of cable company out-of-home WiFi hot spots. This could become even more favorable in the future as cable companies build out Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) service, particularly in dense areas where cable companies have wires from which to hang CBRS transmitters. Moffett writes:

In a perfect world, Cable will offload traffic onto their own facilities where doing so is cheap (high density, high use locations) and leave to Verizon the burden of carrying traffic where doing so is/would be expensive. Because the MVNO agreement is “perpetual and irrevocable,” and is based on average prices (i.e., the same price everywhere, whether easy or hard to reach), Cable is presented with a perfect ROI arbitrage; they can take the high ROI parts of the network for themselves, and leave the low ROI parts of the network to their MVNO host… all without sacrificing anything with respect to their national coverage footprint.

One can understand why Verizon gave the cable companies these rights in 2011; the phone company desperately needed spectrum, and besides, everyone knew that MVNOs could never be economically competitive with their wholesale providers, who were the ones that actually made the investments in the network.

That’s the thing, though: cable companies had their own massive build-out, one that was both much older in its origins and, because it connected the house, actually carried more data. This was to the benefit of Verizon and other cellular providers, of course: a Verizon iPhone uses WiFi at home just as much as a Comcast iPhone does; here, though, it was cable that had internet economics on its side: there is no competitive harm in giving equal access to an abundant resource; it is cellular access that is scarce, which means that the cable companies’ MVNO deal, in conjunction with their out-of-home Internet access options, gives them a meaningful advantage.

Customer Acquisition

Moffett spends less time on customer acquisition; anecdotally speaking, it’s clear that Charter’s Spectrum, which provides the cable service I consume (via the excellent Channels application), is pushing wireless service hard: phones are front-and-center in their stores, and Spectrum wireless commercials fill local inventory. Moreover, this is a well-trodden playbook: cable companies came to dominate the fixed line phone service business simply because it was easier to get your TV, Internet, and phone all in the same place (and of those, the most important was TV, and now Internet); it’s always easier to upsell an existing subscriber than it is to acquire a new one.

Of course cable companies long handled customer acquisition for content creators — that was the cable bundle in a nutshell. What is interesting is how this customer acquisition capability is attractive to the companies undoing that bundle: Netflix, for example, put its service on Comcast’s set-top boxes in 2016, and made a deal for Comcast to sell its service in 2018. I wrote in a Daily Update at the time:

Netflix, meanwhile, is laddering up again: the company doesn’t actually need a billing relationship with end users, it just needs ever more end users (along with the data about what they watch) to spread its fixed content costs more widely; the company said in its shareholder letter that:

These relationships allow our partners to attract more customers and to upsell existing subscribers to higher ARPU packages, while we benefit from more reach, awareness and often, less friction in the signup and payment process. We believe that the lower churn in these bundles offsets the lower Netflix ASP.

What is particularly interesting is that this arrangement moves the industry closer to the endgame I predicted in The Great Unbundling…

“Endgame” was a bit strong: that Article was, as the title says, about unbundling; one of my arguments was that the traditional cable TV bundle would become primarily anchored on live sports and news, while most scripted content went to streaming. That is very much the case today (TBS, for example, is abandoning scripted content, while becoming ever more reliant on sports). What was a mistake was insinuating that this was the “end”; after all, as Jim Barksdale famously observed, the next step after unbundling is bundling.

To that end, Netflix + Xfinity TV service was a bundle of sorts, but the real takeaway was that Comcast was fine with being simply an Internet provider (which ended up helping with TV margins, since cable companies mostly gave up on fighting to keep cord cutters). Shortly after the Netflix deal Comcast launched Xfinity Flex, a free 4K streaming box for Internet-only subscribers that included a storefront for buying streaming services (which would be billed by Comcast). You can even subscribe to digital MVPDs like YouTube TV!

The first takeaway of an offering like Xfinity Flex ties into the wireless point: cable companies already have a billing relationship with the customer — because they provide the most essential utility for accessing what is most important to said customer — which makes them particularly effective at customer acquisition. That is why Netflix, YouTube, etc. are all willing to pay a revenue share for the help.

The Great Rebundling?

The second takeaway, though, is that the cable companies are better suited than almost anyone else to rebundle for real. Imagine a “streaming bundle” that includes Netflix, HBO Max, Disney+, Paramount+, Peacock, etc., available for a price that is less than the sum of its parts. Sounds too good to be true, right? After all, this kind of sounds like what Apple was envisioning for Apple TV (the app) before Netflix spoiled the fun; I wrote in Apple Should Buy Netflix in 2016:

Apple’s desire to be “the one place to access all of your television” implies the demotion of Netflix to just another content provider, right alongside its rival HBO and the far more desperate networks who lack any sort of customer relationship at all. It is directly counter to the strategy that has gotten Netflix this far — owning the customer relationship by delivering a superior customer experience — and while Apple may wish to pursue the same strategy, the company has no leverage to do so. Not only is the Apple TV just another black box that connects to your TV (that is also the most expensive), it also, conveniently for Netflix, has a (relatively) open app platform: Netflix can deliver their content on their terms on Apple’s hardware, and there isn’t much Apple can do about it.

Six years on and Netflix is in a much different place, not only struggling for new customers but also dealing with elevated churn. Owning the customer may be less important than simply having more customers, particularly if those customers are much less likely to churn. After all, that’s one of the advantages of a bundle: instead of your streaming service needing to produce compelling content every single month, you can work as a team to keep customers on board with the bundle.

The key point about a bundle, as longtime YouTube executive and Coda CEO Shishir Mehrotra has written, is that it minimizes SuperFan overlap while maximizing CasualFan overlap; in other words, effective bundles have more disparate content that you are vaguely interested in, instead of a relatively small amount of focused content that you care about intensely. This makes the bundle concept even more compelling to new entrants in the streaming wars, who may not have as large of libraries as Netflix, and certainly don’t have as many subscribers over which to spread their content costs.

Moreover, the fact that the streaming services have largely done their damage to traditional TV, leaving the cable TV bundle as the sports and news bundle, means it is actually viable to create a lower-priced bundle than what was previously available (if you don’t want sports). After all, you’re not cannibalizing TV, but rather bringing together what has long since been broken off (unbundling then bundling!).

This isn’t something that is going to happen overnight: despite the fact that bundles are good for everyone it is hard to get independents into a bundle as long as they are growing; Netflix’s recent struggles are encouraging in this regard, particularly if other streaming services start to face similar headwinds. Moreover, cable companies are not the only entities that will seek to pull something like this off: Apple, Amazon, Google, and Roku already make money from revenue shares on streaming subscriptions they sell; all of them sell devices that can be used as interfaces for selling a bundle. And, of course, there are more Internet providers than just the cable companies: there is fiber, wireless, and even Starlink.

The breadth of the cable company bundle, though, is unmatched: not only might it include streaming services, but also linear TV; more than that, this is the company selling you Internet access, and increasingly wireless phone service. That gives even more latitude for discounts, and perks like no data caps on streamed content, not just at home but also on your phone.

All of these advantages go back to Robert J. Tarlton and Lansford, Pennsylvania. A recurring point on Stratechery this past year has been the durability and long-term potential inherent in technology rooted in physical space. I wrote in Digital Advertising in 2022:

Real power in technology comes from rooting the digital in something physical: for Amazon that is its fulfillment centers and logistics on the e-commerce side, and its data centers on the cloud side. For Microsoft it is its data centers and its global sales organization and multi-year relationships with basically every enterprise on earth. For Apple it is the iPhone, and for Google is is Android and its mutually beneficial relationship with Apple (this is less secure than Android, but that is why Google is paying an estimated $15 billion annually — and growing — to keep its position). Facebook benefited tremendously from being just an app, but the freedom of movement that entailed meant taking a dependency on iOS and Android, and Apple has exploited that dependency in part, if not yet in full.

For cable companies, power comes from a wire; it would certainly be ironic if the cord-cutting trumpeted by tech resulted in cable having even more leverage over customers and their wallets than the pre-Internet era.