Apple released the Vision Pro on February 2; 12 days later Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg delivered his verdict:

Alright guys, so I finally tried Apple’s Vision Pro. And you know, I have to say that before this, I expected that Quest would be the better value for most people since it’s really good and it’s like seven times less expensive. But after using it I don’t just think that Quest is the better value — I think the Quest is the better product, period.

You can watch the video for Zuckerberg’s full — and certainly biased! — take, but the pertinent section for this Article came towards the end:

The reality is that every generation of computing has an open and a closed model, and yeah, in mobile, Apple’s closed model won. But it’s not always that way. If you go back to the PC era, Microsoft’s open model was the winner, and in this next generation, Meta is going to be the open model, and I really want to make sure that the open model wins out again. The future is not yet written.

John Gruber asked on Daring Fireball:

At the end, he makes the case that each new generation of computing devices has an open alternative and a closed one from Apple. (It’s interesting to think that these rivalries might be best thought of not as closed-vs.-open, but as Apple-vs.-the-rest-of-the-industry.) I’m not quite sure where he’s going with that, though, because I don’t really see how my Quest 3 is any more “open” than my Vision Pro. Are they going to license the OS to other headset makers?

Cue Zuckerberg yesterday:

Some updates on the metaverse today. We are releasing Meta Horizon OS, our operating system that powers Quest virtual and mixed reality headsets, and we are partnering with some of the best hardware companies out there to design new headsets that are optimized for all the different ways that people use this tech.

Now, in every era of computing, there are always open and closed models. Apple’s closed model basically went out. Phones are tightly controlled and you’re kind of locked into what they’ll let you do. But it doesn’t have to be that way. In the PC era, the open model won out. You can do a lot more things, install mods. You got more diversity of hardware, software and more. So our goal is to make it so the open model defines the next generation of computing again with the metaverse, glasses and headsets. That’s why we’re releasing our operating systems so that more companies can build different things on it.

It’s natural to view this announcement as a reaction to the Vision Pro, or perhaps to Google’s upcoming AR announcment at Google I/O, which is rumored to include a new Samsung headset. However, I think that this sells Zuckerberg and Meta’s strategic acumen short: this is an obvious next step, of a piece with the company’s recent AI announcements, and a clear missing piece in the overall metaverse puzzle.

Meta’s Market

Any question of strategy starts with understanding your market, so what is Meta’s? This is a trickier question than you might think, particularly on the Internet. It’s a definition that has particularly vexed regulators, as I laid out in Regulators and Reality; after describing why the FTC’s extremely narrow definition of “personal social networking” — which excluded everything from Twitter to Reddit to LinkedIn to TikTok to YouTube as Facebook competitors — didn’t make sense, I explained:

The far bigger problem, though, is that everything I just wrote is meaningless, because everything listed above is a non-rivalrous digital service with zero marginal costs and zero transactional costs; users can and do use all of them at the same time. Indeed, the fact that all of these services can and do exist for the same users at the same time makes the case that Facebook’s market is in fact phenomenally competitive.

What, though, is Facebook competing for? Competition implies rivalry, that is, some asset that can only be consumed by one service to the exclusion of others, and the only rivalrous good in digital services is consumer time and attention. Users only have one set of eyes, and only 24 hours in a day, and every second spent with one service is a second not spent with another (although this isn’t technically true, since you could, say, listen to one while watching another while scrolling a third while responding to notifications from a fourth, fifth, and sixth). Note the percentages in this chart of platform usage:

The total is not 100, it is 372, because none of these services exclude usage of any of the others. And while Facebook is obviously doing well in terms of total users, TikTok in particular looms quite large when it comes to time, the only metric that matters:

This, of course, is why all of these services, including Instagram, Snapchat, and YouTube are trying to mimic TikTok as quickly as possible, which, last time I checked, is a competitive response, not a monopolistic one. You can even grant the argument that Facebook tried to corner the social media market — whatever that is — a decade ago, but you have to also admit that here in 2021 it is clear that they failed. Competition is the surest sign that there was not actually any anticompetitive conduct, and I don’t think it is the FTC’s job to hold Facebook management accountable for failing to achieve their alleged goals.

This idea that time and attention is the only scarce resource on the Internet, and thus the only market that truly matters, is what undergirds Netflix’s shift in reporting away from members and towards engagement; the company has been saying for years that its competitors were not just other streaming services, but everything from YouTube to Twitch streaming to video games to social media. That has always been true, if you squint, but on the Internet, where everything is only a click (or app) away, it’s tangible.

Meta’s Differentiation

Defining the relevant market as time and attention has surprising implications, that even companies raised on the Internet, including Meta, sometimes miss. Indeed, there was a time when Meta might have agreed with the FTC’s definition, because the company made competitive decisions — both big successes and big mistakes — predicated on the assumption that your personal social network was the market that mattered.

Start with an Article I wrote in 2015 entitled Facebook and the Feed:

Zuckerberg is quite clear about what drives him; he wrote in Facebook’s S-1:

Facebook was not originally created to be a company. It was built to accomplish a social mission – to make the world more open and connected.

I am starting to wonder if these two ideas — company versus mission — might not be more in tension now than they have ever been in the past…I suspect that Zuckerberg for one subscribes to the first idea: that people find what others say inherently valuable, and that it is the access to that information that makes Facebook indispensable. Conveniently, this fits with his mission for the company. For my part, though, I’m not so sure. It’s just as possible that Facebook is compelling for the content it surfaces, regardless of who surfaces it. And, if the latter is the case, then Facebook’s engagement moat is less its network effects than it is that for almost a billion users Facebook is their most essential digital habit: their door to the Internet.

A year later and Facebook responded to what was then its most pressing threat, Snapchat, by putting Stories into Instagram. I wrote in The Audacity of Copying Well:

For all of Snapchat’s explosive growth, Instagram is still more than double the size, with far more penetration across multiple demographics and international users. Rather than launch a “Stories” app without the network that is the most fundamental feature of any app built on sharing, Facebook is leveraging one of their most valuable assets: Instagram’s 500 million users.

The results, at least anecdotally, speak for themselves: I’ve seen more Instagram stories in the last 24 hours than I have Snapchat ones. Of course a big part of this is the novelty aspect, which will fade, and I follow a lot more people on Instagram than I do on Snapchat. That last point, though, is, well, the point: I and my friends are not exactly Snapchat’s target demographic today, but for the service to reach its potential we will be eventually. Unless, of course, Instagram Stories ends up being good enough.

It was good enough — Instagram arrested Snapchat’s growth, while boosting its own engagement and user base — so score one for Zuckerberg, right? Instagram had a better network, so they won…or did they simply have more preexisting usage, which while based on a network, was actually incidental to it?

Fast forward a few years and now Facebook’s big competitor was TikTok; I wrote in 2020’s The TikTok War:

All of this explains what makes TikTok such a breakthrough product. First, humans like video. Second, TikTok’s video creation tools were far more accessible and inspiring for non-professional videographers. The crucial missing piece, though, is that TikTok isn’t really a social network…by expanding the library of available video from those made by your network to any video made by anyone on the service, Douyin/TikTok leverages the sheer scale of user-generated content to generate far more compelling content than professionals could ever generate, and relies on its algorithms to ensure that users are only seeing the cream of the crop.

In a follow-up Update I explained why this was a blindspot for Facebook:

First, Facebook views itself first-and-foremost as a social network, so it is disinclined to see that as a liability. Second, that view was reinforced by the way in which Facebook took on Snapchat. The point of The Audacity of Copying Well is that Facebook leveraged Instagram’s social network to halt Snapchat’s growth, which only reinforced that the network was Facebook’s greatest asset, making the TikTok blindspot even larger.

I am, in the end, actually making the same point as the previous section: Meta’s relevant market is user time and attention; it follows that Meta’s differentiation is the fact it marshals so much user time and attention, and that said marshaling was achieved via social networking is interesting but not necessarily strategically relevant. Indeed, Instagram in the end simply copied TikTok, surfacing content from anywhere on your network, and did so to great success.

Llama 3

This is the appropriate framework to understand Meta’s AI strategy with its Llama family of models: Llama 3 was released last week, and like Llama 2, it is open source, or, perhaps more accurately, open weights (with the caveat that hyperscalers need a license to offer Llama as a managed model). I explained why open weights makes sense in a May 2023 Update predicting the Llama 2 release:

Meta isn’t selling its capabilities; rather, it sells a canvas for users to put whatever content they desire, and to consume the content created by other users. It follows, then, that Meta ought to be fairly agnostic about how and where that content is created; by extension, if Meta were to open source its content creation models, the most obvious place where the content of those models would be published is on Meta platforms. To put it another way, Meta’s entire business is predicated on content being a commodity; making creation into a commodity as well simply provides more grist for the mill.

What is compelling about this reality, and the reason I latched onto Zuckerberg’s comments in that call, is that Meta is uniquely positioned to overcome all of the limitations of open source, from training to verification to RLHF to data quality, precisely because the company’s business model doesn’t depend on having the best models, but simply on the world having a lot of them.

The best analogy for Meta’s approach with Llama is what the company did in the data center. Google had revolutionized data center design in the 2000s, pioneering the use of commodity hardware with software-defined functionality; Facebook didn’t have the scale to duplicate Google’s differentiation in 2011, so it went in the opposite direction and created the Open Compute Project. Zuckerberg explained what happened next in an interview with Dwarkesh Patel:

We don’t tend to open source our product. We don’t take the code for Instagram and make it open source. We take a lot of the low-level infrastructure and we make that open source. Probably the biggest one in our history was our Open Compute Project where we took the designs for all of our servers, network switches, and data centers, and made it open source and it ended up being super helpful. Although a lot of people can design servers the industry now standardized on our design, which meant that the supply chains basically all got built out around our design. So volumes went up, it got cheaper for everyone, and it saved us billions of dollars which was awesome.

Zuckerberg then made the analogy I’m referring to:

So there’s multiple ways where open source could be helpful for us. One is if people figure out how to run the models more cheaply. We’re going to be spending tens, or a hundred billion dollars or more over time on all this stuff. So if we can do that 10% more efficiently, we’re saving billions or tens of billions of dollars. That’s probably worth a lot by itself. Especially if there are other competitive models out there, it’s not like our thing is giving away some kind of crazy advantage.

It’s not just about having a better model, though: it’s about ensuring that Meta doesn’t have a dependency on any one model as well. Zuckerberg continued:

Here’s one analogy on this. One thing that I think generally sucks about the mobile ecosystem is that you have these two gatekeeper companies, Apple and Google, that can tell you what you’re allowed to build. There’s the economic version of that which is like when we build something and they just take a bunch of your money. But then there’s the qualitative version, which is actually what upsets me more. There’s a bunch of times when we’ve launched or wanted to launch features and Apple’s just like “nope, you’re not launching that.” That sucks, right? So the question is, are we set up for a world like that with AI? You’re going to get a handful of companies that run these closed models that are going to be in control of the APIs and therefore able to tell you what you can build?

For us I can say it is worth it to go build a model ourselves to make sure that we’re not in that position. I don’t want any of those other companies telling us what we can build. From an open source perspective, I think a lot of developers don’t want those companies telling them what they can build either. So the question is, what is the ecosystem that gets built out around that? What are interesting new things? How much does that improve our products? I think there are lots of cases where if this ends up being like our databases or caching systems or architecture, we’ll get valuable contributions from the community that will make our stuff better. Our app specific work that we do will then still be so differentiated that it won’t really matter. We’ll be able to do what we do. We’ll benefit and all the systems, ours and the communities’, will be better because it’s open source.

There is another analogy here, which is Google and Android; Bill Gurley wrote the definitive Android post in 2011 on his blog Above the Crowd:

Android, as well as Chrome and Chrome OS for that matter, are not “products” in the classic business sense. They have no plan to become their own “economic castles.” Rather they are very expensive and very aggressive “moats,” funded by the height and magnitude of Google’s castle. Google’s aim is defensive not offensive. They are not trying to make a profit on Android or Chrome. They want to take any layer that lives between themselves and the consumer and make it free (or even less than free). Because these layers are basically software products with no variable costs, this is a very viable defensive strategy. In essence, they are not just building a moat; Google is also scorching the earth for 250 miles around the outside of the castle to ensure no one can approach it. And best I can tell, they are doing a damn good job of it.

The positive economic impact of Android (and Chrome) is massive: the company pays Apple around $20 billion a year for default placement on about 30% of worldwide smartphones (and Safari on Apple’s other platforms), which accounts for about 40% of the company’s overall spend on traffic acquisition costs across every other platform and browser. That total would almost certainly be much higher — if Google were even allowed to make a deal, which might not be the case if Microsoft controlled the rest of the market — absent Android and Chrome.

Metaverse Motivations

Android is also a natural segue to this news about Horizon OS. Meta is, like Google before it, a horizontal services company funded by advertising, which means it is incentivized to serve everyone, and to have no one between itself and its customers. And so Meta is, like Google before it, spending a huge amount of money to build a contender for what Zuckerberg believes is a future platform. It’s also fair to note that Meta is spending a lot more than the $40 billion Google has put into Android, but I think it’s reasonable: the risk — and opportunity — for Meta in the metaverse is even higher than the risk Google perceived in smartphones.

Back in 2013, when Facebook was facing the reality that mobile was ending its dreams of being a platform in its own right, I wrote Mobile Makes Facebook Just an App; That’s Great News:

First off, mobile apps own the entire (small) screen. You see nothing but the app that you are using at any one particular time. Secondly, mobile apps are just that: apps, not platforms. There is no need for Facebook to “reserve space” in their mobile apps for partners or other apps. That’s why my quote above is actually the bull case for Facebook.

Specifically, it’s better for an advertising business to not be a platform. There are certain roles and responsibilities a platform must bear with regards to the user experience, and many of these work against effective advertising. That’s why, for example, you don’t see any advertising in Android, despite the fact it’s built by the top advertising company in the world. A Facebook app owns the entire screen, and can use all of that screen for what benefits Facebook, and Facebook alone.

This optimism was certainly borne out by Facebook’s astronomical growth over the last decade, which has been almost entirely about exploiting this mobile advertising opportunity. It also, at first glance, calls into question the wisdom of building Horizon OS, given the platform advertising challenges I just detailed.

The reality, though, is that a headset is fundamentally different than a smartphone: the latter is something you hold in a hand, and which an app can monopolize; the former monopolizes your vision, reducing an app to a window. Consider this PR image of the Vision Pro:

This isn’t the only canvas for apps in the Vision Pro: apps can also take over the entire view and provide an immersive experience, and I can imagine that Meta will, when and if the Vision Pro gains meaningful marketshare, build just that; remember, Meta is a horizontal services company, and that means serving everyone. Ultimately, though, Zuckerberg sees the chief allure of the metaverse as being about presence, which means the sensation of feeling like you are in the same place as other people enjoying the same experiences and apps; that, by extension, means owning the layer within which apps live — it means owning your entire vision.

Just as importantly — probably most importantly, to Zuckerberg — owning the OS means not being subject to Apple’s dictate on what can or cannot be built, or tracked, or monetized. And, as Zuckerberg noted in that interview, Meta isn’t particularly keen to subject itself to Google, either. It might be tempting for Meta’s investors to dismiss these concerns, but ATT should have focused minds about just how much this lack of control can cost.

Finally, not all devices will be platforms: Meta’s RayBan sunglasses, for example, could not be “just an app”; what they could be is that much better of a product if Apple made public the same sort of private APIs it makes available to its own accessories. Meta isn’t going to fix its smartphone challenges in that regard, but it is more motivation to do their own thing.

Horizon OS

Motivations, of course, aren’t enough: unlike AI models, where Meta wants a competitive model, but will achieve its strategic goals as long as a closed model doesn’t win, the company does actually need to win in the metaverse by controlling the most devices (assuming, of course, that the metaverse actually becomes a thing).

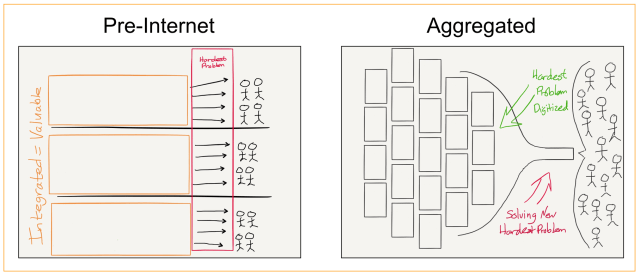

The first thing to note is that pursuing an Apple-like fully-integrated model would actually be bad for Meta’s larger goals, which, as a horizontal services company, is reaching the maximum number of people possible; there is a reason that the iPhone, by far the most dominant integrated product ever, still only has about 30% marketshare worldwide. Indeed, I would pushback on Zuckerberg’s continued insistence that Apple “won” mobile: they certainly did as far as revenue and profits go, but the nature of their winning is not the sort of winning that Meta should aspire to; from a horizontal services company perspective, Android “won” because it has the most marketshare.

Second, the best route to achieving that marketshare is exactly what Meta announced: licensing their operating system to device manufacturers who are not only motivated to sell devices, but also provide the necessary R&D and disparate channels to develop headsets for a far wider array of customers and use cases.

Third, Meta does have the opportunity to actually accomplish what pundits were sure would befall the iPhone: monopolize developer time and attention. A big reason why pundits were wrong about the iPhone, back when they were sure that it was doomed to disruption, was that they misunderstood history. I wrote in 2013’s The Truth About Windows Versus the Mac:

You’ve heard the phrase, “No one ever got fired for buying IBM.” That axiom in fact predates Microsoft or Apple, having originated during IBM’s System/360 heyday. But it had a powerful effect on the PC market. In the late 1970s and very early 1980s, a new breed of personal computers were appearing on the scene, including the Commodore, MITS Altair, Apple II, and more. Some employees were bringing them into the workplace, which major corporations found unacceptable, so IT departments asked IBM for something similar. After all, “No one ever got fired…”

IBM spun up a separate team in Florida to put together something they could sell IT departments. Pressed for time, the Florida team put together a minicomputer using mostly off-the shelf components; IBM’s RISC processors and the OS they had under development were technically superior, but Intel had a CISC processor for sale immediately, and a new company called Microsoft said their OS — DOS — could be ready in six months. For the sake of expediency, IBM decided to go with Intel and Microsoft.

The rest, as they say, is history. The demand from corporations for IBM PCs was overwhelming, and DOS — and applications written for it — became entrenched. By the time the Mac appeared in 1984, the die had long since been cast. Ultimately, it would take Microsoft a decade to approach the Mac’s ease-of-use, but Windows’ DOS underpinnings and associated application library meant the Microsoft position was secure regardless.

Evans is correct: the market today for mobile phones is completely different than the old market for PCs. And, so is Apple’s starting position; iOS was the first modern smartphone platform, and has always had the app advantage. Neither was the case in PCs. The Mac didn’t lose to Windows; it failed to challenge an already-entrenched DOS. The lessons that can be drawn are minimal.

The headset market is the opposite of the smartphone market: Meta has been at this for a while, and has a much larger developer base than Apple does, particularly in terms of games. It’s not overwhelming like Microsoft’s DOS advantage already was, to be sure, and I’m certainly not counting out Apple, but this also isn’t the smartphone era where Apple had a multi-year head start.

To that end, it’s notable that Meta isn’t just licensing Horizon OS, it is also opening up the allowable app model. From the Oculus Developer blog:

We’re also significantly changing the way we manage the Meta Horizon Store. We’re shifting our model from two independent surfaces, Store and App Lab, to a single, unified, open storefront. This shift will happen in stages, first by making many App Lab titles available in a dedicated section of the Store, which will expand the opportunity for those titles to reach their audiences. In the future, new titles submitted will go directly to the Store, and App Lab will no longer be a separate distribution channel. All titles will still need to meet basic technical, content, and privacy requirements to publish to the Store. Titles are reviewed at submission and may be re-reviewed as they scale to more people. Like App Lab today, all titles that meet these requirements will be published.

App Lab apps are a middle ground between side-loading (which Horizon OS supports) and normal app store distribution: developers get the benefit of an App Store (easy install, upgrades, etc.) without having to go through full App Review; clear a basic bar and your app will be published. This allows for more experimentation.

What it does not allow for is new business models: App Lab apps, if they monetize, still must use Horizon OS’s in-app payment system. To that end, I think that Meta should consider going even further, and offering up a truly open store: granted, this will reduce the long-run monetization potential of Horizon OS, but it seems to me like that would be an excellent problem to have, given it would mean there was a long-run to monetize in the first place.

The Meaning of Open

This remaining limitation does get at the rather fuzzy meaning of “open”: in the case of Horizon OS, Meta means a licensing model for its OS and more freedom for developers relative to Apple; in the case of Llama Meta means open weights and making models into a commodity; in the case of data centers Meta means open specifications, and in the case of projects like React or PyTorch Meta means true open source code.

Meta, in other words, is not taking some sort of philosophical stand: rather, they are clear-eyed about what their market is (time and attention), and their core differentiation (horizontal services that capture more time and attention than anyone); everything that matters in pursuit of that market and maintenance of that differentiation is worth investing in, and if “openness” means that investment goes further or performs better or handicaps a competitor, then Meta will be open.