Last week the German Bundeskartellamt (“Federal Cartel Office”) announced in a press release:

The Bundeskartellamt has initiated a proceeding against the technology company Apple to review under competition law its tracking rules and the App Tracking Transparency Framework. In particular, Apple’s rules have raised the initial suspicion of self-preferencing and/or impediment of other companies, which will be examined in the proceeding.

The press release quoted Andreas Mundt, the President of the Bundeskartellamt, who stated:

We welcome business models which use data carefully and give users choice as to how their data are used. A corporation like Apple which is in a position to unilaterally set rules for its ecosystem, in particular for its app store, should make pro-competitive rules. We have reason to doubt that this is the case when we see that Apple’s rules apply to third parties, but not to Apple itself. This would allow Apple to give preference to its own offers or impede other companies.

The press release continues:

Already based on the applicable legislation, and irrespective of Apple’s App Tracking Transparency Framework, all apps have to ask for their users’ consent to track their data. Apple’s rules now also make tracking conditional on the users’ consent to the use and combination of their data in a dialogue popping up when an app not made by Apple is started for the first time, in addition to the already existing dialogue requesting such consent from users. The Identifier for Advertisers, classified as tracking, which is important to the advertising industry and made available by Apple to identify devices, is also subject to this new rule. These rules apparently do not affect Apple when using and combining user data from its own ecosystem. While users can also restrict Apple from using their data for personalised advertising, the Bundeskartellamt’s preliminary findings indicate that Apple is not subject to the new and additional rules of the App Tracking Transparency Framework.

John Gruber disagrees at Daring Fireball:

I think this is a profound misunderstanding of what Apple is doing, and how Apple is benefiting indirectly from ATT. Apple’s privacy and tracking rules do apply to itself. Apple’s own apps don’t show the track-you-across-other-apps permission alert not because Apple has exempted itself but because Apple’s own apps don’t track you across other apps. Apple’s own apps show privacy report cards in the App Store, too…

If you want to argue that Apple engaged in this entire ATT endeavor to benefit its own Search Ads platform, that’s plausible too. But if Apple actually cared more about maximizing Search Ads revenue than it does user privacy, wouldn’t they have just engaged in actual user tracking? The Bundeskartellamt perspective here completely disregards the idea that surveillance advertising is inherently unethical and Apple has studiously avoided it for that reason, despite the fact that it has proven to be wildly profitable for large platforms.

This strikes me as a situation where Gruber — my co-host for Dithering — is right on the details, even as the Bundeskartellamt is right on the overall thrust of the argument. The distinction comes down to definitions.

It’s striking in retrospect how little time Apple spent publicly discussing its App Tracking Transparency (ATT) initiative — a mere 20 seconds at WWDC 2020, wedged in between updates about camera-in-use indicators and privacy labels in the App Store:

Next, let’s talk about tracking. Safari’s Intelligent Tracking Prevention has been really successful on the web, and this year, we wanted to help you with tracking in apps. We believe tracking should always be transparent, and under your control, so moving forward, App Store policy will require apps to ask before tracking you across apps and websites owned by other companies.

These 20 seconds led, 19 months later, to Meta announcing a $10 billion revenue shortfall, the largest but by no means only significant retrenchment in the online advertising space. Not everyone was hurt, though: Google and Amazon, in particular, have seen their share of digital advertising increase, and, as Gruber admitted, Apple has benefited as well; the Financial Times reported last fall:

Apple’s advertising business has more than tripled its market share in the six months after it introduced privacy changes to iPhones that obstructed rivals, including Facebook, from targeting ads at consumers. The in-house business, called Search Ads, offers sponsored slots in the App Store that appear above search results. Users who search for “Snapchat”, for example, might see TikTok as the first result on their screen. Branch, which measures the effectiveness of mobile marketing, said Apple’s in-house business is now responsible for 58 per cent of all iPhone app downloads that result from clicking on an advert. A year ago, its share was 17 per cent.

These numbers, derived as they are from app analytics companies, are certainly fuzzy, but they are the best we have given that Apple doesn’t break out revenue numbers for its advertising business; they are also from last fall, before ATT really began to bite. They also exclude the revenue Apple earns from Google for being the default search engine for Safari, and while Google’s earnings indicate YouTube has suffered from ATT, search has more than made up for it.

I explained in depth why these big companies have benefitted from ATT in February’s Digital Advertising in 2022; I wrote in the context of Amazon specifically:

Amazon also has data on its users, and it is free to collect as much of it as it likes, and leverage it however it wishes when it comes to selling ads. This is because all of Amazon’s data collection, ad targeting, and conversion happen on the same platform — Amazon.com, or the Amazon app. ATT only restricts third party data sharing, which means it doesn’t affect Amazon at all…

That is not to say that ATT didn’t have an effect on Amazon: I noted above that Snap’s business did better than expected in part because its business wasn’t dominated by direct response advertising to the extent that Facebook’s was, and that more advertising money flowed into other types of advertising. This almost certainly made a difference for Amazon as well: one of the most affected areas of Facebook advertising was e-commerce; if you are an e-commerce seller whose Shopify store powered-by Facebook ads was suddenly under-performing thanks to ATT, then the natural response is to shift products and advertising spend to Amazon.

This is where definitions matter. The opening paragraph of Apple’s Advertising & Policy page, housed under the “apple.com/legal” directory, states:

Ads that are delivered by Apple’s advertising platform may appear on the App Store, Apple News, and Stocks. Apple’s advertising platform does not track you, meaning that it does not link user or device data collected from our apps with user or device data collected from third parties for targeted advertising or advertising measurement purposes, and does not share user or device data with data brokers.

I note the URL path for a reason: the second sentence of this paragraph has multiple carefully selected words — and those word choices not only impact the first sentence, but may, soon enough, lead to its expansion. Specifically:

“Meaning”

Apple’s advertising platform does not track you,

“Tracking” is not a neutral term! My strong suspicion — confirmed by anecdata — is that a lot of the most ardent defenders of Apple’s ATT policy are against targeted advertising as a category, which is to say they are against companies collecting data and using that data to target ads. For these folks I would imagine tracking means exactly that: the collection and use of data to target ads. That certainly seems to align with the definition of “track” from macOS’s built-in dictionary: “Follow the course or trail of (someone or something), typically in order to find them or note their location at various points”.

However, this is not Apple’s definition: tracking is only when data Apple collects is linked with data from third parties for targeted advertising or measurement, or when data is shared/sold to data brokers. In other words, data that Apple collects and uses for advertising is, according to Apple, not tracking; the privacy policy helpfully lays out exactly what that data is (thanks lawyers!):

We create segments, which are groups of people who share similar characteristics, and use these groups for delivering targeted ads. Information about you may be used to determine which segments you’re assigned to, and thus, which ads you receive. To protect your privacy, targeted ads are delivered only if more than 5,000 people meet the targeting criteria.

We may use information such as the following to assign you to segments:

- Account Information: Your name, address, age, gender, and devices registered to your Apple ID account. Information such as your first name in your Apple ID registration page or salutation in your Apple ID account may be used to derive your gender. You can update your account information on the Apple ID website.

Downloads, Purchases & Subscriptions: The music, movies, books, TV shows, and apps you download, as well as any in-app purchases and subscriptions. We don’t allow targeting based on downloads of a specific app or purchases within a specific app (including subscriptions) from the App Store, unless the targeting is done by that app’s developer.

Apple News and Stocks: The topics and categories of the stories you read and the publications you follow, subscribe to, or turn on notifications from.

Advertising: Your interactions with ads delivered by Apple’s advertising platform.

When selecting which ad to display from multiple ads for which you are eligible, we may use some of the above-mentioned information, as well as your App Store searches and browsing activity, to determine which ad is likely to be most relevant to you. App Store browsing activity includes the content and apps you tap and view while browsing the App Store. This information is aggregated across users so that it does not identify you. We may also use local, on-device processing to select which ad to display, using information stored on your device, such as the apps you frequently open.

Just to put a fine point on this: according to Apple’s definition, collecting demographic information, downloads/purchases/subscriptions, and browsing behavior in Apple’s apps, and using that data to deliver targeted ads, is not tracking, because all of the data is Apple’s (and by extension, neither is Google’s collection and use of data from Safari search results, or Amazon’s collection and use of data from its app; however, a developer associating an in-app purchase with a Facebook ad is).

“And”

Apple’s advertising platform does not track you, meaning that it does not link user or device data collected from our apps with user or device data collected from third parties for targeted advertising or advertising measurement purposes,

One thing should be made clear: there has been a lot of bad behavior in the digital ad industry. A particularly vivid example was reported by the Wall Street Journal last month:

The precise movements of millions of users of the gay-dating app Grindr were collected from a digital advertising network and made available for sale, according to people familiar with the matter. The information was available for sale since at least 2017, and historical data may still be obtainable, the people said. Grindr two years ago cut off the flow of location data to any ad networks, ending the possibility of such data collection today, the company said.

The commercial availability of the personal information, which hasn’t been previously reported, illustrates the thriving market for at-times intimate details about users that can be harvested from mobile devices. A U.S. Catholic official last year was outed as a Grindr user in a high-profile incident that involved analysis of similar data. National-security officials have also indicated concern about the issue: The Grindr data were used as part of a demonstration for various U.S. government agencies about the intelligence risks from commercially available information, according to a person who was involved in the presentation.

Clients of a mobile-advertising company have for years been able to purchase bulk phone-movement data that included many Grindr users, said people familiar with the matter. The data didn’t contain personal information such as names or phone numbers. But the Grindr data were in some cases detailed enough to infer things like romantic encounters between specific users based on their device’s proximity to one another, as well as identify clues to people’s identities such as their workplaces and home addresses based on their patterns, habits and routines, people familiar with the data said.

It’s difficult to defend any aspect of this, and this isn’t even a worst case scenario: there are plenty of unscrupulous apps and ad networks that include explicit Personal Identifiable Information (PII) in these data sales/transfers as well; as Eric Suefert noted in 2020, the industry has had this reckoning coming for a very long time.

That, though, is why the “and” from Apple is so meaningful; here is the sentence again:

Apple’s advertising platform does not track you, meaning that it does not link user or device data collected from our apps with user or device data collected from third parties for targeted advertising or advertising measurement purposes, and does not share user or device data with data brokers.

This definition conflates two very different things: linking and sharing. The distinction between the two undergirded a regular feature of Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s appearances in Congressional hearings; here is a representative exchange between Senator Edward Markey and Zuckerberg in 2018:

Should Facebook get clear permission from users before selling or sharing sensitive information about your health, your finances, your relationships? Should you have to get their permission?…

Senator…I want to be clear: we don’t sell information. So regardless of whether we get permission to do that, that’s just not a thing we’re going to do.

Meta doesn’t sell data; it collects it, and the third parties that leverage the company’s platforms for advertising very much prefer it that way. PII is like radioactive material: it’s very valuable, and can certainly be leveraged, but it’s also difficult to handle and can be dangerous to not just the users identified but to the companies holding it. The way Meta works is that its collective advertising base has effectively deputized the company to collect data on their behalf; that data is not exposed directly, but is instead used to deliver targeted advertisements that are by-and-large bought not by targeting specific criteria, but rather by specifying desired results: app installs, e-commerce conversions, etc. Everything user-related is, to the companies buying the ads, a complete black box.

This is where linking comes in: apps or websites that leverage Facebook advertising (or any other relevant advertising platform, like Snap) include a Facebook SDK or Pixel that tracks installs, sales, etc., and sends that data to Meta where it can be linked to an ad that was shown to that user. Again, this is completely invisible to the developer or merchant; technically they are sending data to Meta, since the conversion data was collected in their app or on their website, but in reality it is Meta collecting that data and sending it to themselves.

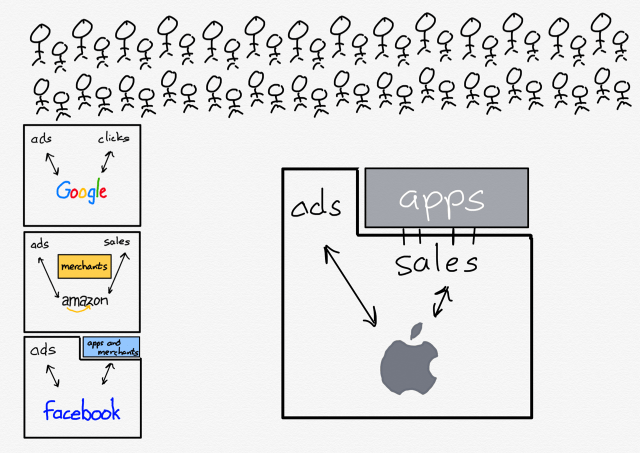

The reason why developers and merchants are happy with this arrangement is that advertising is a scale business: you need a lot of data and a lot of customers to make targeted advertising work, and no single developer or website has as much scale as, say, a Google or an Amazon; Meta et al enable all of these smaller developers and merchants to effectively work together without having to know each other, or share data.

You can, to be clear, object to this arrangement, but it’s worth pointing out that this is very different than selling or sharing data with data brokers; all of the data is in one place and one place only, which is broadly similar to the situation with Google or Amazon (or Apple, as I’ll get to in a moment). The big difference is that Meta doesn’t own all of the customer touch points: whereas a Meta advertiser may own their own Shopify website, an Amazon advertiser has to list their goods on Amazon’s site, with all of the loss of control that entails. Apple’s definition, though, lumps Meta’s approach (which again, is representative of other platforms like Snap) in with the worst actors in the space.

“Our”

Apple’s advertising platform does not track you, meaning that it does not link user or device data collected from

To the extent you think that the Bundeskartellamt is right, then it is this word that is the most problematic definition of all. One would assume that “our” means Apple-created apps, like News or Stocks: just as Amazon collects data from the Amazon app, of course Apple collects data from its own apps. The actual definition, though, is much more expansive; go back to the Epic trial and the exchange I recounted in App Store Arguments:

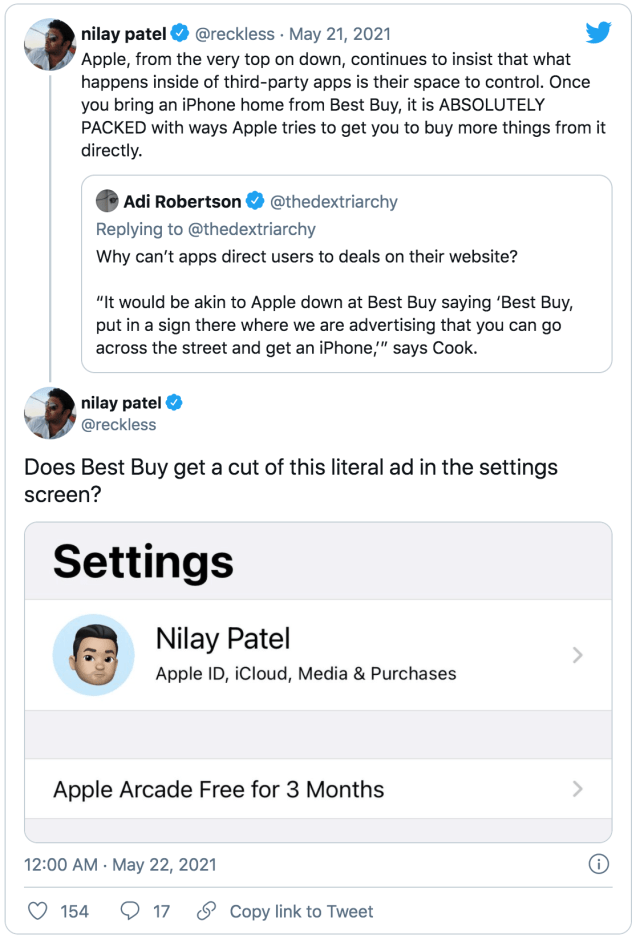

The argument that Judge Gonzales Rogers seemed the most interested in pursuing was one that Epic de-emphasized: Apple’s anti-steering provisions which prevent an app from telling a customer that they can go elsewhere to make a purchase. Apple’s argument, in this case presented by Cook, goes like this:

This analogy doesn’t work for all kinds of reasons; Apple’s ban is like Best Buy not allowing products in the store to have a website listed in the instruction manual that happens to sell the same products. In fact, as Nilay Patel noted, Apple does exactly this!

The point of this Article, though, is not necessarily to refute arguments, but rather to highlight them, and for me this was the most illuminating part of this case. The only way that this analogy makes sense is if Apple believes that it owns every app on the iPhone, or, to be more precise, that the iPhone is the store, and apps in the store can never leave.

Let me be precise in a different way that is relevant to this Article; Apple doesn’t particularly care about or claim ownership of the content of an app on the iPhone, but:

- Apple insists that every app on the iPhone use its payment system for digital content

- Apple treats all transactions made through its payment system as Apple data

- Ergo, all transactions for digital content on the iPhone are Apple data

The end result looks something like this — i.e. strikingly similar to Facebook, but with App Store payments attached:

Here’s the key point: when it comes to digital advertising, particularly for the games that make up the vast majority of the app advertising industry, transaction data is all that matters. All of the data that any platform collects, whether that be Meta, Snap, Google, etc. is insignificant compared to whether or not a specific ad led to a specific purchase, not just in direct response to said ad, but also over the lifetime of the consumer’s usage of said app. That is the data that Apple cut off with ATT (by barring developers from linking it to their ad spend), and it is the same data that Apple has declared is their own first party data, and thus not subject to its ban on “tracking.”

This, needless to say, is where legitimate questions about self-preferencing come to the forefront. Developers who want to link conversion data with Facebook are banned from doing so, while they have no choice but to share that data with Apple because Apple controls app installation via the App Store; this strikes me as a clear example of the President of the Bundeskartellamt’s claim that “Apple’s rules apply to third parties, but not to Apple itself”.

I have been very clear that I disagree with those who want to ban all targeted advertising; I believe that targeted advertising is an essential ingredient in a new Internet economy that provides opportunities to small businesses serving niches that are only viable when the world is your market. After all, people who might love your product need some way to know that your product exists, and what is compelling about platforms like Facebook is that it completely leveled the advertising playing field: suddenly small businesses had the same tools and opportunities to advertise as the biggest companies in the world. At the same time, I understand and acknowledge those who disagree with the concept on principle.

What is frustrating about the debate about ATT, though, is that Apple presents itself as a representative of the latter, with its constant declarations that privacy is a human right, and advertisements that lean heavily into the (truly problematic) world of data brokering, even as it builds its own targeting advertising business. Gruber asked me on this morning’s episode of Dithering whether or not I would feel better about ATT if Apple weren’t itself doing targeted advertising, and the answer is yes: I would still be disappointed about the impact on the Internet economy, but at least it wouldn’t be so blatantly anti-competitive.

Apple, to its credit, has made moves that very much align with its privacy rhetoric by cleaning up some of the worst abuses by apps, including significantly fine-tuning location permissions, providing a new weather framework that makes it significantly cheaper to build a weather app (reducing the incentive to monetize by selling location data), and increasing transparency around data collection. Moreover, at this year’s WWDC the company introduced significant enhancements to SKAdNetwork that should make it easier for developers and platforms like Facebook to re-build their advertising capabilities.

At the same time, an increasing number of signals suggest that Apple is set to significantly expand their own advertising business; an obvious product to build would be an ad network that runs in apps (given that these apps run on the iPhone, Apple would in this scenario claim that collecting data about who saw what ad would be first party data, just like transactions are). Yes, Apple tried and failed to build an ad network previously, but a big reason that effort failed is because Apple didn’t collect the sort of data necessary to make it succeed.

What has changed is not just Apple, but also the data that matters: when iAd launched in 2010, digital advertising ran like people still think it does, leveraging relatively broad demographic categories and contextual information to show a hopefully relevant ad;1 what matters today is linking an ad to a transaction, and Apple has positioned itself to have perfect knowledge of both, even as it denies others the same opportunity.

This is the era when Facebook earned its reputation for being far too cavalier with user data; Facebook was also the company that built the modern advertising approach that depends on linking data instead of sharing it. ↩

![A human basking in the sun of AGI utopia]](https://i0.wp.com/stratechery.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/dall-e-2.png?resize=640%2C640&ssl=1)