Postulate: The greatest differentiator for iOS is the quality of its apps.

That’s the position taken by Benedict Evans in a must-read piece:

If total Android engagement moves decisively above iOS, the fact that iOS will remain big will be beside the point – it will move from first to first-equal and then perhaps second place on the roadmap. And given the sales trajectories, that could start to happen in 2014. If you have 5-6x the users and a quarter of the engagement, you’re still a more attractive market.

This is a major strategic threat for Apple. A key selling point for the iPhone (though not the only one) is that the best apps are on iPhone and are on iPhone first. If that does change then the virtuous circle of ‘best apps therefore best users therefore best apps’ will start to unwind and the wide array of Android devices at every price point will be much more likely to erode the iPhone base. Part of the reason for spending $600 on an iPhone instead of $300 on an Android is the apps – that cannot be allowed to change.

Still, Evans is careful to note that apps are “not the only [selling point]” for the iPhone. As well he should: there remains an elegance and refinement to iOS relative to the competition that a certain breed of user will simply not give up, even if Android had unique apps.

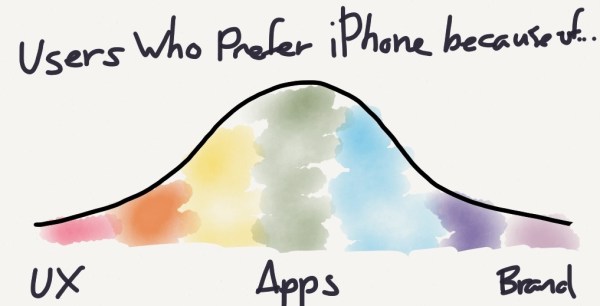

Still, that user is only a portion of iPhone buyers. I don’t have any hard numbers to support this (nor do I have them for any of the assertions in this post; however, I used to analyze the actual numbers behind a lot of this for a living), but I suspect the iPhone-buying population preference distribution looks like something like this:

To the left are the folks I just referenced, who care above all else about the user experience. They would buy an iPhone even if Android had an app they desired.

In the middle are people who buy an iPhone for the apps, and on the right, for branding. Again, this is just the top-level preference; a user may prefer the iPhone’s UX, app selection, and branding, but by definition something is the most important.

Rene Ritchie wrote a great response to Evans’ piece about The Difference Between iOS and Android Developers:

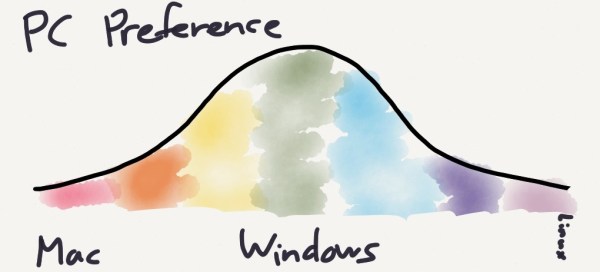

The Mac, though its market share was never large, especially when compared to the well over 90% marketshare of Microsoft Windows-based PCs, had always attracted an incredibly talented, incredibly dedicated group of developers who cared deeply about things like design and user experience. OS X enjoyed not only the traditional Mac OS community, but the NeXT one as well. That talent share always felt disproportionate to the market share. Massively. And a lot of those developers, and new developers influenced by them, not only wanted iPhones and iPads, but wanted to create software for them…

People – developers – aren’t just numbers. They have tastes. They have biases. If they didn’t, then all the great iPhone apps of 2008 would have already been written for Symbian, PalmOS, BlackBerry (J2ME), and Windows Mobile years earlier. If they didn’t, then all the great Mac apps would have been migrated to Windows a decade ago.

It’s interesting to consider the Mac in this context, particularly when it comes to developers. There’s no question Mac market share fit nicely into one tail of a bell curve:

Marco Arment, while not in direct response to Ritchie, made a similar argument about developers building software for platforms they themselves use:

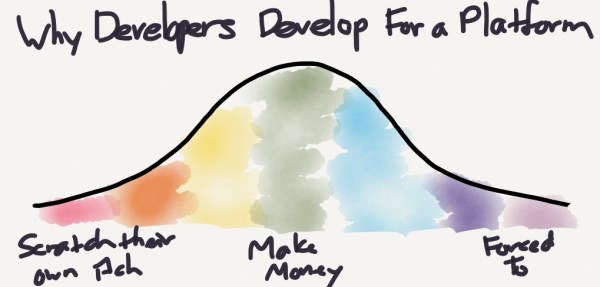

Developers aren’t fools. We aren’t swayed by charismatic figureheads who try to convince us to develop for their platforms. The formula is quite simple. We’ll develop for a platform if:

- We use it.

A lot of other people use it.

We can make a living developing for it.

If your platform nails all three, we’ll develop for it. Nobody will even need to ask us. We’ll break the door down.

Mapping developer motivation to the same bell curve, I’d imagine it looks something like this:

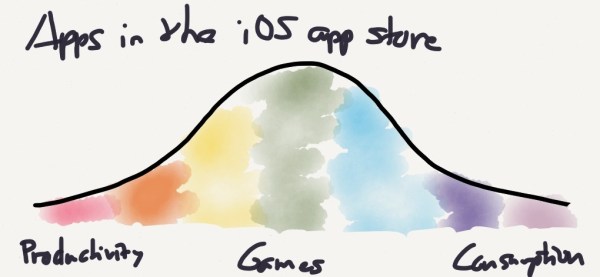

It’s interesting, also, to consider the types of apps that are in the app store. I think there are three broad categories:

- Consumption apps, including both entertainment and social networking These types of apps are front-ends for web services. These services entail massive capital investment, so there is strong motivation to have front-ends on every possible OS in order to maximize the number of users

- Games Games are immersive and thus relatively portable from a UI perspective, but there is a much more significant incremental cost to supporting multiple platforms relative to service-type apps

- Productivity Apps As I wrote previously, “If games are all about user input, with minimal app output, and consumption apps about app output, with minimal user input, productivity apps are about both. You put something into an app, and the app returns something back to you, better.”

Productivity apps are the most attuned to the underlying platform, particularly from a UI perspective, and thus have the highest incremental cost to supporting multiple platforms.

In terms of numbers of apps, the app store looks something like this:

By this point, you’re probably getting sick of the rainbow bell curve, so I’ll consolidate app quality, monetization models, and price:

In fact, and this is the crucial point, I could have consolidated all of the bell curves, because I believe they are highly correlative.

- People who most highly value UX probably also use a Mac. They are more likely to buy (or develop) productivity type apps, prefer paid downloads, and gladly pay higher prices

- On the flip side, the sort of folks that buy an iPhone just because it is cool are probably a lot less likely to see their phone as a productivity tool, or to download much beyond the essential entertainment and social networking apps they derive status from

Ultimately, though, neither tail is particularly interesting; it’s the massive middle that moves markets. While I had similar thoughts to Ritchie about the relative quality and associated motivation of a certain breed of iOS developers, most people aren’t buying iOS devices because of OmniFocus.

Rather, it’s apps like SuperCell’s Clash of Clans, the third-most grossing app in the App Store, or Instagram in the months before the Android version launched, that differentiate the iPhone. Apps like that fall solidly on the middle-to-right side of these bell curves: their developers are much more concerned with making money or maximizing their back-end investment than they are in scratching their own itch, and they will do the exact calculations Evans has suggested.

The average Android smartphone user is worth much less than the average iPhone user, but there are lots more of them.

Let’s be super clear: both Evans and myself are quite dismissive of the idea that iOS:Android::Mac:Windows. But one lesson that can be drawn is that for many developers, money is motivation enough, and for just as many users, app availability – especially games – trumps the user experience.

Evans is right: the lower-cost iPhone can’t arrive soon enough.

One final thing worth noting is geography. In the Valley, the iPhone reigns supreme. It’s genuinely surprising when folks don’t have an iPhone (although not as surprising as when they don’t have a Mac). In Asia, though, Android is far more popular, and it’s Asia where there is, by far, the most growth to be had for smartphone manufacturers. If Android-first development becomes a reality, it will happen here first.