Last week Brian Krzanich resigned as the CEO of Intel after violating the company’s non-fraternization policy. The details of Krzanich’s departure, though, ultimately don’t matter: his tenure was an abject failure, the extent of which is only now coming into view.

Intel’s Obsolete Opportunity

When Krzanich was appointed CEO in 2013 it was already clear that arguably the most important company in Silicon Valley’s history was in trouble: PCs, long Intel’s chief money-maker, were in decline, leaving the company ever more reliant on the sale of high-end chips to data centers; Intel had effectively zero presence in mobile, the industry’s other major growth area.

Still, I framed the situation that faced Krzanich as an opportunity, and drew a comparison to the challenges that faced the legendary Andy Grove three decades ago:

By the 1980s, though, it was the microprocessor business, fueled by the IBM PC, that was driving growth, while the DRAM business was fully commoditized and dominated by Japanese manufacturers. Yet Intel still fashioned itself a memory company. That was their identity, come hell or high water.

By 1986, said high water was rapidly threatening to drag Intel under. In fact, 1986 remains the only year in Intel’s history that they made a loss. Global overcapacity had caused DRAM prices to plummet, and Intel, rapidly becoming one of the smallest players in DRAM, felt the pain severely. It was in this climate of doom and gloom that Grove took over as CEO. And, in a highly emotional yet patently obvious decision, he once and for all got Intel out of the memory manufacturing business.

Intel was already the best microprocessor design company in the world. They just needed to accept and embrace their destiny.

Fast forward to the challenge that faced Krzanich:

It is into a climate of doom and gloom that Krzanich is taking over as CEO. And, in what will be a highly emotional yet increasingly obvious decision, he ought to commit Intel to the chip manufacturing business, i.e. manufacturing chips according to other companies’ designs.

Intel is already the best microprocessor manufacturing company in the world. They need to accept and embrace their destiny.

That article is now out of date: in a remarkable turn of events, Intel has lost its manufacturing lead. Ben Bajarin wrote last week in Intel’s Moment of Truth:

Not only has the competition caught Intel they have surpassed them. TSMC is now sampling on 7nm and AMD will ship their architecture on 7nm technology in both servers and client PCs ahead of Intel. For those who know their history, this is the first time AMD has ever beat Intel to a process node. Not only that, but AMD will likely have at least an 18 month lead on Intel with 7nm, and I view that as conservative.

As Bajarin notes, 7nm for TSMC (or Samsung or Global Foundries) isn’t necessarily better than Intel’s 10nm; chip-labeling isn’t what it used to be. The problem is that Intel’s 10nm process isn’t close to shipping at volume, and the competition’s 7nm processes are. Intel is behind, and its insistence on integration bears a large part of the blame.

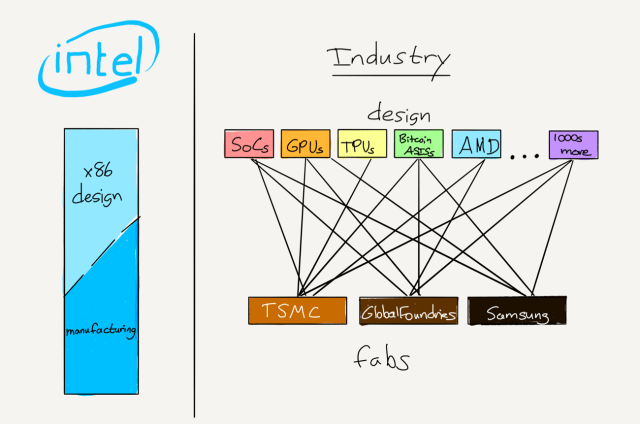

Intel’s Integrated Model

Intel, like Microsoft, had its fortunes made by IBM: eager to get the PC an increasingly vocal section of its customer base demanded out the door, the mainframe maker outsourced much of the technology to third party vendors, the most important being an operating system from Microsoft and a processor from Intel. The impact of the former decision was the formation of an entire ecosystem centered around MS-DOS, and eventually Windows, cementing Microsoft’s dominance.

Intel was a slightly different story; while an operating system was simply bits on a disk, and thus easily duplicated for all of the PCs IBM would go on to sell, a processor was a physical device that needed to be manufactured. To that end IBM insisted on having a “second source”, that is, a second non-Intel manufacturer for Intel’s chips. Intel chose AMD, and licensed first the 8086 and 8088 designs that were in the original IBM PC, and later, again under pressure from IBM, the 80286 design; the latter was particularly important because it was designed to be upward compatible with everything that followed.

This laid the groundwork for Intel’s strategy — and immense profitability — for the next 35 years. First off, the dominance of Intel’s x86 design was assured thanks to its integration with DOS/Windows: specifically, DOS/Windows created a two-sided market of developers and PC users, and DOS/Windows ran on x86.

However, thanks to its licensing deal with AMD, Intel wasn’t automatically entitled to all of the profits that would result from that integration; thus Intel doubled-down on an integration of its own: the design and manufacture of x86 chips. That is, Intel would invest huge sums of money into creating new and faster designs (the 386, the 486, the Pentium, etc.), and also invest huge sums of money into ever smaller and more efficient manufacturing processes that would push the limits of Moore’s Law. This one-two punch would ensure that, despite AMD’s license, Intel’s chips would be the only realistic choice for PC makers, allowing the company to capture the vast majority of the profits created by the x86’s integration with DOS/Windows.

Intel was largely successful. AMD did take the performance crown around the turn of the century with the Athlon 64, but the company was unable to keep up with Intel financially when it came to fabs, and Intel illegally leveraged its dominant position with OEMs to keep them buying mostly Intel parts; then, a few years later, Intel not only took back the performance lead with its Core architecture, but settled into the “tick-tock” strategy where it alternated new designs and new manufacturing processes on a regular schedule. The integration advantage was real.

TSMC’s Modular Approach

In the meantime there was a revolution brewing in Taiwan. In 1987, Morris Chang founded Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) promising “Integrity, commitment, innovation, and customer trust”. Integrity and customer trust referred to Chang’s commitment that TSMC would never compete with its customers with its own designs: the company would focus on nothing but manufacturing.

This was a completely novel idea: at that time all chip manufacturing was integrated a la Intel; the few firms that were only focused on chip design had to scrap for excess capacity at Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs) who were liable to steal designs and cut off production in favor of their own chips if demand rose. Now TSMC offered a much more attractive alternative, even if their manufacturing capabilities were behind.

In time, though, TSMC got better, in large part because it had no choice: soon its manufacturing capabilities were only one step behind industry standards, and within a decade had caught-up (although Intel remained ahead of everyone). Meanwhile, the fact that TSMC existed created the conditions for an explosion in “fabless” chip companies that focused on nothing but design. For example, in the late 1990s there was an explosion in companies focused on dedicated graphics chips: nearly all of them were manufactured by TSMC. And, all along, the increased business let TSMC invest even more in its manufacturing capabilities.

This represented into a three-pronged assault on Intel’s dominance:

- Many of those new fabless design companies were creating products that were direct alternatives to Intel chips for general purpose computing. The vast majority of these were based on the ARM architecture, but also AMD in 2008 spun off its fab operations (christened GlobalFoundries) and became a fabless designer of x86 chips.

- Specialized chips, designed by fabless design companies, were increasingly used for operations that had previously been the domain of general purpose processors. Graphics chips in particular were well-suited to machine learning, cryptocurrency mining, and other highly “embarrassingly parallel” operations; many of those applications have spawned specialized chips of their own. There are dedicated bitcoin chips, for example, or Google’s Tensor Processing Units: all are manufactured by TSMC.

- Meanwhile TSMC, joined by competitors like GlobalFoundries and Samsung, were investing ever more in new manufacturing processes, fueled by the revenue from the previous two factors in a virtuous cycle.

Intel’s Straitjacket

Intel, meanwhile, was hemmed in by its integrated approach. The first major miss was mobile: instead of simply manufacturing ARM chips for the iPhone the company presumed it could win by leveraging its manufacturing to create a more-efficient x86 chip; it was a decision that evinced too much knowledge of Intel’s margins and not nearly enough reflection on the importance of the integration between DOS/Windows and x86.

Intel took the same mistaken approach to non general-purpose processors, particularly graphics: the company’s Larrabee architecture was a graphics chip based on — you guessed it — x86; it was predicated on leveraging Intel’s integration, instead of actually meeting a market need. Once the project predictably failed Intel limped along with graphics that were barely passable for general purpose displays, and worthless for all of the new use cases that were emerging.

The latest crisis, though, is in design: AMD is genuinely innovating with its Ryzen processors (manufactured by both GlobalFoundries and TSMC), while Intel is still selling varations on Skylake, a three year-old design. Ashraf Eassa, with assistance from a since-deleted tweet from a former Intel engineer, explains what happened:

According to a tweet from ex-Intel engineer Francois Piednoel, the company had the opportunity to bring all-new processor technology designs to its currently shipping 14nm technology, but management decided against it.

my post was actually pointing out that market stalling is more troublesome than Ryzen, It is not a good news. 2 years ago, I said that ICL should be taken to 14nm++, everybody looked at me like I was the craziest guy on the block, it was just in case … well … now, they know

— François Piednoël (@FPiednoel) April 26, 2018

The problem in recent years is that Intel has been unable to bring its major new manufacturing technology, known as 10nm, into mass production. At the same time, the issues with 10nm seemed to catch Intel off-guard. So, by the time it became clear that 10nm wouldn’t go into production as planned, it was too late for Intel to do the work to bring one of the new processor designs that was originally developed to be built on the 10nm technology to its older 14nm technology…

What Piednoel is saying in the tweet I quoted above is that when management had the opportunity to start doing the work to bring their latest processor design, known as Ice Lake (abbreviated “ICL” in the tweet), [to the 14nm process] they decided against doing so. That was likely because management truly believed two years ago that Intel’s 10nm manufacturing technology would be ready for production today. Management bet incorrectly, and Intel’s product portfolio is set to suffer as a result.

To put it another way, Intel’s management did not break out of the integration mindset: design and manufacturing were assumed to be in lockstep forever.

Integration and Disruption

It is perhaps simpler to say that Intel, like Microsoft, has been disrupted. The company’s integrated model resulted in incredible margins for years, and every time there was the possibility of a change in approach Intel’s executives chose to keep those margins. In fact, Intel has followed the script of the disrupted even more than Microsoft: while the decline of the PC finally led to The End of Windows, Intel has spent the last several years propping up its earnings by focusing more and more on the high-end, selling Xeon processors to cloud providers. That approach was certainly good for quarterly earnings, but it meant the company was only deepening the hole it was in with regards to basically everything else. And now, most distressingly of all, the company looks to be on the verge of losing its performance advantage even in high-end applications.

This is all certainly on Krzanich, and his predecessor Paul Otellini. Then again, perhaps neither had a choice: what makes disruption so devastating is the fact that, absent a crisis, it is almost impossible to avoid. Managers are paid to leverage their advantages, not destroy them; to increase margins, not obliterate them. Culture more broadly is an organization’s greatest asset right up until it becomes a curse. To demand that Intel apologize for its integrated model is satisfying in 2018, but all too dismissive of the 35 years of success and profits that preceded it.

So it goes.