There is a fascinating paragraph in this Wall Street Journal article about Intel’s purchase of Mobileye NV,1 an Advanced Driver Assistance System primarily focused on camera-based collision avoidance and, going forward, autonomous driving:

The considerable premium Intel is willing to pay for Mobileye reflects the enormous value tech companies see in the automation of cars and trucks, said Mike Ramsay, research director at Gartner Inc. It would have been inconceivable a few years ago — it is more than double what the private-equity firm Cerberus Capital Management LLC paid for Chrysler LLC in 2007.

Chrysler LLC is, of course, a car manufacturer, since merged with Fiat; the price it was sold for is about as relevant to Mobileye as the value of a computer OEM to, well, Intel.

The Smiling Curve and PCs

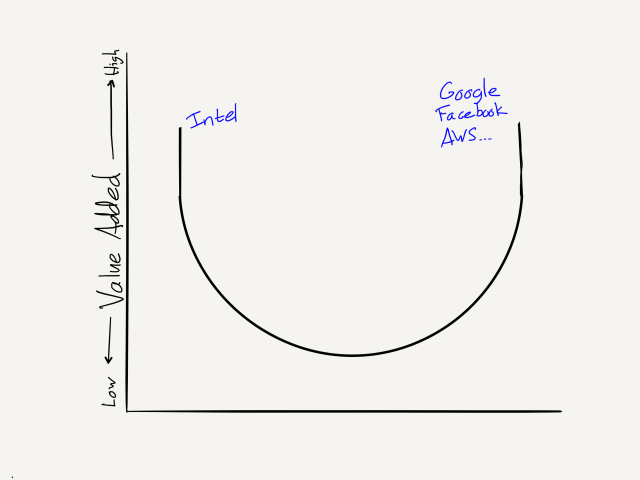

I wrote about The Smiling Curve back in 2014; it is a concept that was coined by one of those computer OEMs, Stan Shih of Acer, in the early 1990s, as a means of explaining why Acer needed to change its business model.

Shih explained the curve in his book Me-Too Is Not My Style:

The basic structure of the value-added curve, from left to right on the horizontal axis, are the upper, middle and down stream of an industry, that is, the component production, product assembly and distribution. The vertical axis represents the level of value-added. In terms of market competition type, the left side of the curve is worldwide competition whose success depends on technology, manufacturing and economy of scales. On the right side of the curve is regional competition. Its success depends on brand name, marketing channel and logistic capability.

Every industry has its own value-added curve. Different curves are derived according to different levels of value-added. The major factors in determining the level of value-added are entry barrier and accumulation of capability. In other words, with a higher entry barrier and greater accumulation of capabilities, the value-added will be higher.

Take the computer industry as an example. Microprocessor manufacturing or the establishment of brand name business comes with a higher entry barrier, and requires many years of strength accumulation to achieve progress. However, computer assembly is very easy. That is why no-brand computers are found everywhere in electronic shopping malls.

When Shih coined the concept in 1992, “microprocessor manufacturing” meant Intel: outside of the occasional challenge from AMD, Intel provided one of two parts (along with Windows) of the personal computer that couldn’t be bought elsewhere; the result was one of the most profitable companies of all time.

Note, though, that while a core piece of Intel’s competitive advantage (particularly relative to AMD) was, as Shih noted, the entry barrier of fabrication, Intel’s close connection to Windows — to software — was just as critical. It is operating systems that provide network effects and the tremendous profitability that follows, and operating systems are based on software. In other words, the PC smiling curve looked more like this:

Windows and x86 processors were effectively a bundle, and Microsoft and Intel split the profits. Remember, bundling is how you make money, and in this case Intel-based hardware provided Microsoft a vehicle to profit from licensing Windows, while Windows built an unassailable moat for both — at least in PCs.

The Smiling Curve and Phones

Obviously things went much differently for both Microsoft and Intel — and Acer — when it came to smartphones. The overall structure of the industry still fit the smiling curve, but the software was layered on completely differently:

Apple used software to bundle together manufacturing (done under contract) and the final product marketed to consumers; over time the company also added components, specifically microprocessors, to the bundle (also built under contract). The result was the most successful product of all time.

Google, meanwhile, made Android free; the bundle, such as there was, was between the operating system and Google’s cloud. The rest of the ecosystem was left to fight it out: distribution and marketing helped Samsung profit on the right, while R&D and manufacturing prowess meant profits for ARM, Samsung, and Qualcomm, along with a host of specialized component suppliers, on the left. Still, no one was as profitable as Intel was in the PC era, because no one had the software bundle.

That said, the role of software was critical: Intel, for example, started out the smartphone race at a performance disadvantage; while the company caught up the ecosystems had already moved on, because too much software was incompatible with x86.

The Smiling Curve and Servers

Intel has done better in the cloud:

The cloud took the commodification wave that hit PCs to a new extreme: major cloud providers, armed with massive scale and their own reference designs, hired Asian manufacturers directly. The one exception was Intel and its Xeon chips (which themselves undercut purpose-built server processors from companies like Sun and IBM), which continue to be the most important contributors to Intel’s bottom-line.2 Still, the real value in the cloud is on the right, where the software is: Facebook, Google, AWS.

Cars and the Future

A little over a year ago I explained in Cars and the Future that there were three changes happening in the personal transportation industry simultaneously:

- Drivetrains were changing from the internal combustion engine to electric

- Car operation was moving from human-based to computer-based (i.e. self-driving cars)

- Ownership was shifting from individuals to fleets, dispatched by ride-sharing services

As I noted in that piece each of these developments is in some respects independent of the other:

- Tesla has led the way in electric vehicles, building an amazing brand along the way, but traditional car companies are not far behind. That’s because the drivetrain is a sustaining technology, not a disruptive one: the business model is by and large the same.3

-

Multiple players are working on self-driving cars, including Mobileye; more on them (and Intel) in a bit. Other interested parties are Apple and Google, as well as the traditional car manufacturers — who also have rather mixed motivations. For now, limited self-driving functionality is a high-margin add-on; in the future, it could be their demise (more on this in a moment too)

-

Uber is the biggest player in ride-sharing, at least in most Western countries, although Lyft is lurking should Uber implode; Didi is dominant in China, while Southeast Asia has a number of smaller competitors. The ride-sharing business is a better one than many critics think; in developed markets rides are profitable on a unit basis, and there is negative churn: customers use the services more over time, not less. Competition is fierce, although the lowered customer acquisition costs of being the dominant player are under-appreciated, as well as the impact that has on drawing drivers.

What is interesting is that these three factors can be fit into the smiling curve framework:

This underscores the reality that all three are still very interconnected. More usefully, the smiling curve framework, particularly the lessons learned from the PC, smartphone, and server, also gives insight into how the transportation market may evolve, and explain why Intel made this purchase.

Car Manufacturers: The Bottom of the Smiling Curve

First, while the individual ownership model made it possible to bundle manufacturing and selling to end users (a la Apple in smartphones), said model doesn’t make sense going forward. The truth is that individual car ownership is a massive waste of resources, particularly for the individual: thousands of dollars are spent on an asset that is only used a single-digit percentage of the time and that depreciates rapidly (whether driven or not). The only reason we have such a model is that before the smartphone no other was possible (and the convenience factor of owning one’s own car was so great).

That, though, is no longer the case: in the future self-driving cars, owned and serviced by fleets, can be intelligently dispatched by ride-sharing services, resulting in utilization rates closer to 100% than to zero. Yes, humans will likely still move en masse in the morning and afternoon, but there will be packages and whatnot in the intervening time periods.

Moreover, self-driving cars will be built expressly for said utilization rates; yes, they will wear out, but a focus on longevity and serviceability over comfort and luxury will reduce manufacturers to commodity providers selling to bulk purchasers, not dissimilar to the companies building servers for today’s cloud giants.

That leaves the value for the ends.

Ride-Sharing Networks: The Right of the Smiling Curve

I’ve already written, both in Cars and the Future and Google, Uber, and the Evolution of Transportation-as-a-Service, that Uber’s position (again, barring implosion) is stronger than it seems. Yes, were, say, Waymo (Google’s self-driving car unit) able to instantly deploy self-driving cars at volume the ride-sharing company would be in big trouble, but in reality, even if Waymo decides to field a competitor, building routing capability (a related but still different problem than mapping) and, more importantly, gaining consumer traction will take time — time that Uber has to catch up in self-driving (certainly Waymo’s suit against Uber-acquisition Otto for stealing trade secrets looms large here; I’ll cover this more tomorrow).

The broader point, though, is that the winner (or winners) will look a lot like Uber looks today: most riders will use the same app, because whichever network has the most riders will be able to acquire the most cars, increasing liquidity and thus attracting more riders; indeed, the effects of Aggregation Theory will be even more pronounced when supply is completely commoditized per the point above.

Autonomous Driving Suppliers: The Left of the Smiling Curve

Remember, though, that while consumer-facing products and services get all of the attention, there is a lot of money to be made in components, particularly in an industry governed by the Smiling Curve. What is fascinating about this space is that it is an open question about which components will actually matter:

Hardware: For one, it’s not clear which sensing solution will prove superior: Mobileye’s camera-based approach (which Tesla, after ending its relationship with Mobileye after last year’s fatal car crash, is reproducing), or the Waymo-favored LIDAR approach (also used — allegedly stolen — by Uber). Perhaps it will be both.

Maps: Mapping is particularly critical for Waymo: its self-driving technology relies on super-detailed maps; if your objection is that producing said maps will be difficult, well, imagine telling yourself 15 years ago about Google Street View. Many car manufacturers, meanwhile, are increasingly casting their lot in with HERE, the former Nokia mapping unit (more on this in a moment as well).

Chips: Mobileye makes its own System-on-a-Chip called the EyeQ; selling a camera is meaningless without the capability of determining what is happening in the image. However, the EyeQ specifically and Mobileye generally cannot really compete with Nvidia, the real monster in this space. Nvidia realized a few years ago that its graphics capability, which emphasizes parallel processing, lends itself remarkably well to machine learning and neural network applications. Those, of course, are at the frontier of modern artificial intelligence research — including the sort of artificial intelligence necessary to drive cars. That is why Nvidia’s PX2 chip is in Tesla’s newest vehicles, along with those from a host of other manufacturers.

The real open question is software: Google is writing its own, Apple is apparently writing its own, Tesla is writing its own, Uber is writing its own, and Mobileye is writing its own. The car companies? It’s a mixed bag — and fair to question how good they’ll be at it.

Intel + Mobileye

This is the context for Intel’s acquisition. First off, yes, it is ridiculously expensive. The purchase price of $14.71 billion (once you back out Mobileye’s cash-on-hand) equates to an EBITDA multiple of 118; it helps that Intel is paying with overseas cash, which the company hasn’t paid taxes on. And second, I’ve long argued that society would be better off if companies would simply milk their company-defining products and return the cash to shareholders to invest in new up-and-comers (with the caveat that Intel had one of the greatest pivots of all-time, from memory to microprocessors).

That said, there is a lot to like about this deal for Intel (from Mobileye’s perspective, accepting a 34% premium is a no-brainer). Obviously Intel has chip expertise (although its graphics division lags far behind Nvidia’s); with Mobileye the company adds hardware expertise. It goes deeper than that though: Mobileye and Intel have actually been working together already, with HERE.

In fact, that is understating the situation: Intel bought a 15% ownership stake in HERE earlier this year, and Intel and Mobileye made a deal with BMW last year to build a self-driving car. In short, Intel is assembling the pieces to be a real player in autonomous cars: hardware, maps, chips, software, and strong relationships with car manufacturers.

Indeed, with this acquisition Intel’s greatest strength and greatest weakness is its dominant position with established manufactures: there is the outline of a grand alliance between car manufacturers, HERE maps, and Intel/Mobileye; the only hang-up is that the future of transportation is one in which the car manufacturers are the biggest losers. Companies like Uber or Google, meanwhile, have nothing to lose (well, Uber does, but they seem to grasp the threat).

Regardless, it’s a worthwhile bet for Intel: the company seems determined to not repeat its mistakes in smartphones, and given that the structure of self-driving cars looks more like servers than anything else, it’s a worthwhile space to splurge in.

What a great name. Seriously! ↩

Yes, there continues to be noise about ARM in the data center, most recently Microsoft’s announced commitment to use ARM in its data centers; for now Intel is dominant, and it will take more than a vaporware announcement to change that ↩

Although it should be noted that Teslas are not sold through dealerships ↩