Apple did what needed to be done to get that unfortunate iPad ad out of the news; you know, the one that somehow found the crushing of musical instruments and bottles of paint to be inspirational:

The ad was released as a part of the company’s iPad event, and was originally scheduled to run on TV; Tor Myhren, Apple’s vice-president of marketing communications, told AdAge:

Creativity is in our DNA at Apple, and it’s incredibly important to us to design products that empower creatives all over the world…Our goal is to always celebrate the myriad of ways users express themselves and bring their ideas to life through iPad. We missed the mark with this video, and we’re sorry.

The apology comes across as heartfelt — accentuated by the fact that an Apple executive put his name to it — but I disagree with Myhren: the reason why people reacted so strongly to the ad is that it couldn’t have hit the mark more squarely.

Aggregation Theory

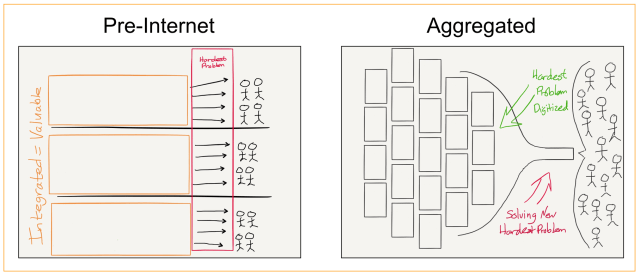

The Internet, birthed as it was in the idealism of California tech in the latter parts of the 20th century, was expected to be a force for decentralization; one of the central conceits of this blog has been to explain why reality has been so different. From 2015’s Aggregation Theory:

The fundamental disruption of the Internet has been to turn this dynamic on its head. First, the Internet has made distribution (of digital goods) free, neutralizing the advantage that pre-Internet distributors leveraged to integrate with suppliers. Secondly, the Internet has made transaction costs zero, making it viable for a distributor to integrate forward with end users/consumers at scale.

This has fundamentally changed the plane of competition: no longer do distributors compete based upon exclusive supplier relationships, with consumers/users an afterthought. Instead, suppliers can be commoditized leaving consumers/users as a first order priority. By extension, this means that the most important factor determining success is the user experience: the best distributors/aggregators/market-makers win by providing the best experience, which earns them the most consumers/users, which attracts the most suppliers, which enhances the user experience in a virtuous cycle.

In short, the analog world was defined by scarcity, which meant distribution of scarce goods was the locus of power; the digital world is defined by abundance, which means discovery of what you actually want to see is the locus of power. The result is that consumers have access to anything, which is to say that nothing is special; everything has been flattened.

- Google broke down every publication in the world into individual pages; search results didn’t deliver you to the front page of a newspaper or magazine, but rather dropped you onto individual articles.

- Facebook promoted user-generated content to the same level of the hierarchy as articles from professional publications; your feed might have a picture of your niece followed by a link to a deeply-reported investigative report followed by a meme.

- Amazon created the “Everything Store” with practically every item on Earth and the capability to deliver it to your doorstep; instead of running errands you could simply check out.

- Netflix transformed “What’s on?” to “What do you want to watch?”. Everything from high-brow movies to budget flicks to prestige TV to reality TV was on equal footing, ready to be streamed whenever and wherever you wanted.

- Sites like Expedia and Booking changed travel from an adventure mediated by a travel agent or long-standing brands to search results organized by price and amenities.

Moreover, this was only v1; it turns out that the flattening can go even further:

- LLMs are breaking down all written text ever into massive models that don’t even bother with pages: they simply give you the answer.

- TikTok disabused Meta of the notion that your relationships were a useful constraint on the content you wanted to see; now all short-form video apps surface content from across the entire network based on their understanding of what you individually are interested in.

- Amazon is transforming into a logistics powerhouse befitting the fact that Amazon.com is increasingly dominated by 3rd-party merchant sales, and extending that capability throughout the economy.

- All of Hollywood, convinced that content was what mattered, jointly killed the linear TV model to ensure that all professionally-produced content was available on-demand, even as YouTube became the biggest streamer of all with user-generated content that is delivered through the exact same distribution channel (apps on a smart device) as the biggest blockbusters.

- Services like Uber and Airbnb commoditized transportation and lodging to the individual driver or homeowner.

Apple is absent from this list, although the App Store has had an Aggregator effect on developers; the reason the company belongs, though, and why they were the only company that could make an ad that so perfectly captures this great flattening, is because they created the device on which all of these services operate. The prerequisite to the commoditization of everything is access to anything, thanks to the smartphone. “There’s an app for that” indeed:

This is what I mean when I say that Apple’s iPad ad hit the mark: the reason why I think the ad resonated so deeply is that it captured something deep in the gestalt that actually has very little to do with trumpets or guitars or bottles of paint; rather, thanks to the Internet — particularly the smartphone-denominated Internet — everything is an app.

The Bicycle for the Mind

The more tangible way to see in which that iPad ad hit the mark it to play it in reverse:

Hey @Apple, I fixed it for you (sound on) pic.twitter.com/OwVnYNgXhT

— Reza Sixo Safai (@rezawrecktion) May 8, 2024

This is without question the message that Apple was going for: this one device, thin as can be, contains musical instruments, an artist’s studio, an arcade machine, and more. It brings relationships without borders to life, complete with cute emoji. And that’s not wrong!

Indeed, it harkens back to one of Steve Jobs’ last keynotes, when he introduced the iPad 2. My favorite moment in that keynote — one of my favorite Steve Jobs’ keynote moments ever, in fact — was the introduction of GarageBand. You can watch the entire introduction and demo, but the part that stands out in my memory is Jobs — clearly sick, in retrospect — moved by what the company had just produced:

I’m blown away with this stuff. Playing your own instruments, or using the smart instruments, anyone can make music now, in something that’s this thick and weighs 1.3 pounds. It’s unbelievable. GarageBand for iPad. Great set of features — again, this is no toy. This is something you can really use for real work. This is something that, I cannot tell you, how many hours teenagers are going to spend making music with this, and teaching themselves about music with this.

Jobs wasn’t wrong: global hits have originated on GarageBand, and undoubtedly many more hours of (mostly terrible, if my personal experience is any indication) amateur experimentation. Why I think this demo was so personally meaningful for Jobs, though, is that not only was GarageBand about music, one of his deepest passions, but it was also a manifestation of his life’s work: creating a bicycle for the mind.

I remember reading an Article when I was about 12 years old, I think it might have been in Scientific American, where they measured the efficiency of locomotion for all these species on planet earth. How many kilocalories did they expend to get from point A to point B, and the condor won: it came in at the top of the list, surpassed everything else. And humans came in about a third of the way down the list, which was not such a great showing for the crown of creation.

But somebody there had the imagination to test the efficiency of a human riding a bicycle. Human riding a bicycle blew away the condor, all the way off the top of the list. And it made a really big impression on me that we humans are tool builders, and that we can fashion tools that amplify these inherent abilities that we have to spectacular magnitudes, and so for me a computer has always been a bicycle of the mind, something that takes us far beyond our inherent abilities.

I think we’re just at the early stages of this tool, very early stages, and we’ve come only a very short distance, and it’s still in its formation, but already we’ve seen enormous changes, but I think that’s nothing compared to what’s coming in the next 100 years.

In Jobs’ view of the world, teenagers the world over are potential musicians, who might not be able to afford a piano or guitar or trumpet; if, though, they can get an iPad — now even thinner and lighter! — they can have access to everything they need. In this view “There’s an app for that” is profoundly empowering.

After the Flattening

The duality of Apple’s ad speaks to the reality of technology: its impact is structural, and amoral. When I first started Stratechery I wrote a piece called Friction:

If there is a single phrase that describes the effect of the Internet, it is the elimination of friction. With the loss of friction, there is necessarily the loss of everything built on friction, including value, privacy, and livelihoods. And that’s only three examples! The Internet is pulling out the foundations of nearly every institution and social more that our society is built upon.

Count me with those who believe the Internet is on par with the industrial revolution, the full impact of which stretched over centuries. And it wasn’t all good. Like today, the industrial revolution included a period of time that saw many lose their jobs and a massive surge in inequality. It also lifted millions of others out of sustenance farming. Then again, it also propagated slavery, particularly in North America. The industrial revolution led to new monetary systems, and it created robber barons. Modern democracies sprouted from the industrial revolution, and so did fascism and communism. The quality of life of millions and millions was unimaginably improved, and millions and millions died in two unimaginably terrible wars.

Change is guaranteed, but the type of change is not; never is that more true than today. See, friction makes everything harder, both the good we can do, but also the unimaginably terrible. In our zeal to reduce friction and our eagerness to celebrate the good, we ought not lose sight of the potential bad.

Today that exhortation might run in the opposite direction: in our angst about the removal of specialness and our eagerness to criticize the bad, we ought not lose sight of the potential good.

Start with this site that you are reading: yes, the Internet commoditized content that was previously granted value by virtue of being bundled with a light manufacturing business (i.e. printing presses and delivery trucks), but it also created the opportunity for entirely new kinds of content predicated on reaching niche audiences that are only sustainable when the entire world is your market.

The same principle applies to every other form of content, from music to video to books to art; the extent to which being “special” meant being scarce is the extent to which the existence of “special” meant a constriction of opportunity. Moreover, that opportunity is not a function of privilege but rather consumer demand: the old powers may decry that their content is competing with everyone on the Internet, but they are only losing to the extent that consumers actually prefer to read or watch or listen to something else. Is this supposed to be a bad thing?

Moreover, this is just as much a feather in Apple’s cap as the commoditization of everything is a black mark: Apple creates devices — tools — that let everyone be a creator. Indeed, that is why the ad works in both directions: the flattening of everything means there has been a loss; the flattening of everything also means there is entirely new opportunity.

The AI Choice

One thing I do credit Apple for is not trying to erase the ad from the Internet — it’s still posted on CEO Tim Cook’s X account — because I think it’s important not just as a marker of what has happened over the last several years, but also the choices facing us in the years ahead.

The last time I referenced Steve Jobs’ “Bicycle of the Mind” analogy was in 2018’s Tech’s Two Philosophies, where I contrasted Google and Facebook on one side, and Microsoft and Apple on the other: the former wanted to create products that did things for you; the latter products that let you do more things. This was a simplified characterization, to be sure, but, as I noted in that Article, it was also related to their traditional positions as Aggregators and platforms, respectively.

What is increasingly clear, though, is that Jobs’ prediction that future changes would be even more profound raise questions about the “bicycle for the mind” analogy itself: specifically, will AI be a bicycle that we control, or an unstoppable train to destinations unknown? To put it in the same terms as the ad, will human will and initiative be flattened, or expanded?

The route to the former seems clear, and maybe even the default: this is a world where a small number of entities “own” AI, and we use it — or are used by it — on their terms. This is the outcome being pushed by those obsessed with “safety”, and demanding regulation and reporting; that those advocates also seem to have a stake in today’s leading models seems strangely ignored.

The alternative — MKBHDs For Everything — means openness and commoditization. Yes, those words have downsides: they mean that the powers that be are not special, and sometimes that is something we lament, as I noted at the beginning of this Article. Our alternative, though, is not the gatekept world of the 20th century — we can’t go backwards — but one where the flattening is not the elimination of vitality but the tilling of the ground so that something — many things — new can be created.