When Spotify filed for its direct listing in 2018, it was popular to compare the streaming music service to Netflix, the streaming video service; after all, both were quickly growing subscription-based services that gave consumers media on demand. This comparison was intended as a bullish one for Spotify, given that Netflix’s stock had increased by 1,113% over the preceding five years:

The problem with the comparison is that Spotify clearly was a different kind of business than Netflix, thanks to its very different relationship to its content providers; whereas Netflix had always acquired content on a wholesale basis — first through licensing deals with content owners, and later by making its own content — Spotify licensed content on a revenue share basis. This latter point is why I was skeptical of Spotify’s profit-making potential; I wrote at the time in Lessons From Spotify, in a section entitled Spotify’s Missing Profit Potential:

That, though, is precisely the problem: Spotify’s margins are completely at the mercy of the record labels, and even after the rate change, the company is not just unprofitable, its losses are growing, at least in absolute euro terms:

Moreover, it seems highly unlikely Spotify’s Cost of Revenue will improve much in the short-term: those record deals are locked in until at least next year, and they include “most-favored nation” provisions, which means that Spotify has to get Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, and Merlin (the representative for many independent labels), which own 85% of the music on Spotify as measured by streams, to all agree to reduce rates collectively. Making matters worse, the U.S. Copyright Royalty Board just increased the amount to be paid out to songwriters; Spotify said the change isn’t material, but it certainly isn’t in the right direction either.

I compared this (unfavorably) to Netflix in a follow-up:

Netflix has licensed content, not agreed-to royalty agreements. That means that Netflix’s costs are fixed, which is exactly the sort of cost structure you want if you are a growing Internet company. Spotify, on the other hand, pays the labels according to a formula that has revenue as the variable, which means that Spotify’s marginal costs rise in-line with their top-line revenue.

Both companies proceeded to do quite well in the markets over the next three-and-a-half years, with a decided edge to Netflix; however, the last six months undid all of those gains, with Netflix getting hit harder than Spotify:

Setting aside any analysis of absolute value, I think the relative trend is justified: I still maintain, as I did in 2018, that Spotify and Netflix are fundamentally different businesses because of their relationship to content; now, though, I think that Spotify’s position is preferable to Netflix, and has more long-term upside. Moreover, I don’t think this is a new development: I was wrong in 2018 to prefer Netflix to Spotify; worse, I should have already known why.

Categorizing Aggregators

In my original article about Aggregation Theory I wrote:

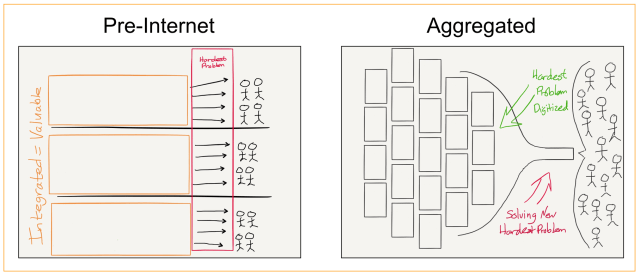

The value chain for any given consumer market is divided into three parts: suppliers, distributors, and consumers/users. The best way to make outsize profits in any of these markets is to either gain a horizontal monopoly in one of the three parts or to integrate two of the parts such that you have a competitive advantage in delivering a vertical solution. In the pre-Internet era the latter depended on controlling distribution…

The fundamental disruption of the Internet has been to turn this dynamic on its head. First, the Internet has made distribution (of digital goods) free, neutralizing the advantage that pre-Internet distributors leveraged to integrate with suppliers. Secondly, the Internet has made transaction costs zero, making it viable for a distributor to integrate forward with end users/consumers at scale.

This has fundamentally changed the plane of competition: no longer do distributors compete based upon exclusive supplier relationships, with consumers/users an afterthought. Instead, suppliers can be commoditized leaving consumers/users as a first order priority. By extension, this means that the most important factor determining success is the user experience: the best distributors/aggregators/market-makers win by providing the best experience, which earns them the most consumers/users, which attracts the most suppliers, which enhances the user experience in a virtuous cycle.

Fast forward to 2017, where in Defining Aggregators I sought to provide a more specific definition of an Aggregator; specifically, Aggregators had:

- A direct relationship with users

- Zero marginal costs for serving users

- Demand-driven multi-sided networks with decreasing acquisition costs

The rest of the post was devoted to building a taxonomy of Aggregators based on their relationships to suppliers:

- Level 1 Aggregators paid for supply, but had superior buying power due to their user base; Netflix was here.

- Level 2 Aggregators incurred marginal transaction costs for adding supply; “real-world” companies like Uber and Airbnb were here.

- Level 3 Aggregators had zero supply costs; Google and Facebook were here.

Notice the tension between the two articles, specifically this sentence in Aggregation Theory: “no longer do distributors compete based upon exclusive supplier relationships”. Had I kept that sentence in mind then I ought to have concluded that Level 1 and Level 2 were not Aggregators at all: sure, companies in these categories could scale on the demand side, but they were going to hit a wall on the supply side. Indeed, this has been a problem for Uber in particular: the company has never been able to escape from the need to compete for supply, which is another way of saying the company has never been able to make any money.

Netflix has a similar problem: the company’s content investments have failed to provide the evergreen lift in customer acquisition I anticipated; despite having more original content than ever, Netflix has hit the wall in terms of subscriber growth, particularly in developed countries where it can charge the highest prices. While some of these challenges were forseeable — I predicted that Netflix would have a rough stretch where all of its once-content providers tried their hand at streaming1 — it does seem likely that Netflix is going to struggle to get significantly more leverage on its content costs than it has to date, as that is the only way to not just acquire but also keep its subscribers.

In short, Defining Aggregator was focused on the demand-side in its definition and the supply-side in its taxonomy; my original

Article — and, in retrospect, the better one — did the opposite. The only way you can truly control demand — the tell-tale sign of an Aggregator — is to have fully commoditized and infinitely scalable supply; streaming video fails on the former, and ride-sharing on the latter.

Spotify and Commoditized Supply

With that in mind, go back to the reason I was skeptical of Spotify, and those revenue-sharing deals with record labels. In 2017’s The Great Unbundling I noted that the music industry, much to the surprise of anyone who observed the Napster era, had ended up in pretty good shape:

While piracy drove the music labels into the arms of Apple, which unbundled the album into the song, streaming has rewarded the integration of back catalogs and new music with bundle economics: more and more users are willing to pay $10/month for access to everything, significantly increasing the average revenue per customer. The result is an industry that looks remarkably similar to the pre-Internet era:

Notice how little power Spotify and Apple Music have; neither has a sufficient user base to attract suppliers (artists) based on pure economics, in part because they don’t have access to back catalogs. Unlike newspapers, music labels built an integration that transcends distribution.

It’s easy to see why this would be a bad thing for Spotify; on the flipside, you can see why many of the most optimistic assumptions about Spotify’s upside rested on the company somehow eliminating the labels completely, even though the fact that new music immediately becomes back catalog music means that the label’s relative position in the music value chain is quite stable. This is why I’ve always been skeptical about the possibility of Spotify displacing the labels entirely, and the short-lived exclusive wars confirmed that point of view: it’s better for artists and labels for all music to be available everywhere.

My contention — and the key insight undergirding this Article — is that this is better for Spotify, as well. Go back to the point about commoditization: an input does not need to be free to be commoditized. Sure, the marginal cost of streaming music — which is nothing but bits — is zero; it is a credit to the music labels’ new-music-to-back-catalog flywheel that they are able to charge for access to these bits. At the same time, the bits are available to anyone for roughly the same price: that is why not just Spotify and Apple, but also YouTube, Amazon, Tidal, Deezer, etc. all have roughly the same catalog for roughly the same price. Streaming music isn’t free, but it is an infinitely available non-exclusive commodity.

Look again at the contrast to the other companies I highlighted above: there are a limited number of potential ride-share drivers, which means that Uber has to compete with Lyft with a never-ending set of driver incentives that make profitability difficult if not impossible to achieve; Netflix has some of the content — not all of it — and it has to bid against competitors to get more of it.

This does, to be clear, make it easier to achieve a direct profit: as I noted above, because Netflix pays a fixed cost for content it can earn a surplus without having to pay anything extra to the content producer, whereas Spotify can only eke out profitability from its subscribers by reducing its operational costs. The real opportunity for an Aggregator, though, is building a business model that is independent of supply and instead predicated on owning demand. Here Spotify is better placed than Netflix — although the latter is finally making moves in that direction.

Spotify’s Investor Day

Earlier this month Spotify had an investor day (which I covered in an Update last week); Charlie Hellman, vice president and head of music product, presented a textbook case as to why Spotify is an Aggregator for music, with the business model to match. Hellman started by emphasizing Spotify’s role in new music discovery:

It’s important to remember that first and foremost Spotify is a music company. All of our music team’s strategies ladder up to two primary goals: making a unique and superior music experience for fans, and creating a more open and valuable ecosystem for artists. These two goals really complement one another, which is clear to see when you look at the playlisting ecosystem we’ve spent the last decadee defining and perfecting. Whatever your mood, your style, whatever the occassion, Spotify has something for you, and as Gustav mentioned, Spotify drives around 22 billion discoveries a month. On top of that, 1/3 of all new artist discoveries happen on personalized algorithmic playlists. Listeners love this exposure to new music, as well as the personalized touch. Discovery is our bread and butter, and it’s driving a level of engagement that no streaming service can claim.

This is the number one characteristic of an Aggregator: in a world of scarcity distribution was the most valuable; in a world of abundance it is discovery that matters most. To that end, Hellman emphasized that the world of digital music was one of ever-increasing abundance, thanks in part to Spotify:

The music industry is changing fast. There have never been fewer barriers to entry, and that’s enabling more and more talented artists to be discovered…but with this reduction in barriers comes an increase in the number of artists seeking success. We’re in the midst of an explosion in creativity where tens of thousands of songs are uploaded each day, and that rate of daily uploads has doubled in the last two years. In this rapidly growing landscape, artists need an evolving toolkit that works for the millions who will make up tomorrow’s music industry. One that mirrors their creativity and ambition by offering speed and scale.

Hellman highlighted free tools Spotify offers, including analytics, custom art and videos, and the ability to pitch your song for a playlist. What is far more important from a business perspective, though, is the fact you can pay for promotion.

In addition to these free tools, we’ve also invested in building the most performant and effective commercial tools for promotion in the streaming era. Because there’s so much being added to Spotify every day, artists need tools that will help them stand out, now more than ever, and we’re uniqely positioned to deliver effective promotion for artists for a few reasons. First, unlike like, say, social media marketing, our promotion tools reach people that have already actively made a decision to open Spotify and listen to music. It’s contextual. Plus, our ability to target listeners based on their listening activity, their taste, is second to none. And further, we have the unique ability to actually report back how many people listened to or saved the music as a result. Our ability to deliver the best promotional opportunities for artists presents a tremendous opportunity.

This is an opportunity that is paying off; CFO Paul Vogel explained how Spotify’s heavy investments in podcasting (more on this in a moment) were obscuring major improvements in the financial performance of the company’s music business:

Our music business has been a real source of strength, driving strong revenue growth, and strong margin expansion. This may not be immediately evident in our consolidated results, but make no mistake, we have delivered against the expectations and framework we rolled out at the time of our direct listing. Isolating just the performance of our music operations, you’d see that our music revenues, which consist of premium subscriptions, ad-supported music, our marketplace suite of artist tools, and strategic licensing, great at a 24% compound annual growth rate, in-line with our expectations on an FX-neutral basis, and importantly, our music gross margins have increased over the same time frame, reaching 28.3% in 2021. This is approximately 150-basis points higher than our total 2021 consolidated margin of 26.8%…Looking at our progression in another way, since 2018, the last year before our major podcast investment, our music margins have expanded on average by approximately 75 basis points per year. At our last investor day we told you to expect gross margins in the 30-35% range over the long-term. This was, and still remains, the goal for our music operations. As you can see from these numbers, we are clearly on our way.

Let me unpack how we have expanded our music gross margins. At the beginning of 2018, we announced the development of our marketplace business — all of the tools and services that Charlie described earlier. Our thesis back then was that by providing increased value to artists, creators, and labels, they would see material benefit, and so would Spotify, and that is exactly what we are seeing today. We’ve long maintained that our success is not solely tied to renegotiating new headline rates. It’s about our ability to innovate, right along with our partners, to grow a business that benefits both artists and Spotify, and that’s what we’ve done with Marketplace. In 2018 our Marketplace contribution to gross profit was only $20 million. In 2021 it grew to $160 million, 8x the size in just four years. We expect that number to increase another 30% or more in 2022. We see tremendous upside in Marketplace, and anticipate that it’s financial contribution will continue to grow at a healthy double-digit rate in the years ahead. Marketplace is the quintessential example of our approach to capital allocation. There was a significant up-front cost to build-and-launch these offerings, but we saw compelling data which gave us the confidence to double-down and invest aggressively against our goals. It may have taken time to build up momentum, but our patience and conviction has paid off, and we are seeing material benefit from our investment.

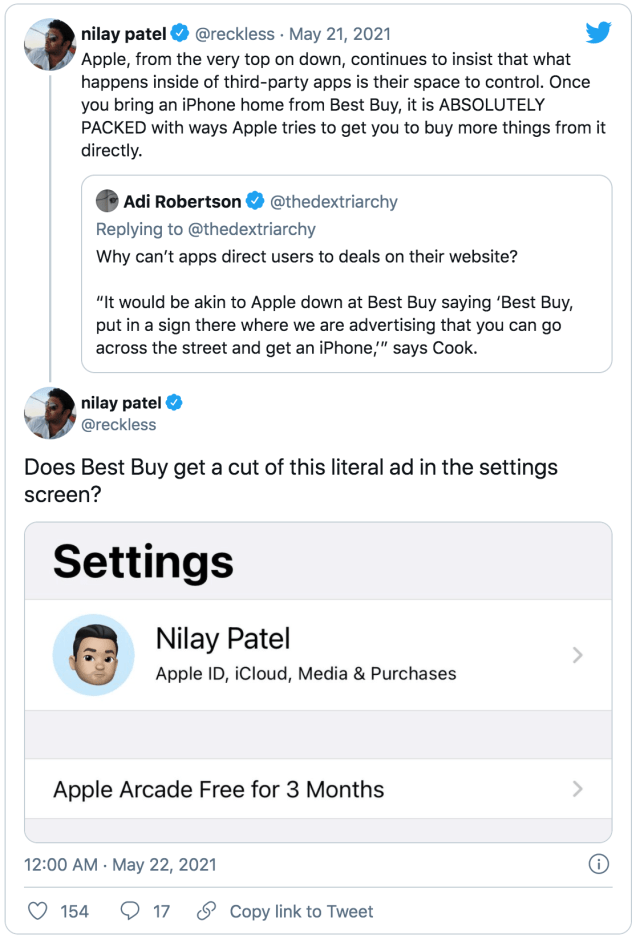

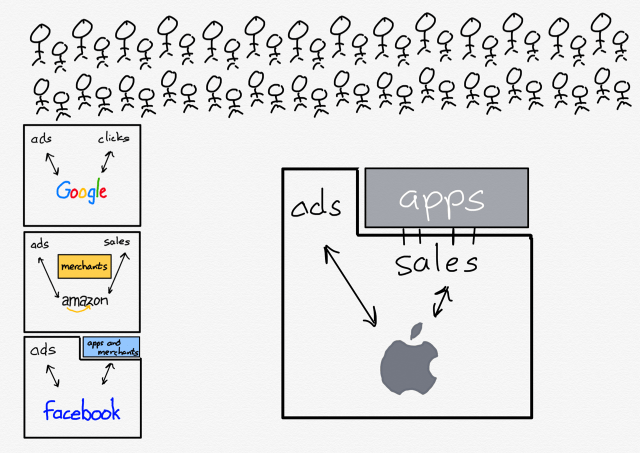

Notice how this business — in its mechanics, if not its financial numbers — looks more like a Google or a Facebook than a Netflix: Spotify isn’t earning money by making margin on its content spend; rather, it is seeking to enable more content than ever, confident that it controls the best means to surface the content users want. Those means can then be sold to the highest bidder, with all of the margin going to Spotify. Spotify calls this promotion — it certainly looks a lot like the old radio model of pay-to-play — but that’s really just another word for advertising. Moreover, this isn’t Spotify’s only advertising business: the company has long been building an ad-supported music business, and is now heavily investing in doing the same for podcasting (which has always clearly been an aggregation strategy).

Acting Like an Aggregator

Being an Aggregator is not the only way to make money; indeed, it is amongst the most difficult. It is far more straightforward to make a differentiated product and charge for it; that is also the only possibility for most products and companies. What makes Aggregators unique is that they are best served by doing the opposite of what is optimal for traditional businessess:

- Instead of having differentiated content, Aggregators want commoditized content, and more of it.

- Instead of increasing margin on their users, Aggregators want to reduce it, ideally to zero, or at least to the same level as their competitors (as in the case of Spotify).

- Instead of introducing friction in the market, the better to lock-in users, Aggregators want to decrease friction, confident the gravitational pull of their user experience will, all things being equal, draw in more users than their competitors, increasing their attractivness to not just suppliers but also advertisers (who, in the case of Spotify’s music business, may be the same entities).

Spotify has, for the most part, acted like an Aggregator: the company has fought exclusives in the music business, kept its subscription prices as low as possible, and in the case of podcasts ensured its Anchor platform supports all podcast players.2 Netflix has not: the company has invested heavily in its own content, steadily increases its prices, and is now embarking on a campaign to make sure its best customers pay more for sharing access.

What is noteworthy are the exceptions: on Spotify’s side the most obvious one are its podcast exclusives. The potential payoff in terms of taking podcast share is obvious; being an Aggregator means being the biggest player in a particular space, and by all accounts Spotify’s strategy has delivered exactly that. There are, though, risks in the approach: exclusive content creators are liable to become ever more expensive over time as they seek to seize their share of the value they create. Moreover, they risk triggering a response by competitors making their own exclusive deals. To put it in the terms discussed above, exclusive content is de-commoditized content, and that is bad for Aggregators (that noted, Spotify’s biggest long-term competitor is not Apple but YouTube, a formidable Aggregator in its own right; maybe exclusives aren’t the worst idea).

Netflix, meanwhile, is finally building — or contracting to build — an ad business. While this still seems like a reaction to slowing growth instead of a considered strategy, what is important is the shift from selling exclusive supply to selling exclusive demand: the latter is far more scalable and defensible, although the transition will be very dificult (and may not fully pay off if Netflix isn’t willing to invest on its own).

The takeaway I am most interested in, though, is a selfish one: I had an essential part of Aggregation Theory — the commoditzation of supply — right originally, only to forget that insight and make several bad calls along the way. In the case of Netflix and Spotify I was right in observing that they were different businesses; my mistake was mislabeling which had more potential as an Aggregator.

I wrote a follow-up to this Article in this Daily Update.

What I got wrong about my prediction was the timing, thanks to COVID. ↩

Spotify has also ensured that independent podcasters like Stratechery can deliver their content on Spotify. ↩

![A human basking in the sun of AGI utopia]](https://i0.wp.com/stratechery.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/dall-e-2.png?resize=640%2C640&ssl=1)