Senator Elizabeth Warren deserves credit: I have been writing about antitrust, particularly in the context of Aggregation Theory, for years, but the most concrete proposal I have put forward is that social networks should not be allowed to acquire other social networks. Senator Warren, on the other hand, last week presented a far more wide-reaching proposal that specifically targeted Facebook, Google, and Amazon:

Today’s big tech companies have too much power — too much power over our economy, our society, and our democracy. They’ve bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit, and tilted the playing field against everyone else. And in the process, they have hurt small businesses and stifled innovation.

I want a government that makes sure everybody — even the biggest and most powerful companies in America — plays by the rules. And I want to make sure that the next generation of great American tech companies can flourish. To do that, we need to stop this generation of big tech companies from throwing around their political power to shape the rules in their favor and throwing around their economic power to snuff out or buy up every potential competitor.

That’s why my administration will make big, structural changes to the tech sector to promote more competition — including breaking up Amazon, Facebook, and Google.

Senator Warren added Apple in an interview at SXSW with The Verge:

There was one company that fits that description that you did not mention.

Apple. They’re in.

You want to break up Apple as well.

Yep.

You were very specific about how you’d break up Google and the rest. How would you break up Apple?

Apple, you’ve got to break it apart from their App Store. It’s got to be one or the other. Either they run the platform or they play in the store. They don’t get to do both at the same time. So it’s the same notion.

Unfortunately, Senator Warren’s proposal helps highlight why I have not gone further with my own: hers would create massive new problems, have significant unintended consequences, and worst of all, not even address the issues Senator Warren is concerned about (with one possible exception I will get to in a moment). Worst, it would do so by running roughshod over the idea of judicial independence, invite endless lawsuits and bureaucratic meddling around subjective definitions, and effectively punish consumers for choosing the best option for them. Mike Masnick at TechDirt gets into many of these problems, and concludes:

This entire plan gets headlines (duh) because so many people are (perhaps reasonably!) angry at the power of big tech companies. But, very little in the actual plan makes much sense. The “platform utility” idea will lead to massive, wasteful, stupid lawsuits. The unwinding of old mergers will involve interfering with an independent agency, and seem unlikely to do much to change the main “concerns” that Senator Warren raises in the first place.

And, again, none of this is to say we shouldn’t be concerned about big internet companies with too much power. It’s a perfectly reasonable concern, but just because you want to “do something” and “this is something,” doesn’t mean that it’s the something we should do.

I do know what is the first thing Senator Warren should do: rectify three clear areas where I believe she is mistaken about technology. Her proposal is wrong about tech’s history, the source of the tech giants’ power, and the fundamental nature of technology itself. All three are, unsurprisingly, interrelated, and it is impossible to craft a cogent antitrust policy without getting all of them right.

History: Microsoft and Google

Senator Warren opens the article by crediting the Microsoft antitrust case for the emergence of Google and Facebook:

Twenty-five years ago, Facebook, Google, and Amazon didn’t exist. Now they are among the most valuable and well-known companies in the world. It’s a great story — but also one that highlights why the government must break up monopolies and promote competitive markets.

In the 1990s, Microsoft — the tech giant of its time — was trying to parlay its dominance in computer operating systems into dominance in the new area of web browsing. The federal government sued Microsoft for violating anti-monopoly laws and eventually reached a settlement. The government’s antitrust case against Microsoft helped clear a path for Internet companies like Google and Facebook to emerge.

The story demonstrates why promoting competition is so important: it allows new, groundbreaking companies to grow and thrive — which pushes everyone in the marketplace to offer better products and services. Aren’t we all glad that now we have the option of using Google instead of being stuck with Bing?

Start with the most obvious error: Bing was not even launched until 2009, eight years after the Microsoft case was settled. MSN Search, its predecessor, did launch in 1998, but with licensed search results from Inktomi and AltaVista; Microsoft didn’t launch its own web crawler until 2005 (these details will matter in a moment).

What is more striking is that, in retrospect, the core piece of the government’s case doesn’t make any sense: of course a browser should be bundled with an operating system; a new computer without a browser would be practically useless (for one, how do you install a browser?). Moreover, Apple, not without merit, argues that restricting rendering engines to the one that ships with the OS (all browsers on iOS have no choice but to use the built-in rendering engine) has significant security benefits; this is debatable, but ultimately, most don’t care, simply because browsers are means to information, not ends.

This, crucially, is something Microsoft did not understand in the 1990s; Microsoft’s operating system monopoly was predicated on owning the APIs with which applications were built, creating both lock-in and an ever expanding network effect. Unsurprisingly, Microsoft viewed the web through this exact same lens; that meant that Netscape was a threat because it was “middleware”, a potential means to run applications that were not locked into Windows. This is true, by the way — web apps work across operating systems and browsers — but this fact has absolutely nothing to do with the rise of Google. After all, when Google IPO’d in 2004, Internet Explorer had 95% market share; a browser was a means, not an end.

The reality is that Google is an operating system of sorts, but the system is not a PC but rather the entire web; what ties things together are not APIs, but links. And, crucially, the business model that makes sense is not licensing, but advertising. This is a value chain that never even occurred to Microsoft, and why would it? The entire company was predicated on controlling operating systems for physical computers, controlling the APIs on top, and earning revenue through licensing; it was fabulously profitable, and as history shows again and again, being fabulously profitable with an existing value chain is the best way to not only fail to recognize a new market opportunity (Microsoft didn’t even have a web crawler until after Google’s IPO!), but to in fact be at a massive disadvantage when you finally do so.

Look no further than mobile: Microsoft was not encumbered by antitrust when it came to their mobile ambitions, and yet they failed even more spectacularly there than they did online. In this case the company didn’t “miss” the opportunity — Windows Mobile came out back in 2000 — it was just stuck in a PC mindset when it came to product development, attached to its Windows licensing model when it came to monetization, and institutionally incapable of producing superior end user experiences thanks to the company’s traditional focus on platforms and compatibility.

In short, to cite Microsoft as a reason for antitrust action against Google in particular is to get history completely wrong: Google would have emerged with or without antitrust action against Microsoft; if anything the real question is whether or not Google’s emergence shows that the Microsoft lawsuit was a waste of time and money.1

Power: Google and Aggregation Theory

Senator Warren’s second mistake is a misstating of why large tech companies are dominant. She writes:

America’s big tech companies have achieved their level of dominance in part based on two strategies:

Using Mergers to Limit Competition. Facebook has purchased potential competitors Instagram and WhatsApp. Amazon has used its immense market power to force smaller competitors like Diapers.com to sell at a discounted rate. Google has snapped up the mapping company Waze and the ad company DoubleClick. Rather than blocking these transactions for their negative long-term effects on competition and innovation, government regulators have waved them through.

Using Proprietary Marketplaces to Limit Competition. Many big tech companies own a marketplace — where buyers and sellers transact — while also participating on the marketplace. This can create a conflict of interest that undermines competition. Amazon crushes small companies by copying the goods they sell on the Amazon Marketplace and then selling its own branded version. Google allegedly snuffed out a competing small search engine by demoting its content on its search algorithm, and it has favored its own restaurant ratings over those of Yelp.

The merger issue is a real one, but only when it comes to propagating power; Facebook was dominant before it bought Instagram and WhatsApp, Google before it bought DoubleClick or YouTube, and Amazon before it bought Diapers.com or Whole Foods (I do share Senator Warren’s concern about acquisitions; I will return to this point). Notably, Apple has not made any major acquisitions other than Beats headphones, and that too came well after the company had created the iPhone.

Similarly, the conflict of interest Senator Warren worries about is also post-dominance; none of Google, Facebook, Amazon, nor Apple achieved their power by “using proprietary marketplaces to limit competition”. That is not to say this, like acquisitions, isn’t a worthwhile issue, but it is flat out wrong to say that these are the reasons “big tech companies achieved their level of dominance.”

Then again, perhaps it is best for Senator Warren’s argument that her article never does explain how these companies became so big, because the reason cuts at the core of her argument: Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple dominate because consumers like them. Each of them leveraged technology to solve a unique user needs, acquired users, then leveraged those users to attract suppliers onto their platforms by choice, which attracted more users, creating a virtuous cycle that I have christened Aggregation Theory. Specifically:

- Google solved search, which attracted users; Google’s supply (web pages), thanks to the fundamental nature of the web, were already effectively “on Google”, but even then web pages have worked diligently to deliver content in a way that Google expects. Why? Because users start at Google — demand is what matters.

- Facebook digitized offline relationships, which attracted users, which were both consumers and suppliers of content; professional content creators followed, not only linking to their content on Facebook but creating content specifically tailored for Facebook’s audience, making Facebook that much more attractive for users. Again, what mattered was demand, not supply.

- Amazon leveraged the Internet to achieve a dominant strategy of offering superior selection and the lowest price, starting with books. This gained Amazon customers, which gave the company leverage to bring on first other media like CDs and DVDs, which gained them more users, and later goods of all types; Amazon then launched the Amazon Marketplace, through which suppliers could come onto Amazon directly. Why? Because that is where demand was.

- Apple defined the modern smartphone, gaining users who were blown away by Apple’s first-party apps; that attracted app developers, who were soon clamoring for access to iPhone users. Apple closed that loop by creating the App Store, which attracted more users, which attracted more developers, etc. Critically, though, the users came first; one of Microsoft’s many mobile mistakes was believing it could effectively “buy” a supply of apps and thus earn users, but that doesn’t work in a world where owning demand matters most.

Aggregation Theory is the reason why all of these companies have escaped antitrust scrutiny to date in the U.S.: here antitrust law rests on the consumer welfare standard, and the entire reason why these companies succeed is because they deliver consumer benefit.

The European Union does have a different standard, rooted in a drive to preserve competition; given that the virtuous cycle described by Aggregation Theory does tend towards winner-take-all effects, it is not a surprise that Google in particular has faced multiple antitrust actions from the European Commission. Even the EU standard, though, struggles with the real consumer benefits delivered by Aggregators.

Consider the Google Shopping case: Google was found guilty of antitrust violations in a case brought by a shopping comparison site called Foundem, which complained about their site being buried when consumers were searching for items to buy. This complaint made no sense, as I explained in Ends, Means, and Antitrust:

If I search for a specific product, why would I not want to be shown that specific product? It frankly seems bizarre to argue that I would prefer to see links to shopping comparison sites; if that is what I wanted I would search for “Shopping Comparison Sites”, a request that Google is more than happy to fulfill:

The European Commission is effectively arguing that Google is wrong by virtue of fulfilling my search request explicitly; apparently they should read my mind and serve up an answer (a shopping comparison site) that is in fact different from what I am requesting (a product)?

There is certainly an argument to be made that Google, not only in Shopping but also in verticals like local search, is choking off the websites on which Search relies by increasingly offering its own results. At the same time, there is absolutely nothing stopping customers from visiting those websites directly, or downloading their apps, bypassing Google completely. That consumers choose not to is not because Google is somehow restricting them — that is impossible! — but because they don’t want to. Is it really the purview of regulators to correct consumer choices willingly made?

As I noted above, there are some important points made here by Senator Warren; at a fundamental level, though, any sort of antitrust proposal that does not seriously grapple with the reality that the power of these companies flows from controlling demand — that is, consumer choice, willingly made — not from controlling supply, like monopolies of old, is going to be fundamentally flawed.

Nature: What is Tech?

This mistake by Senator Warren only came into focus with that interview where she included Apple as a target for her proposal. Here’s more from that interview:

Pulling that apart, the App Store is the method by which Apple keeps the iPhone secure. It’s integrated into the platform. How would you propose that Apple and Google distribute apps if they don’t run the store?

Well, are they in competition with others who are developing the products? That’s the problem all the way through this, and it’s what you have to keep looking for. If you run a platform where others come to sell, then you don’t get to sell your own items on the platform because you have two comparative advantages. One, you’ve sucked up information about every buyer and every seller before you’ve made a decision about what you’re going to sell. And second, you have the capacity — because you run the platform — to prefer your product over anyone else’s product. It gives an enormous comparative advantage to the platform.

This would not be the first time in US history that this kind of arrangement had to be broken up. Back when the railroads were dominant, and you had to get steel or wheat onto the railroad, there was a period of time when the railroads figured out that they could make money not only by selling tickets on the railroad, but also by buying the steel company and then cutting the price of transporting steel for their own company and raising the price of transporting steel for any competitors. And that’s how the giant grows.

The problem is that’s not competition. That’s just using market dominance, not because they had a better product or because they were somehow more customer-friendly or in a better place. It’s just using market dominance. So my principle is exactly the same: what was applied to railroad companies more than a hundred years ago, we need to now look at those tech platforms the same way.

This is pretty explicitly taking Senator Warren’s critique of Amazon in particular and applying it to Apple, and to be fair, it is not completely without merit: Apple has quite clearly leveraged the fact it owns the platform to compete with Spotify, for example, and has definitely suppressed competition when it comes to built-in apps like Mail and the aforementioned Safari.

At the same time, do consumers not matter at all here? Is Senator Warren seriously proposing that smartphone be sold with no apps at all? Was Apple breaking the law when they shipped the first iPhone with only first-party apps? At what point did delivering an acceptable consumer experience out-of-the-box cross the line into abusing a dominant position? This argument may make sense in theory but it makes zero sense in reality.

What is even more striking, though, is that the App Store does have a massive antitrust problem: it is not Apple unfairly competing with app developers, it is Apple unfairly imposing massive complexity and extracting 30% of revenue with its contractual requirement, enforced by App Review, that developers use Apple’s payment mechanism. I wrote about this extensively last year in Antitrust, the App Store, and Apple (also see this follow-up); I think there is a case Apple’s policies would be found anticompetitive under a Quick Look review, and may even be a per se antitrust tying violation.

The important takeaway for this Article, though, is the degree to which Senator Warren missed the point: there is significant consumer benefit both to having preinstalled apps and also to Apple controlling the installation of apps. There is a big benefit to suppliers (app developers) as well: the app market on PCs died in large part due to security concerns, which Apple obviated with the App Store to the tremendous benefit of every participant in the ecosystem. Senator Warren’s proposal would make the App Store worse for everyone.

That leads to a broader point: “tech” is not simply another category, like railroads or telecom. Tech is a means, not an end, but Senator Warren’s approach presumes the latter. That is why she proposes the same set of rules for the sale of toasters and the sale of apps, and everything in between. The truth is that Amazon is a retailer; Apple a combination of hardware maker and platform makers. Google is a search and advertising company, and Facebook a publishing and advertising company. They all have different value chains and different ways of impacting competition, both fairly and unfairly, and to fail to appreciate just how different they are is a great way to make bad laws that not only fail to fix problems but also create entirely new ones.

That is not to say there aren’t genuine concerns about the biggest tech companies; I was absolutely genuine when I stated at the beginning that Senator Warren deserves credit for bringing these issues to the forefront. To my mind there are three major issues that deserve antitrust attention:

Issue 1: Digital Advertising

Senator Warren expresses concern in her article about kill zones when it comes to new startups:

Weak antitrust enforcement has led to a dramatic reduction in competition and innovation in the tech sector. Venture capitalists are now hesitant to fund new startups to compete with these big tech companies because it’s so easy for the big companies to either snap up growing competitors or drive them out of business. The number of tech startups has slumped, there are fewer high-growth young firms typical of the tech industry, and first financing rounds for tech startups have declined 22% since 2012.

This is decidedly not the case when it comes to enterprise-focused startups: that sector is thriving with all kinds of new businesses being created, acquired, and going public. The problem is the consumer Internet, which is to say that the problem is digital advertising. As I explained last year, both Google and Facebook are Data Factories; writing about Facebook specifically:

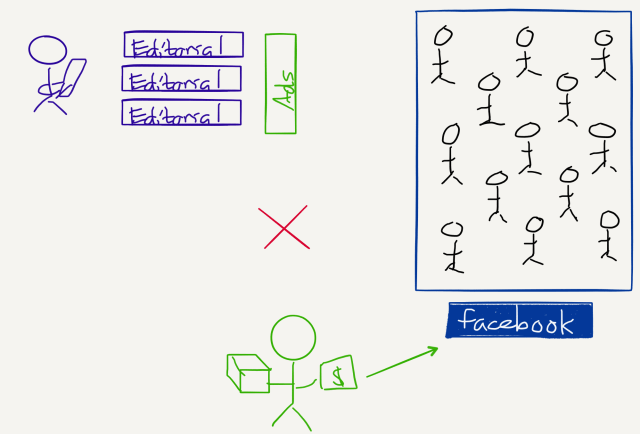

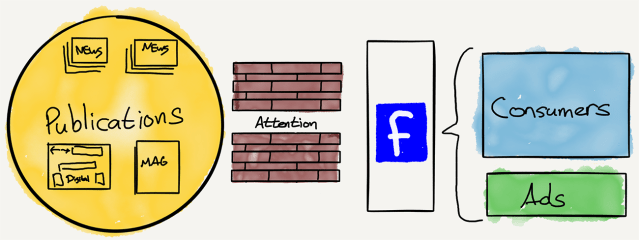

Facebook quite clearly isn’t an industrial site (although it operates multiple data centers with lots of buildings and machinery), but it most certainly processes data from its raw form to something uniquely valuable both to Facebook’s products (and by extension its users and content suppliers) and also advertisers (and again, all of this analysis applies to Google as well):

- Users are better able to connect with others, find content they are interested in, form groups and manage events, etc., thanks to Facebook’s data.

- Content providers are able to reach far more readers than they would on their own, most of whom would not even be aware those content providers exist, much less visit of their own volition.

- Advertisers are able to maximize the return on their advertising dollar by only showing ads to individuals they believe are predisposed to like their product, making it more viable than ever before to target niches (to the benefit of their customers as well).

And then, in exchange for these benefits that derive from data, Facebook sucks in data from all three entities:

- Users provide Facebook with data directly, both through information and media they upload, and also through their actions on Facebook properties.

- Content is not simply data in its own right, but also a catalyst for generating user action data.

- Advertisers, like content providers, not only provide data in its own right, which acts as a catalyst for generating user action data, but also upload huge amounts of data directly in order to better target prospective customers.

The end result is that Facebook and Google are far more valuable to advertisers than anyone else: they offer the most efficient spend when it comes to a return on advertising, and thanks to their ability to reach practically everyone, combined with the infinite nature of digital content, require the lowest investment. Put plainly, the ROI on Google and Facebook digital advertising is unmatched, and the chasm is only growing.

This is a tremendous problem for any would-be consumer Internet company, particular any product that depends on a network effect. The single most important feature when it comes to building a large user base and a leverage-able network effect is that the product be free-to-use, which means the only viable business model is advertising. As I just noted, though, the only place that advertisers want to be — for good reason! — is Google or Facebook. Ergo, consumer Internet companies are increasingly difficult to get started.

Snap is an unfortunate example of this reality: Snapchat is a clear demonstration that it is possible to build a competing social network in a world dominated by Facebook; unfortunately, it also appears to be an example of how is is even more difficult to build a profitable advertising business.

I don’t have a clear solution to this problem; if anything, privacy-focused regulation like GDPR are only exacerbating the issue, given that Google and Facebook acquire most user data on their platforms. Any solution that seeks to actually make a positive impact on competition, though, has to start with advertising.

Issue 2: Acquisitions

As I’ve hinted at a couple of times in this article, this is where I do mostly agree with Senator Warren. The truth is that Snapchat would have been a far greater threat to Facebook had the latter not been allowed to acquire Instagram. In a Daily Update last year I explored an alternate history where Instagram stayed independent:

This is where it is critical to consider the entire ecosystem. Had Instagram continued as a standalone company I do believe it would have been successful in building out an advertising business; it just would have taken a lot more time and effort…What is more important, though, is that an independent Instagram would have been the best possible thing that could have happened to Snapchat. The fundamental problem facing Snapchat is that it wasn’t enough for the company to have higher usage or deeper engagement with teens and young adults, demographic groups advertisers are desperate to reach. As long as Instagram was using Facebook’s ad infrastructure, it would always be more cost effective to reach those groups using Facebook’s ad engine.

This is why I have called Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram The Greatest Regulatory Failure of the Past Decade, and called for an end to social networks being allowed to buy other social networks. I do have qualms about the idea of retroactively undoing deals, but I do think Senator Warren is directionally correct in this case.

More broadly, as I explained in The Value Chain Constraint, the price of being an Aggregator is tuning your company to the value chain within which you compete; it follows that all of these companies will face significant challenges moving into new spaces with new value chains. To that end, what makes the most sense from a management perspective is leveraging the tremendous amounts of cash thrown off by their core businesses to acquire and invest in companies competing in different value chains.

On the flipside, to the extent regulators wish to constrain Aggregators, the single most effective lever is limiting acquisitions. There are significant problems with this, to be sure, particularly when it comes to the incentives for new company creation (most successful exits are acquisitions, not IPOs), but at least this is a remedy that is somewhat approaching the problem.

Issue 3: Contracts

As I have detailed, Aggregators already have massive structural advantages in their value chains; to that end, there should be significantly more attention paid to market restrictions that are enforced by contracts.

Go back to Microsoft: in my estimation the most egregious antitrust violations committed by Microsoft were the restrictions placed on OEMs, both to ensure the installation of Internet Explorer as well as to suppress alternative operating systems. These were not violations rooted in market dominance, at least not directly, but rather contracts that OEMs could not afford to say ‘No’ to.

This is an area where the European Commission has gotten it right with regard to Google: as a condition of access to Google apps, most critically the Play Store, OEMs were prohibited from selling any phones with Android forks. This is a restriction on competition produced not by market dominance, at least not directly, but rather contracts that OEMs could not afford to say ‘No’ to.

This is also the issue with Apple’s App Store: the restriction on linking to a website for purchasing an ebook or subscribing to a streaming service is not rooted in any sort of technical limitation; rather, it is an arbitrary rule in the App Developer Agreement enforced by Apple’s App Review team. It has nothing to do with consumer security, and everything to do with Apple’s bottom line.

This is an area ripe for enhanced antitrust enforcement: these large tech companies have enough advantages, most of them earned through delivering what customers want, and abetted by the fundamental nature of zero marginal costs. Seeking to augment those advantages through contracts that suppliers can’t say ‘No’ to should be viewed with extreme skepticism.

Let me reiterate a point I have made twice now: I appreciate Senator Warren raising these issues; they are indeed critical not only for the world today, but also the world we wish to create in the future. That, though, only increases the importance of getting things right: the history, the fundamental problem, and the nature of tech. Only then can we start to grope for solutions that actually make the situation better rather than worse.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

It appears that Senator Warren’s argument is based on a New York Times Magazine piece entitled The Case Against Google; I refuted the article directly in this Daily Update. It’s worth repeating a few additional points:

- First, Microsoft executives blaming antitrust oversight for their failure to compete with Google is self-serving of the highest order. It is a ready-made excuse for the company missing out on search — but as I noted, it doesn’t explain mobile. The reality is far more prosaic: Microsoft didn’t have the structure or culture to compete in either; to CEO Satya Nadella’s credit the company has realized this and is now focused on being an enterprise platform.

- Second, as I noted above, Microsoft’s Google competitor was woefully inadequate; Google was so much better — and only a click away — that setting the default to MSN Search made no difference.

- Third, there are far-fetched arguments that Microsoft could have somehow made Google inaccessible on Internet Explorer. Beyond the fact that this would only work with a transparent black list (unlike applications, Microsoft couldn’t play any tricks with APIs), such a block would be easily circumvented by…downloading another browser! Indeed, this would have been the surest route for Netscape to survive.

In short, while there are arguments to be made about the impact of the antitrust decision on the emergence of web apps — which again, was Microsoft’s core concern — it has nothing to do with the emergence of Google, which was not only not competitive with Microsoft but not even on the company’s radar at the time of the antitrust case. ↩